New release Lamb is considered by some to be the latest in a line of arthouse-style horror films that have been categorized as “elevated horror” by some critics and bloggers.

No-one seems to agree quite what elevated horror is or if it’s even new at all, except that the genre has at last come out of the shadows to reach mainstream audiences.

But even that suggestion is contentious. The Exorcist was the first horror to land a Best Film Oscar nod. The Omen was the biggest grossing film of 1976. The Shining has been reassessed as a classic. Scream reinvented the slasher pic for a new generation spawning sequels and, arguably, for the current teen-friendly hits too like It, Stranger Things and Netflix’s Fear Street series.

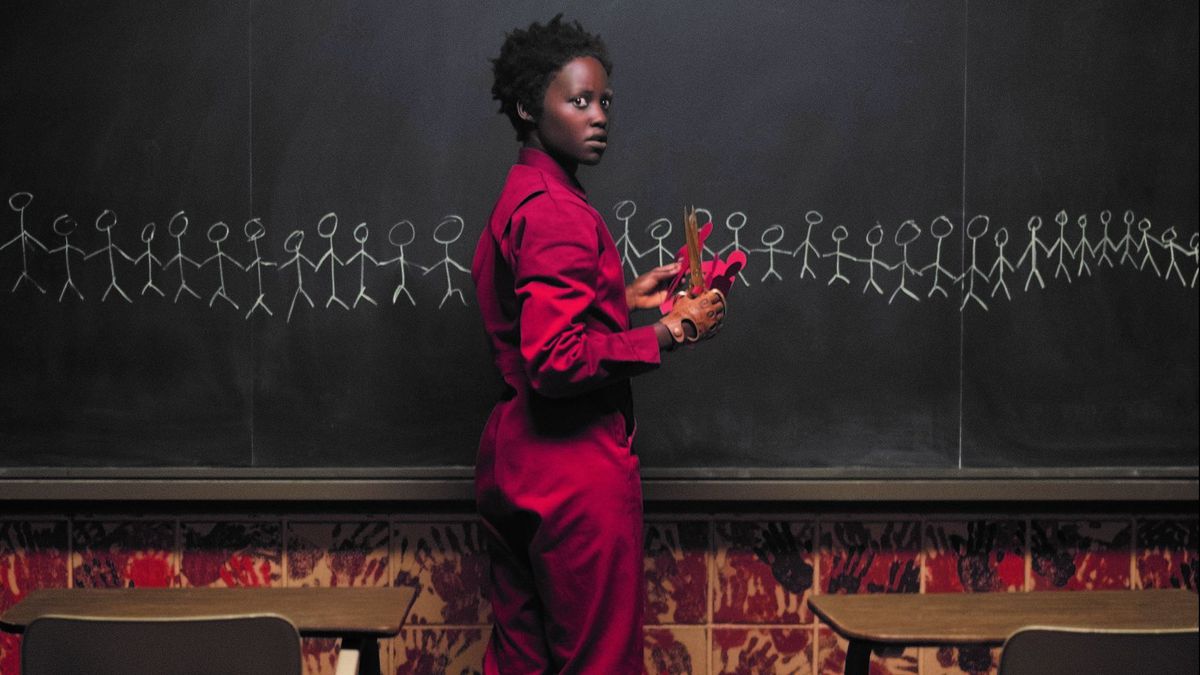

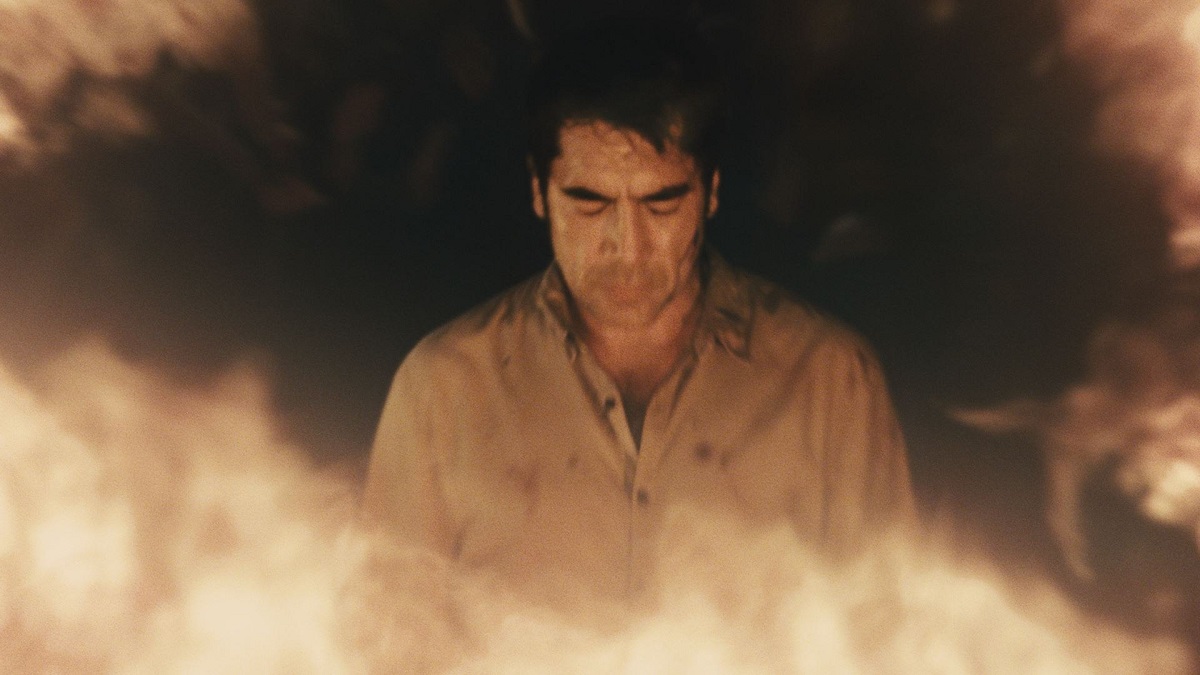

It’s said that examples of so-called “elevated horror” contain social commentary. They feature classic horror genre motifs within an arthouse feature film style. Examples include The Witch, Hereditary, Get Out, Us, Midsommar, The Babadook, and mother!

Yet the idea that a horror film can smuggle social critique into its corpus is nothing new. The 1968 zombie picture Night of the Living Dead is a civil rights analog. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre can be seen as a black comedy on American values. Cannibal Holocaust (while reactionary in its depiction of women and rape in particular) can be read as satirizing white western media’s exploitation of ethnic groups.

More recently, The Purge and its sequels are making a clear critique of contemporary politics — but this doesn’t fall under the badge of elevated horror because it is doing so without arthouse trappings.

The Beat suggests films like Lamb, The Witch, and Hereditary “have cemented this new style of arthouse horror as a genre unto itself.” Perhaps this is because they are directed by auteurs from outside the mainstream such as Valdimar Jóhannsson, Robert Eggers, and Ari Aster.

Yet Italian filmmaker Dario Argento was producing the very definition of arthouse horror in the 1970s with films like Four Flies on Grey Velvet and Suspiria. The highly stylized aesthetic was influential on recent arthouse horror fare including Amer (2009) from Belgium duo Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzan, Peter Strickland’s In Fabric, Luca Guadagnino’s 2018 Suspiria remake, and Edgar Wright’s forthcoming Last Night in Soho.

READ MORE: Lamb: Arthouse Horror and the Rise of a New Genre (The Beat)

If many of these are style of substance, then elevated horror means not just arthouse sensibility but also social critique and the production value designed for commercial success.

Vanity Fair credits production companies Blumhouse and A24 in particular for giving indie filmmakers the budget (modest, but not small) and a creatively free reign to talk about social issues such as diversity and class using the vehicle of horror.

“Clever marketing had its part to play in all of this as well; after the generally uninspired horror of the 2000s, horror’s image had hit a low point. And both Blumhouse and A24 both had a hand in turning that ship around… . Studios large and small took notice and began to do the same, backing away from gimmicks and instead investing in visionary talent.”

READ MORE: This Was the Decade Horror Got “Elevated” (Vanity Fair)

Hollywood took notice too, bumping up South Korean foreign language film Parasite to last year’s best picture winner.

The truth is, the horror genre — like the sci-fi genre — has always been used as a means to reflect and comment on the human condition.

The Horror Writers Association’s president, John Palisano, sums this up best in an interview with the Los Angeles Times. “Horror is speaking to all generations in a way it never has before. In the 1950s, it gave people a way to deal with atomic fears; in the ‘60s, horror addressed societal change; again in the ‘70s, with consumerism, and the ‘80s, with AIDS. Now, the entire country is unified in a threat we’ve never had to face before: the threat from within. And it speaks to both sides [of the political divide].”