Black and white as an aesthetic choice in this day and age is generally still a badge of the arthouse film and an artifice not lost on Academy voters, who nominated Roma and Cold War in 2018 and Mank in 2020.

This year, they’ll likely have more to judge with films as varied as The French Dispatch and Being the Ricardos employing several black-and-white sequences, while Passing, Belfast and The Tragedy of Macbeth being shot almost entirely without color. In TV, even the opening scenes to WandaVision were in black and white, which may have confused younger viewers into adjusting their set.

Like WandaVision, this current crop are all period movies that use the old-fashioned format to evoke a bygone era, but even C’mon C’mon, which takes place in contemporary times and has Joaquin Phoenix as a radio journalist crisscrossing the country with his nephew, was filmed in monochrome.

To understand why everyone is going grayscale, The New York Times talked to the cinematographers behind three of the season’s most striking black-and-white features.

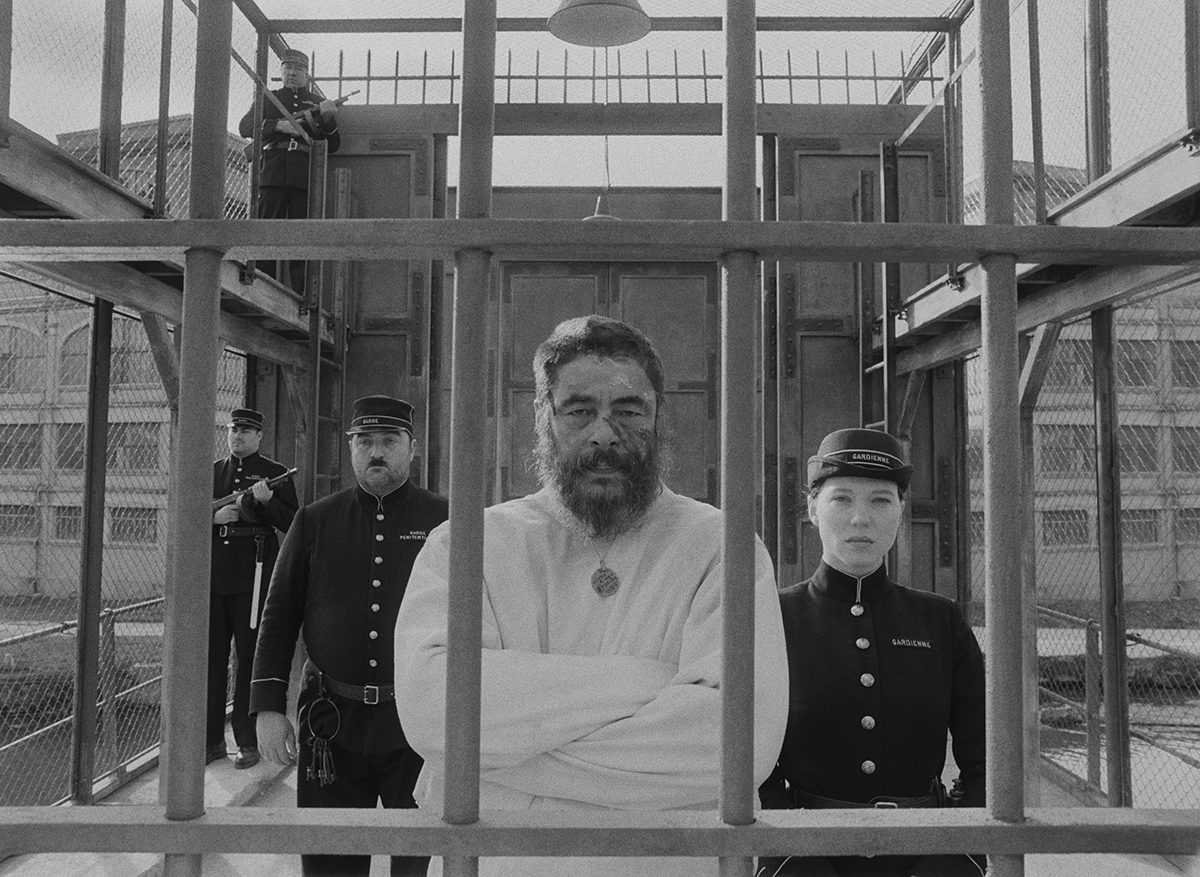

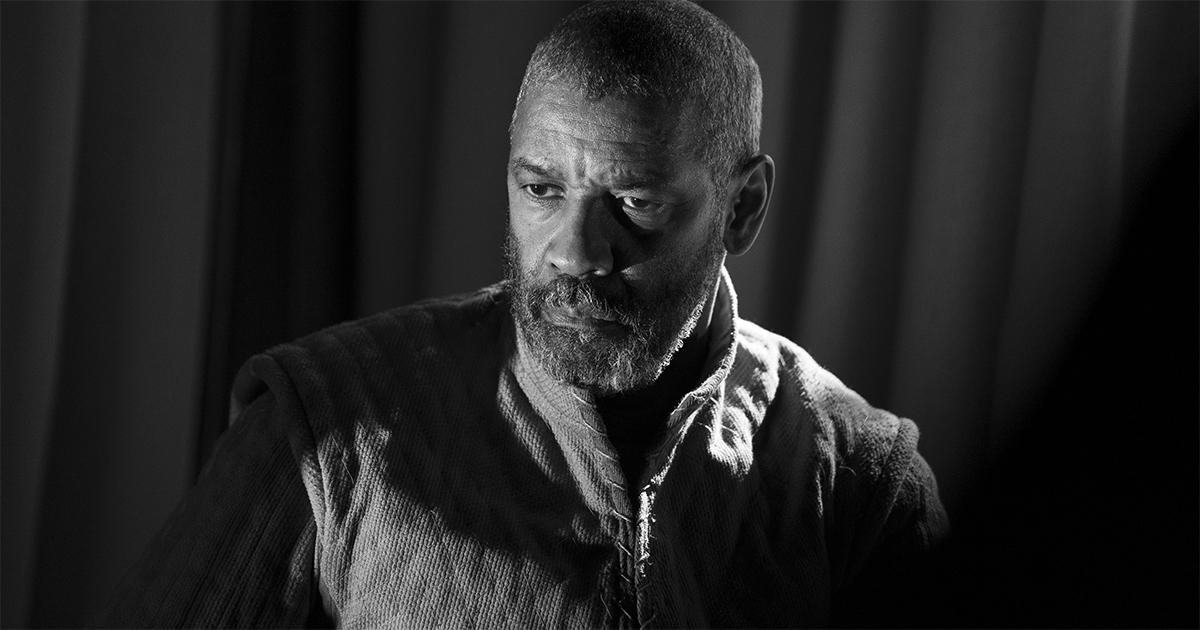

The Tragedy of Macbeth

For his new spin on Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the director Joel Coen wanted to strip the play down to its barest essence. The result is a fast and ruthless reimagining leached of all color, shot in a claustrophobic 4:3 aspect ratio.

“It’s meant to bring theatricality, and to lose temporality,” cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel said. “It’s not about the 1700s, and it’s not about Scotland, either. We’re giving an abstraction, but a very creative one.”

All that austerity makes a striking visual impression, but Delbonnel said it was simply in service of the play’s language. The same creative rules applied to the actors Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand who must rely on body language and delivery not scenery or props.

Though this Macbeth was made in the spirit of minimalism, Delbonnel often brought in the boldest lights he could muster.

“The whole movie is lit with theater light, like you’d see at a Beyoncé concert, which has very, very hard shadows,” he said. “In color, it would be unbearable, but in black-and-white, it looks amazing.”

Passing

Based on the 1929 novel by Nella Larsen, Passing is about two light-skinned Black women: Irene (Tessa Thompson), a well-respected but restless doctor’s wife, and Clare (Ruth Negga), her childhood friend who has been passing for white. A chance meeting in a hotel tearoom reunites the two after years spent apart, and cinematographer Eduard Grau chose to flood that initial encounter with a striking amount of white light.

“This is the brightest I’ve ever done a scene in my life,” Grau said. “You don’t see that a lot, especially in dramas, to have such a bright scene without a lot of detail in the whites. It also came from the fact that we didn’t want to clearly show to the audience at first whether our characters were white or Black or mixed race. Everything is so bright that it’s difficult to tell.”

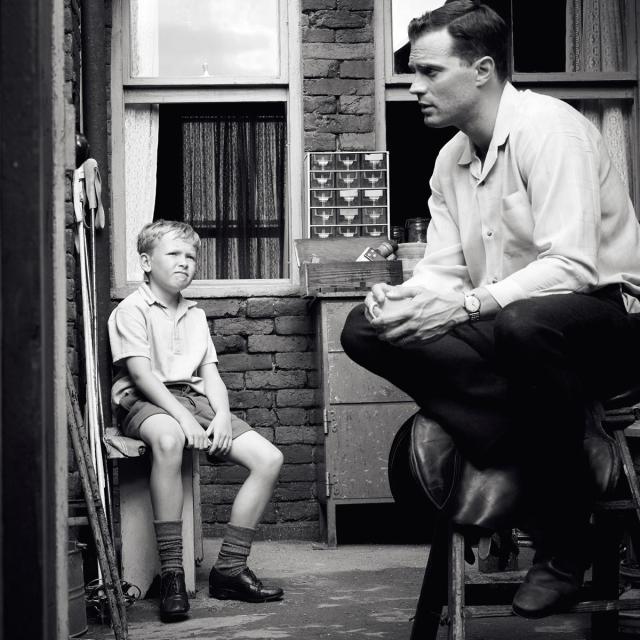

Belfast

Kenneth Branagh’s first feature as director, Dead Again, used black and white as a mechanism to differentiate the story’s flashback sequences. He’s also used black and white, again as a flashback, in the opening to next year’s glossy big screen adaptation of Death on the Nile. Before then though he’s written and directed Belfast, loosely based on his own upbringing in the city.

“There is something really lucid and clear and at the same time ethereal and mysterious inherent in black-and-white photography,” cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos, BSC told NAB Amplify. “I feel color is often better at being descriptive — you can see it’s autumn because of the red leaves in shot. But since filmmaking tends to be about narrowing the focus for the audience, about how and where they see things, black-and-white is a fantastic way of capturing emotion.”

He shot the film in color because he felt that gave him greater control over the image. “In the DI, especially with black-and-white, I like to be able to assign where in the grey scale something is whether that’s a sky, clothing, a face. By having color you can key it, matte, it and be more precise.”

Black and white also has the effect in this film of accentuating the glorious technicolor of movies like Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, which are vivid memories for Branagh as played out through the eyes of the film’s young protagonist.

“Color is so brilliantly descriptive in film, and even the color of someone’s eyes gives you so much information,” Zambarloukos told the NYT. “But I often find that when I’m making films with Ken, we’re trying to remove information for the audience and present them with what we want them to see.”