Virtual production is big business. Ever since behind-the-scenes tales from The Mandalorian revealed how much of the “location” work took place within ILM’s LED screen-based volume, producers of films and high-end TV have been scrambling to get a handle on this VFX-meets-live-production workflow and grab some of the magic for themselves.

The in-camera VFX (ICVFX) work on The Mandalorian (and later productions such as Obi-Wan Kenobi) saw real-time compositing of CGI backgrounds rendered by game engine software on LED screens, motion-tracked to the camera view, and mixed with the live action on the stage, which in turn took illumination and reflections from the visual effects.

However, virtual production is a broad discipline, with many tools for creatives and filmmakers to explore, not just a buzzword to casually apply to the use of massive LED screen setups.

Virtual Visualization

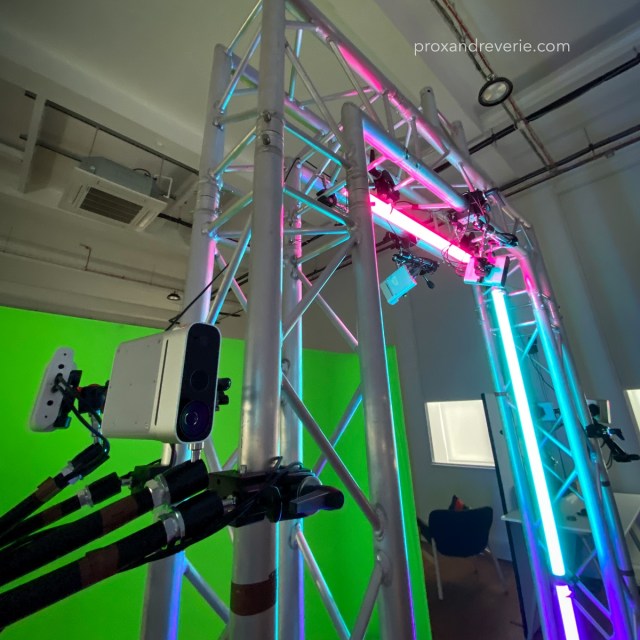

Prox & Reverie is a real-time previs and immersive production studio in Yorkshire, England, offering a live multi-reality production environment called The Forge. This 2,000-square-foot free-roam stage is a “convergence volume” that uses real-time engines such as Unity and Unreal Engine to host explorable virtual universes, populated with motion capture-driven avatars and deploying VR tools to interact with them.

The company was launched to “level up the immersive aspects of mixed reality by tapping into the full potential of XR technology, providing truly interactive experiences that allow creators to create and viewers to step into and experience photorealistic fictional realities.”

“We’ve been very much focused on how you can use virtual production to accelerate projects or to greenlight them,” says Martin Taylor, co-founder and director of Prox & Reverie. “How do you get a raw idea out of somebody’s head and communicate that to a veteran team of set designers and production designers and art directors and producers, all with their very traditional ways of working? The earlier you can do that, then exponentially more time and effort will be saved later on.”

Taylor is convinced that if you get these professionals together inside a simulation of the set, they’ll start building it for real. And with crews in different locations, they don’t have to travel or set up a production base first.

“We’re trying to straddle this this ground between screen production and immersive production, and you need space for that,” says Taylor. “We create quick scans of physical locations, but then we can unroll that scan as a big simulation, with a lot of space to walk around. Our studio is a like a holodeck, we can projection map it onto the walls or we can put it on headsets. And we can start placing virtual props in there. We can invite teams in to come and join those sessions, that can be in the room, or they can be elsewhere.

“They are in a shared virtual space, which is the set inside the virtual production studio,” he explains. “It’s an additive process. You’re not building something and then just scrapping it, and doing another process, you’re migrating to the next stage. [You start with] a very crude kind of block out, then everything just moves along the pipeline, and you end up with final assets on the day without having to rebuild.

“The biggest challenge is convincing people to invest the time upfront, rather than sticking to rigid traditional ways of working,” he continues. “It just aligns the teams so much quicker to start building in the virtual space.”

In addition to its own XR space, as an end-to-end service provider Prox & Reverie will work with a dedicated LED studio when required. “We have carefully chosen partner vendors close by with lots of experience, they’ve learned all the flaws and the pitfalls,” he says. This relationship has other benefits.

“Normally when you think about previsualization, it’s of the actual scene itself, you’re thinking about the framing,” he says. “But you also need previsualization for how the studio will run on the day. You need a digital twin of the studio, showing how the LEDs will be set up, whether you need a roof and floor, where the physical set is and what will it look like to the camera. If you’re new to it, there are so many ‘gotchas’, things that you’ll need to spend money on that you don’t expect. But if you do the right kind of preparation, the amount of time required in the studio is much less because you’ve already seen the shots before you turn up. You’ve done all your tech-viz — you know exactly where the tracks are going, you know exactly where the dolly moves are.”

“Then there are the visual effects [still] needed [with LED screens],” he adds. “LED does a lot of the heavy lifting, but there is still comping and rotating required. Planning, and so minimizing the amount of post work for the shots, is really vital.”

As an example, Taylor describes a recent production that used The Forge: “They had done all of their exteriors, but they wanted to do a whole bunch of car interiors and be able to control the lighting and so on. It was a perfect example for virtual production,” he recalls. “So we used our previs system to give them virtual cameras and all those kinds of things to plan the actual LED shoot itself. And then that was passed on to the LED studio. So, it was virtual production for the virtual production.”

Virtual Locations

Another virtual production technique for pre-production, one that became particularly relevant during the pandemic lockdowns, is virtual scouting, which is used by companies such as Framestore.

“Virtual scouting allows you to explore a set as a whole — the planned physical build and the digital extensions,” says Christian Manz, creative director for film at Framestore. “A production designer is able to see their vision as a whole, walk around it, teleport themselves to multiple viewpoints and even shrink the whole world so that they can get more of an overview — the same as with a card model. Creative changes can be made on the fly or briefed to a team.”

Framestore’s in-house tool, fARsight, runs on a VR headset, with Unreal Engine used to create the virtual environment.

“fARsight allows for multiple users, so that a session can be shared with the production designer, director and DoP, for example” Manz explains. “It has been amazing to see this technology embraced by very experienced filmmakers, who are at first excited to be inside their creations, but then realize what a powerful tool it can be.”

A DP can use the camera tools in fARsight to frame up shots — walking around the set as they would with a physical viewfinder or camera. The camera can be set to match the production’s choice, alongside the full lens package.

“Being able to look at the set from any angle and position can be really useful in finding shots before the shooting day — for example, planning crane shots that could be laborious to find on an expensive shooting day,” explains Manz. “As well as the VR option the ‘camera’ can also be used in unison with standard grip equipment such as a dolly, Steadicam or technocrane to bring a more real-world feel to shots that are planned to be fully digital, maybe even involving a CG character, driven by a motion capture performance, live in the same session. The idea is to replicate the usual set-up you’d have on set, be it in an office or on a sound stage.”

Cameras can be exported to previs or into the final visual effect pipeline, meaning a director and DP will see all of their nuanced work in the final shots.

The technique proved to be invaluable when shooting Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore. “Alongside the usual concept art, previs and animation teams we have in pre-production we had somebody working with the art department, building the key sets and extensions using art director plans and elevations, as well as LIDAR scans that we captured on various locations,” recalls Manz.

“We ran VR sessions with the production designer and DoP and from these, we were able to present the director, David Yates, with key shots that were used as a reference on set and made it through to the final cut.

“Due to the COVID restrictions with crowd numbers we were also able to lay in a digital crowd and walk through them with a camera to work out how we could cleverly use our supporting artists on the day, supplemented with CG crowd in post to turn 80 wizarding supporters into over 4,000,” Manz continues. “It gave everybody the confidence that what we were shooting would fulfil David’s vision once all the final VFX work was completed.”

“Being able to look at the set from any angle and position can be really useful in finding shots before the shooting day — for example, planning crane shots that could be laborious to find on an expensive shooting day. As well as the VR option the ‘camera’ can also be used in unison with standard grip equipment such as a dolly, Steadicam or technocrane to bring a more real-world feel to shots that are planned to be fully digital, maybe even involving a CG character, driven by a motion capture performance, live in the same session. The idea is to replicate the usual set-up you’d have on set, be it in an office or on a sound stage.”

— Christian Manz, Framestore

The technology can also be made more portable. Framestore used an iPad version, fARsight Go, on set to visualize the digital extensions and environments in conjunction with the physical set. It utilizes Apple’s ARkit framework for tracking, human pose estimation and depth-based compositing.

“With a quick calibration it was possible to walk, untethered, around the set to help find a shot with the DoP George Richmond, or to work out eye lines with the actors,” says Manz. “Everybody got quickly used to having it available and it was great to see it being embraced. It gave George the confidence to frame in a sound stage, knowing what the final composition would look like when he saw it several months later in the DI — there were no nasty surprises.”

Photogrammetry was also used. “We used drone-mounted cameras in China to capture thousands of photographs, which, once processed created a vast amount of geometry which we used to create our environments for one of the opening sequences of the film,” Manz recounts. “We also did this type of capture from a helicopter in multiple locations, as well as the more standard LIDAR and texture photography, all ahead of the main unit shoot. Being able to use all of this data, with the art department, to visualize the extended world of our film on set was invaluable.”

Greenscreen Thinking

Butcher Bird Studios, a full-service creative and production studio in Glendale, California, has also been exploring the non-LED side of virtual production for clients such as Netflix and Twitch and corporate demos.

“A lot of people are working inside of LED volumes right no w, for the obvious reasons you get that reflectivity, the play of the light, and — not least — you’re stimulating your actor’s imagination with the set, or rather the world built around them,” says Butcher Bird managing partner Travis Stevens.

However, LED screens are expensive investments and need maintenance, as well as an experienced crew. Furthermore, according to Stevens, the LED volume approach can introduce lag into the virtual production process, occurring when you switch from camera to camera. “It’s brief, but it’ll take milliseconds for the environment to catch up with you after you pop over to the [next] camera,” he explains.

Instead, Butcher Bird shoots in a greenscreen set and uses Unreal Engine in combination with Blackmagic Design’s Ultimatte 12 system.

“We are working on a greenscreen stage because we’re leaning into the live switching side of it all, [creating] programs with three-camera setups that are either live broadcast or live to tape,” he details. “We bring in whatever camera lens data we’re using, or grabbing our lens data from ARwall, marrying all those components inside the Ultimatte then bouncing it out to our live switcher.”

With a computer running Unreal dedicated to each camera, the team can switch cameras with no lag in the feed for the real-time environment. Camera operators have a monitor that shows them the final composite looks like, to enable them to rack the cameras and move both physical and digital elements into focus, while clients view the live composited production on still more monitors dotted around the set.

Another component is lighting, integrated into the virtual stage via DMX. It’s this added layer of shadows and contrast that really sells the illusion, says Stevens, leading clients to often perceive set elements as physical when the whole set is in fact completely computer-generated.

“The tools are getting better and they’re getting closer to real-time. Once we’re able to get pixels that look just as good as something in a major blockbuster in real time, I don’t know why people wouldn’t be using virtual production. The only difference is you shift all your post to the pre-production, and you can see your final result while you’re shooting. I think within 10 years, most productions will be using some variation of virtual production.”

— Travis Stevens, Butcher Bird

“When you’re working with these virtual environments, you start really appreciating tiny little things,” says Butcher Bird Studios’ director and co-founder Jason Milligan. “For instance, early on when we were doing a bunch of experiments, we aligned some of the 3D geometry with the physical greenscreen wall in 3D space. If you leaned against the wall, you would cast a shadow on a virtual building. It was so convincing, primarily just because of that little bit of shadow. And it’s just little things like that, which really help us sell it.

“Even on a small greenscreen space, we can make it look like we’re inside this enormous environment. A few years ago we did a show called Orbital Redux, which was a live sci-fi show set in outer space. We built the spaceship, you could look at outer space through some monitors and [we had] various other interfaces and monitors, but we were very limited by what we practically could create,” Milligan continues.

“If we were making that show today, we could do things like actually put our characters on the surface of the moon, or on Mars, or any number of other things. The whole show wouldn’t need to take place only inside the spaceship, because these tools have opened it up to where, in an affordable way, we could put these people in all these environments, and make it look realistic enough that people buy into it.”

Virtual Democracy

Recently, building on its use of the ARFX Pro plugin for Unreal Engine from ARwall, Butcher Bird and the plugin developer together released a lens-emulation solution for live real-time greenscreen compositing, ARFX Lens. It promises to democratize the virtual production process further.

“For live streams, for Twitch streams, for YouTubers, or anyone with a much smaller budget, [virtual production] is opening up this world where we can let our imaginations take us anywhere,” says Milligan.

“The tools are still being developed; it’s not plug-and-play yet,” says Stevens. “We actually spend a lot of time before a shoot, trying to figure out why something isn’t working, why something isn’t interfacing properly, trying to take the currently existing tools and embed them so they do what we want them to do. But companies like Epic Games and Unity are both working specifically towards that end. Epic’s Unreal Engine 5 is very much tailored towards working with virtual production tool sets.

“The tools are getting better and they’re getting closer to real-time. Once we’re able to get pixels that look just as good as something in a major blockbuster in real time, I don’t know why people wouldn’t be using [virtual production]. The only difference is you shift all your post to the pre-production, and you can see your final result while you’re shooting. I think within 10 years, most productions will be using some variation of virtual production.”