You’d be hard-pressed to find someone who hasn’t at least heard of the Netflix series ‟Baby Reindeer.” It’s one of those watercooler series that everyone will have an opinion of — whether disgusting, moving, discomforting or compelling. It shot to number one globally on Netflix’s charts.

It’s the story of struggling comic Donny and Martha, a woman who won’t take no for an answer. She stalks Donny to the extent of sending 41,071 emails, 350 hours of voicemail, 744 tweets, dozens of Facebook messages and letters over several years.

But as viewers will be aware, this is only half of the tale, which is largely based on the real-life experience of Richard Gadd, who wrote and starred in the show.

“It is a stalker story, but it’s a stalker story with a twist. It shows the side of stalking which isn’t necessarily black and white,” Gadd says in a making of video (watch below).

The series stems from his own experiences and was first performed as a one man show at the Edinburgh Festival, which he also performed on stage in London.

“And it was at that point that Netflix came to me were like, ‘Have you ever thought about putting this in a series?’ and I was like ‘Yes, I have’. And it was a hell of a journey.”

Everyone wants to talk about episode four, which is where the story really shifts its register into dark, dark places. Donny is depicted in an on-screen a rape, which Gadd says he experienced in real-life. It also includes scenes of grooming, drug abuse and nightmare drug experiences.

“It was a hell of a thing to write and shoot,” Gadd says. “It kind of shows the side of abuse that I don’t think we’ve seen before.

“I still think there’s an idea that sexual abuse is a kind of a pill and a drink that dissolves and someone wakes up and they don’t know where they are. And that does happen. And that is a big problem.”

Gadd says he went through hundreds and hundreds of drafts of each script, finally finding what he wanted in episode four that was the key to the show.

“I fully believe that writing is rewriting,” Gadd told Krista Smith at the ‟Skip Intro” podcast. “You get there through constantly rewriting and questioning. I remember having a moment when I wrote episode four, where I thought I’m sort of capturing the tone of this.

“Now I think I understand what this is. The kind of weird humor mixed with the darkness, the sudden lightness, but then the sudden darkness.”

He says he shed physical weight to play the scene. “I sort of really wanted to capture the brokenness that I felt at the time not like method acting or like I’m in character all the time, but I really wanted to feel what I felt back then. And so I did a lot of psychological, quite painful recall and trying to get my body into place where I felt vulnerable.”

However, ‟Baby Reindeer” doesn’t demonize the stalker, Martha. We feel sympathy for her, in part because we feel the vulnerability of a person who has experienced what Donny goes through in episode 4.

“I really believed in the show, and I thought that it would be liked — but to this scale?” Gadd told Skip Intro. “I never thought in a million years. It’s such a singular idiosyncratic sort of experience, a niche story of a comedian and his odd relationship with his stalker and all the things that have happened in his past. It’s just struck a chord with so many people. It’s kind of overwhelming.”

Donny’s questionable actions in the course of the drama only serve to highlight the humanity of his situation.

Gadd refuses to be drawn any further on the moral debate around the show. He said, “My ultimate hope is that it moves people, that it touches people, and it affects people. It’s born out of true events. It’s born out of a real life happening. Ultimately, it is just an autobiographical story that I felt the need to tell, the story of a messed up period in my life.”

Lensing ‟Baby Reindeer”

The series is directed by Weronika Tofilska and Josephine Bornebusch, and it was shot by Krzysztof Trojnar and Annika Summerson.

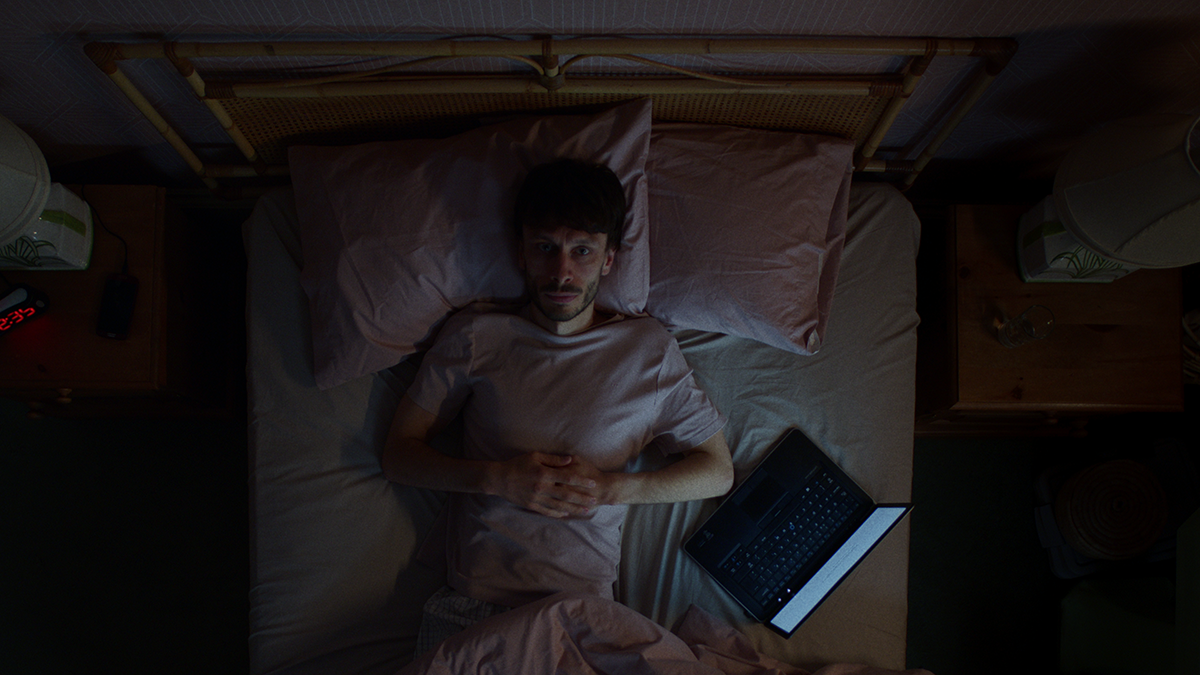

Trojnar lensed the first four of the seven 30-minute episodes. Speaking with Ben Consoli of the ‟Go Creative” podcast, Trojnar said his initial creative conversations were about the character being stuck: “That kind of sense of intensity and oppression the sense of the world pressing down on the character, or Martha intruding into his life was how we decided to portray the state of the character.”

Although the series is in London, they chose to deliberately keep the frame claustrophobic, so we can’t really see too much of the city.

“We never show too much sky,” says Trojnar. “There is no sense of comfort or space, apart from one scene when he’s in Edinburgh, and it’s a flashback where everything feels a little bit more optimistic.”

Trojnar puts his Alexa Mini LF camera up close to the characters, invading and crushing their space. He says he fought to include non-obvious shots, such as the coke being poured.

“It was so important that we see it from the top, we see it from Donny’s perspective, as you would looking down in the counter, you would see it as a top shot.

“This is really important that it gets established that way and it’s its first one of the first shots of the film so we really need to pay attention to it.

“Obviously, you could just plunk the camera and shoot it really fast without doing the whole rigging to achieve the top shot but you would feel the difference on the screen.”

Color Theory in Action

Baby Reindeer was a particularly fascinating job for Senior Colorist Simon Bourne of Company 3 London.

The filmmakers, including Richard Gadd, who was very involved in every facet of the filmmaking, were after a grade that really made its own statement and a colorist who wasn’t afraid to push things beyond a safe sort of look, especially as Gadd’s Donny character descends into ever more frightening circumstances.

“All the colors had to be very bold,” Bourne recalls. “We definitely pulled away from a wide color palette. In fact, the palette is actually quite small. For example, there are almost no blues at all.”

His work started before shooting began with a show LUT that would bring the dailies partway into the realm of the intense, bold look that the final version would have without being so constraining as to limit what he could accomplish during the final grade.

Some people, he says, want to put too much into the LUT, which he sees as “seventy-five percent of the work. When we did final color, I graded through that LUT to pull more out of the shadows and fine-tune everything shot by shot. I’d sometimes blend the LUT, and I didn’t use it at all for some shots. I just built the look from scratch.”

Throughout the series a small number of colors stand out. Some greens, some yellows and red most of all. This naturally started with production and costume design and lighting, but which he enhanced in Filmlight Baselight through keying and drawing shapes around portions of the frame and either bringing out the red that was there or pushing some things that weren’t towards the red realm. He did this frequently for scenes set in the pub where Donny works and in some of the other locations.

Nowhere was the red motif more pronounced than in the apartment in the much-discussed Episode Four in which Donny finds himself in a compromising position with another character.

“There were parts that were almost all red,” he says. “But we didn’t want it to just look like a red wash over everything because that would just look flat. So, we still built separation into the image. I’d key certain elements of the scene and just make them red. I’d build shapes around certain parts of the room that had a lot of red and make them a deeper red.

“The outside lights were yellow, so I isolated them in Baselight and made them red. The practical lamps were clean white, and I did the same.”

The process, he recounts, was very unusual for the degree to which he was encouraged to push the look and, of course, for the whole business of working in collaboration with both the creator and the subject of such a dark, revealing primarily true story.

“I don’t know anyone who’s ever gone through that,” he says. “It was unique for everybody, but he was very professional. He was heavily involved in everything — from the color to the edit to the music. He was very hands-on frame by frame by frame, but also very open to ideas.”

Why subscribe to The Angle?

Exclusive Insights: Get editorial roundups of the cutting-edge content that matters most.

Behind-the-Scenes Access: Peek behind the curtain with in-depth Q&As featuring industry experts and thought leaders.

Unparalleled Access: NAB Amplify is your digital hub for technology, trends, and insights unavailable anywhere else.

Join a community of professionals who are as passionate about the future of film, television, and digital storytelling as you are. Subscribe to The Angle today!