DIRECTOR FRANCIS LAWRENCE ON “The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes”

TL;DR

- Director Francis Lawrence explains how the appearance of a new book by franchise author Suzanne Collins compelled him to do another “Hunger Games” movie.

- He says the biggest challenge was to have the audience root for young Coriolanus Snow in the knowledge that he will become the fascist dictator of Panem.

- While the film franchise split the final book of the trilogy into two films, in a move that angered fans, Lawrence was adamant he didn’t want to make that mistake again.

- The director referenced Gene Wilder’s Willy Wonka for the character of chief gamemaker Dr. Volumnia Gaul, played by Viola Davies.

- Regular director of photography Jo Willems says that even though these are sci-fi movies, he tries to shoot them in a naturalistic way.

“Welcome to Panem,” from “The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes”

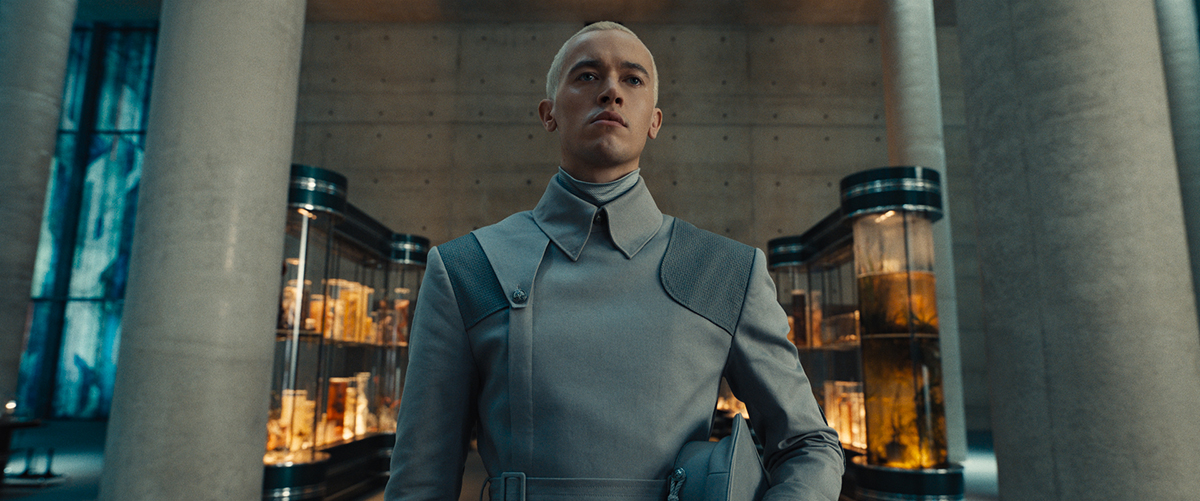

Let the games begin — again. The Hunger Games are back, this time as a prequel telling the story of young Coriolanus Snow, who will grow up to be the tyrannical dictator ruling the sci-fi dystopia of Panem in the four previous hit films.

Also returning is director Francis Lawrence, of whom Jacob Hall at Slashfilm says, “Through his lens, what could’ve been a boilerplate YA series has leaned into the aggressive, the political, and the deeply moving.”

While Gary Ross directed the first film in the series — adapted from Suzanne Collins’ dystopian novel of the same name — Lawrence came aboard for the sequel, 2013’s Catching Fire, and stayed to helm the climactic two-part finale, 2014’s Mockingjay – Part 1 and 2015’s Mockingjay – Part 2.

“I thought I was done,” Lawrence tells A.frame‘s John Boone, “but not because I didn’t want to do more. I thought I was done because Suzanne, the author, was like, ‘I’ve been on this thing for 10 years. I’m going to write plays. I’m going to do other stuff. I’m done.’ Which I could totally understand. I’d been on the movies for three, four years, so I certainly wanted to do something else for a minute, too.”

In 2019, Lawrence and franchise producer Nina Jacobson received a call from Collins. “She said, ‘Hey, I know this is a bit of a surprise, but I’m almost done with a new book.'”

That book is The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, adapted by Lawrence into a script that took him two years to write.

“I think the only thing that intimidated me is that I feel like people are conditioned to believe that a Hunger Games movie is over when the games are over,” he tells Boone.

“So there’s just this feeling that people have, ‘Oh, you build up to the games. You get to the games. The games are over. Movie done.’ And the truth is, all the questions that are set up at the beginning of the movie are not answered by the end of these games, and there’s still a fair amount of story to tell.

“I found that very exciting. I liked that there was a different structure, that it wasn’t just ending with the games, that the games are just part of a much larger story — especially for Snow. But I knew that we were going to have and will always probably have a bit of a hump, just because people are conditioned to feel that.”

There’s a vogue for lengthy cinema experiences, and at 157 minutes this movie is no exception. The Hunger Games has form, though, in splitting the final book of the trilogy into two films. Lawrence was adamant he didn’t want to do that again.

“We got so much s**t for splitting Mockingjay into two movies — from fans, from critics,” he tells Boone. “And weirdly, I understand it now. It’s episodic television or something.

“You can either binge it or you wait a week and a new episode comes out, but to say, ‘You have an hour-and-a-half-long episode of TV and now you have to wait a year for the second half,’ that’s annoying, and I get it. So, that was not going to happen on my watch this time around.”

Creating Coriolanus Snow and Volumnia Gaul

He says the biggest challenge in nailing the narrative was to have the audience root for Snow (Tom Blyth), in the beginning, “empathizing with him, while making sure that the elements of the need for ambition, some of the greed, some of maybe the genetic darkness that’s in him from his father, that all those seeds are planted. So eventually, in his descent into darkness, you find it sort of truthful.”

That arc is reminiscent of characters like Annakin Skywalker’s transition to the dark side over the course of Star Wars episodes one to three, but Hall tries to draw Lawrence into making explicit parallels with Donald Trump.

“It’s a real 2023 mood for a movie to be about how this person you really like is actually a fascist. It feels very timely right now,” he says.

Lawrence replies, tactically, “Yes, yes, for sure. But we get to see him formed into one. He doesn’t start as one.”

For Viola Davies’ character of chief gamemaker Dr. Volumnia Gaul, the director’s reference was Gene Wilder’s Willy Wonka.

“One could consider her a villain in this movie, but she does think she’s doing the right thing and what she’s doing is important,” he said to Boone. “She certainly is a very specific voice, philosophically, in the movie. But the Willy Wonka reference was more that her joy is actually in the creativity of the work that she’s doing, which informs the hair, the makeup, the wardrobe. That joy and the odd, creepy creations reminded me a little of the sinister underpinnings of Gene Wilder’s Wonka. That was my reference for her, which she totally got!”

He adds, “I have to admit, I was a little nervous bringing that up to her, but she totally got it and completely went for it.”

READ MORE: How The Ballad Of Songbirds And Snakes Director Made A Vital Hunger Games Prequel (Slashfilm)

Creating a Naturalistic Look for a Sci-Fi Franchise

Also returning is Belgium cinematographer Jo Willems, with whom Lawrence has worked since starting out shooting music videos (graduating to work for the biggest names in the business including Justin Timberlake, Pink and Lady Gaga). Willems shot the second through fourth movies in The Hunger Games franchise and Red Sparrow, also directed by Lawrence — all starring Jennifer Lawrence.

While Catching Fire was shot on 35mm with anamorphic lenses, “over the years we progressed our style, we went into digital and then ended up shooting large format,” he tells Gordon Burkell at Filmmaker U. “We always try to get more and more intimate with the characters and we have just ended up shooting wider and wider lenses. Even though they are sci-fi movies, I try and work in a naturalistic way.”

For this installment of the series, Lawrence and Willems opted for the Alexa’s 65 mm after Lawrence had worked with it on Apple TV+’s “See,” according to an interview with IndieWire. “I really started to see how, sort of, different the depth of field is and how the lens is for that camera and that sensor in general,” Lawrence explains. “You can actually go much wider without getting that kind of warping and distortion on people’s faces. … You really get that intimacy and maintain the scope at the same time.”

Lawrence tells Filmmaker U, “I also like shooting in very natural light, so a large part of the movie, where you end up in all these natural light landscapes, I think they look stunning.”

The director says he enjoys post-production more than shooting which he finds really stressful. “I wake up every morning with a knot in my stomach because you really only have that day to try to get the scenes that are assigned to that day,” he says in a first-person essay written for MovieMaker Magazine. “So many things could go wrong — could be somebody’s personality, could be somebody’s sick, could be something’s broken, or something’s not working, or we didn’t plan something correctly, or it’s raining and you need sun. I find it so constantly stressful.

“But post, once you have all the material, you come home and the lifestyle is much more civilized again, and you sit with your editor and you go through it all, and then you see the movie come together in a whole new way. And there’s something really gratifying about that.”

READ MORE: Francis Lawrence: Things I’ve Learned as a Moviemaker (MovieMaker Magazine)

Presumably, if this film is a hit, there will be another story set in the franchise to come.

“I would totally do another one, but it’s all up to Suzanne,” he says to Boone. “It’s the same as after the Mockingjays. I said, ‘I would come back 100 percent if asked.’ But it’s got to come from the mind of Suzanne, because she truly is the author of these things. But also, she writes from theme and writes from a real idea, and I think that’s what gives these stories their substance and their relevance.”

READ MORE: Why ‘Hunger Games’ Director Francis Lawrence Said Yes to ‘The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes’ (A.frame)

Color Grading Songbirds and Snakes

“We knew the film would have a variety of strong looks,” says Senior Colorist Dave Hussey of The Hunger Games: The Balled of Songbirds and Snakes. Hussey, who works at Company 3’s Santa Monica, California facility, had collaborated frequently with director Francis Lawrence and cinematographer Jo Willems, both individually and together, on projects including the Apple TV+ series See and Jennifer Lawrence spy thriller Red Sparrow.

As they always did, Hussey and Willems started the process of developing looks during preproduction of this prequel. Starring Rachel Zegler as Lucy and Tom Blyth as a young Coriolanus Snow, Songbirds and Snakes is set 64 years prior to the events in The Hunger Games. The discussions between colorist and cinematographer would involve fleshing out a look for the film, which would be re-introducing viewers to a very different District 12 than they’d seen in previous Hunger Games movies.

“The Arena needed a gritty look for the fight scene,” Hussey says of that key location. The primary city, Panem, would be represented in its earlier times, still feeling the results of a recently concluded war. “It needed an industrial feel for the urban parts of District 12 and a richer and more colorful look for the rural scenes. We also knew we would want a very stylized and ominous look for the hanging tree” — the infamous site of many executions which is frequently referred to in previous films but shown for the first time here.

Hussey created one main show LUT (lookup table) for Willems to shoot through, which would display for the cinematographer and all department heads an approximation of a final look on set and subsequently in dailies. “Since the prequel is set 64 years in the past just, after an attempted insurrection, we wanted to give the film a grittier look for many of the scenes. We also developed a LUT that helped get us there,” Hussey says. “In some scenes, like those with the hanging tree, we wanted to push the grittiness even further, so we blended a combination of LUTs together to achieve this.”

Once time for the final grade came around, Company 3 started receiving the stream of VFX shots that would be part of the film. VFX Supervisor Adrian De Wet would come into the color sessions at this point to offer input about how all the shot elements and the color was coming together.

“Grading the arena fight scenes was particularly enjoyable,” Hussey recalls, “because they took place during different times of day and involved a massive number of VFX shots. Adrian, Jo Willems, Francis Lawrence and I collaborated closely to bring all aspects of every shot together. We had recently worked in a similar way on ‘Slumberland’ for Netflix, which also required blending a large amount of VFX work.

“We did an overall balance of the scenes using different color temperatures to accentuate the different times of day and then by adding grain, using Power Windows with tracking, and making use of a number of sharpening tools we worked to subtly help guide where we wanted the audience’s eyes to be looking moment by moment.”

Hussey also used Resolve to handle some specific work isolating each of Coriolanus Snow’s eyes, making them the intense blue that the character of Snow (a younger version of the villain played by Donald Sutherland in the earlier films) called for.

As happens sometimes in post, they were asked to present a graded trailer to the studio before completing the final grade for the film. “We were able to nail down many of the looks during this time,” Hussey recalls. “That was very helpful because at that point we had locked down many of the scenes before we started the actual grade of the film. Jo and Francis are both very decisive when it comes to coloring so things moved very quickly.”

For the grain Hussey added the production decided to go with Live Grain Real-Time Motion Picture Film Texture Mapping — a proprietary tool licensed on a per-project basis, which many swear by due to the large amount of control over it offers users to adjust fine detail. “We went fairly aggressive initially with the grain and then backed it off a bit as we finessed all the scenes,” Hussey notes.

While colorists often grade projects that have a Dolby HDR deliverable first in HDR and derive P3 and subsequent versions from there, Hussey started in P3 (still by far the version most cinemagoers would see) and then, once the filmmakers signed off on that, executed new separate passes for Dolby Cinema and then Dolby Vision for streaming and other home deliverables as well as an IMAX pass also did for select theaters.

“In terms of the look, we always tried to stay relatively true to the P3 theatrical version,” Hussey explains, adding, “Of course, the HDR versions have a little more pop in the blacks and the highlights, but it wasn’t about making a new look. It was entirely about enhancing the P3 version that Jo and Francis signed off on.”