Mitchell, Dean, Liddy, Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Hunt, Magruder, McCord — the infamous rollcall of all the president’s men etched into the history of Watergate by the book and film, whose heroes were the journalists that uncovered criminality in Nixon’s White House. But there’s another side to this story that foregrounds the role of the women who were kept in the background then and sidelined in subsequent accounts of the events of 1972-74.

That is what Gaslit sets out to redress. The new Starz original series focuses in particular on Martha Mitchell (Julia Roberts), the wife of Richard Nixon’s attorney general, John Mitchell (Sean Penn), who was several steps ahead of Woodward and Bernstein and had the courage to blow the whistle on the whole house of cards.

If you haven’t heard of her story, that’s because she was publicly vilified for disloyalty and HIS-tory has done a good job of propping that narrative up. Similarly, the role of Maureen “Mo” Dean (Betty Gilpin) wife to White House Counsel John Dean is brought out of the shadows.

“I don’t know if Gaslit will be able to replace All The President’s Men in popular consciousness — or if it should — but we are reframing those events through characters that were marginalized and were collateral damage of this giant power structure that was incredibly controlling of all the levers of American democracy,” says editor Joe Leonard (who previously worked with exec producer Sam Esmail on Mr. Robot and Briarpatch and went to film school with showrunner Robbie Pickering).

“A lot of the characters we feature are peripheral in All The President’s Men,” says Leonard. “[The book and 1976 Oscar-winning film of the scandal] took the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern [Woodward/Bernstein] and made it about them in the public perception. In Gaslit you are meeting characters that you don’t really know and seeing these momentous events through their lens. There is the element of the ticking clock, characters whose fate is doomed.”

Leonard had already been engrossed by Slate’s “Slow Burn” podcast on which Gaslit is based, and followed that up by listening to the audio book King Richard, an account of Watergate by Michael Dobbs, to immerse himself in context.

“You have to learn about the real events then you almost have to forget them because what we’re doing is not strictly historical. The facts don’t change but this is not a documentary.”

In dramatizing the power dynamics and behind the scenes relationships of very public figures and headline events Gaslit is reminiscent of The Crown.

“The tragedy of Martha Mitchell is that she wasn’t remembered as a truth-teller,” Pickering explains. “She wasn’t remembered at all because people like her don’t write the history books. Martha’s story is so amazing because she was gaslit on a national stage and she was crucified for telling the truth. Her story didn’t end well and I believe that when somebody is gaslit like that, it’s our duty to tell the truth and show that they were telling the truth. That’s what I’m trying to do with the Martha Mitchell story. It’s a story about us, our country, and how we, as people, find convenient scapegoats in desperate times.”

Leonard cut the pilot, and explains the importance of establishing the series’ tonal balance. “Martha was an arch conservative and a strong woman in a very alpha male world, a feminist in some ways. We had to ground her scenes and really find the tone where she exists in this world and one where John Mitchell. Finding what their power dynamic is was crucial to the marital drama,” he says.

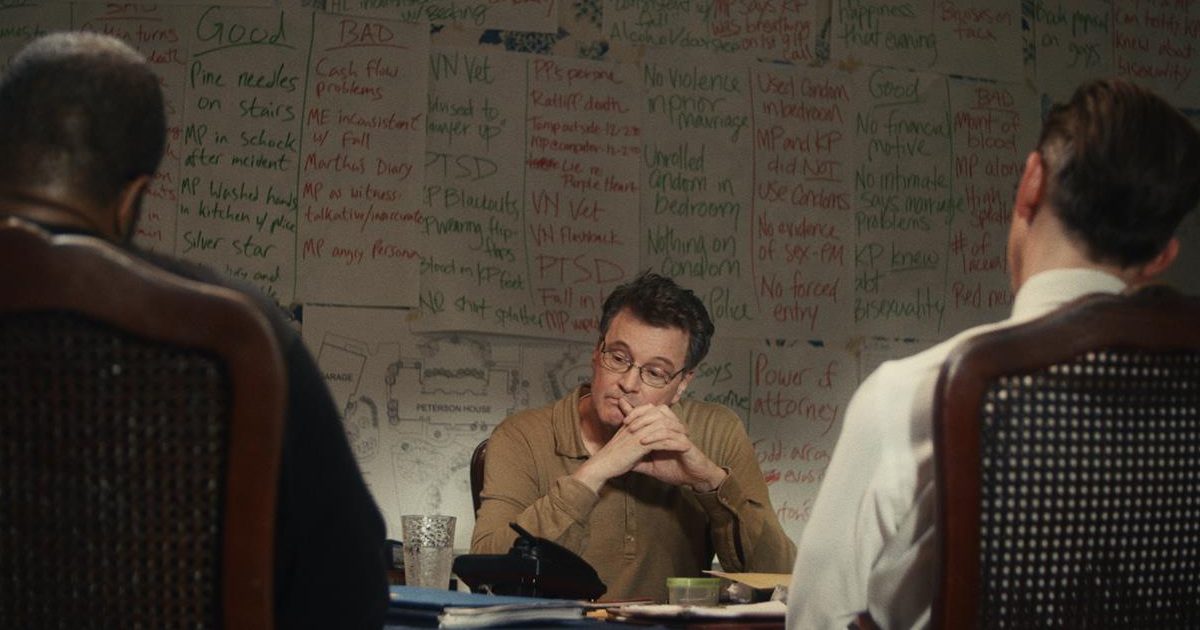

“Also in episode 1 we meet John Dean (Dan Stevens). He’s ambitious, wants to climb the political ladder, but he makes the wrong decision in the first big scene with Mitchell and where the whole series really begins,” Leonard continues. “It’s one pressure-filled bad decision in a smoky room. He makes the wrong call [to cover up the break in] and from then on his fate is sealed as he gets dragged in. Editorially the challenge was to tonally balance these storylines.”

The eight-hour series was directed by Matt Ross and shot in blocks, meaning that all the scenes set in the White House were shot in one go, then all the scenes set in the Mitchell’s apartment, and so on. That meant Leonard and fellow editors Franklin Peterson and Lauren Connelly were editing their episodes simultaneously as scenes came in.

NOW STREAMING — BEHIND THE SCENES OF FAN-FAVORITE SERIES:

As the streaming wars rage on, consumers continue to be the clear winners with an abundance of series ripe for binging. See how your favorite episodics and limited series were brought to the screen with these hand-picked articles plucked from the NAB Amplify archives:

- “Severance:” Now, About Solving the Work/Life Balance…

- Entering “The Gilded Age”

- Class Is Definitely Not In Session: The Horror Delights of “All of Us Are Dead”

- “The Dropout” Is a Slow-Motion Car Crash (and We Can’t Look Away)

- The (Unavoidable) Universal Appeal of “Squid Game” Is By Design

“I would get one or two scenes for the pilot and episodes 4 and 7 and these were like puzzle pieces waiting for the rest of the material to fit around it,” Leonard says. “It meant that some of the first things I cut had to be recut as you learn more about the pace and structure of the story. On the other hand, some of that early work helps inform scenes in later episodes. I had a major six-minute scene for episode 1 only come in on the last week of shooting but at this point I knew the characters and, in a day or two, I had it in shape where I would probably have spent weeks fiddling with it if I’d worked on that four months previously.”

The editors also screened scenes for each other and talked about story development. “Watching other editor’s work is really helpful. There are things other people bring to character development. For instance, John Dean does this gesture when nervous, or when he’s lying he does this. These little things noticed in performance by each of us help build and inform character.”

All power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely, the age-old theme as resonant today as it was in Shakespeare’s time. There are clear parallels between the Watergate scandal and the opportunistic subordinates, deranged zealots, and tragic whistleblowers of our current politics.

“It’s the nature of a power structure to impose its will,” Leonard observes. “In the last 10 years we’ve witnessed the rise of Trumpism and the attempt to control and subvert democracy by essentially controlling the levers of power.”

The story is also universal in the sense that we might identify with the players caught up in it.

“There are dozens of Deans and Martha Mitchells in and around government now. In Martha with have a woman who wasn’t believed. She was called crazy and a drunk, which might have been true — it is a complicated story. But she was still right.

“I think that what we are trying to do in Gaslit is to understand their actions rather than to demonize. I had a lot of compassion for the characters even at their worst,” Leonard says. “You have to come from a place of extreme empathy and the job is to understand them in telling the story.”

He likens the work to Pablo Larraín’s features Jackie and Spencer, “which are like a dream of the reality but really coming from places that empathize with the truth of the emotions of those involved.”

Gaslit Cinematography

The show’s visuals don’t scream “the seventies,” but provide an unobtrusive backdrop to capturing the mood of the era.

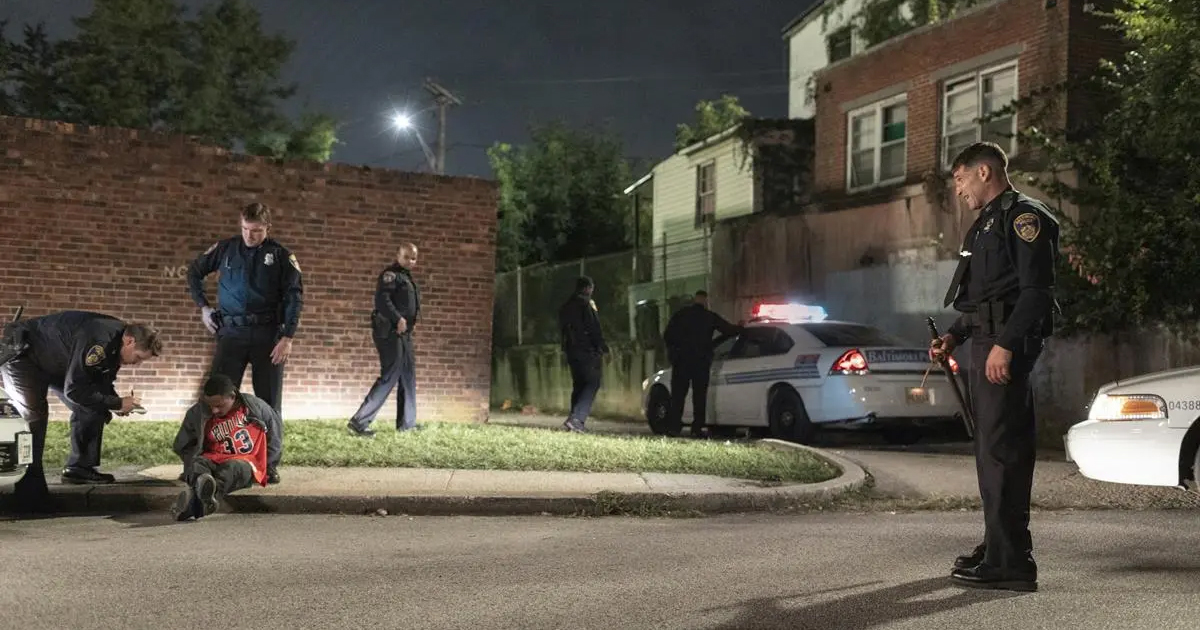

“Matt wanted it to look bold, unlit, and found,” says director of photography Larkin Seiple (who has previously shot many music videos and also provided additional photography on Spider-Man: Far from Home). “Not a documentary and not a movie, just something that looked like these people walked in a room and turned on the lights.”

That meant that the choice of light sources was differently imagined, coming from windows and practical lights embedded in the production design, as opposed to large-scale diffusion setups.

Seiple also decided that to achieve a realistic seventies look he would use period equipment and methods wherever appropriate. “We chose to shoot on vintage lenses from the seventies to give it a softness,” the cinematographer explains. “And we use different lens sets for different characters — softer lenses for Martha, harsher lenses for John Dean — there’s a mish-mash of lenses throughout the story to build something subtle into the photography for each character.”

The DP deployed hard light and some fixtures from the 1970s. All the news footage and game shows were shot on Ikegami cameras from the 1970s that look like they’re from the period.

“We were leaning on the classic innovation from back then, and they’re pretty messed up, distortive, and with color bleed,” he said.

Seiple was nominated for a 2022 Emmy Award for Outstanding Cinematography for a Single-Camera Series (Half-Hour) for his work on the first episode of Gaslit, “Will.”

In an interview with IndieWire’s Erik Adams and Chris O’Falt, Seiple described his approach to shooting the series. “On Gaslit, our director, Matt Ross, wanted to use the visuals to make bold choices and bring a sense of humanity to each character and their moral ambiguity, since we follow not only the heroes but also the villains and everyone in between during the Watergate scandal. We decided to use different lens sets between the main characters to enhance their perspectives and match their emotional arc and mental state.”

He continues: “We spent a whole day testing every lens Keslow Camera could find in a small motel room set with stand-ins. We were chasing an image that was harsh and real but also compelling and photographic: an elevated version of 1970s street photography. We shifted between dramatic looks of blown-out windows, strong back light, hard front light, fluorescents, and tungsten practicals. We pushed the lenses to expose their flaws because we wanted to light the film in a very real manner to combat the fact that we were shooting primarily on stages.

“We landed on Canon K35s for Martha, the martyr of the story, as they felt soft and intimate with subtle fall off on the edges. Impressionistic at times. This type of glass also had a raw quality, a flare and veiling that made you feel present in the space,” he said.

“For the villains like Gordon Liddy and his cohorts we danced between Cooke Speed Panchros and Zeiss Super Speeds. The Super Speeds really had a bite to them, an edge and contrast that stood out against the other characters. For flashbacks we opted to use the MiniHawks which created a very fragile looking image.”

Seiple shares that “we also reserved some focal lengths for specific actors, the Super Speed 25mm was only used for Gordon Liddy’s close-ups, lovingly referred to as ‘The Liddy,’ as the lens had a distorted and off-kilter effect.

“Our story is from the past but has many modern political implications so we tried to create something timeless. We didn’t want a gritty 16mm look nor did we want the super sharp large format look with the very modern super shallow depth off field. We found the super 35mm sensor on the Alexa Mini was perfect, it allowed us to still see our beautiful sets while shooting wide open but also softened the images just enough and took the edge off highlights. The cameras were small and lean allowing us to shoot multiple actors at once as performance was the priority and we wanted to let the cast change it up each take.

“Along with the appropriate camera and lenses we also created a ‘look’ for the show with our colorist Alex Bickel,” he referenced. “The look was based a film stock from 1970s: Eastman 100T 5254. It was super contrasty with bold skin tones and very inky shadows. More importantly it didn’t have the cyan shadows that you see in many modern films, but instead has a cobalt blue edge to the night work.”

READ MORE: Emmys 2022: Cinematography Nominees on How They Shot the Year’s Best Shows (IndieWire)

With colorist Alex Bickel and color scientist Bill Feightner, Seiple emulated a film stock of the era, building a LUT to recalculate the color for Gaslit based on period-appropriate stock.

The series’ main set is the Mitchells’ Watergate complex penthouse apartment. It’s a great example of liberties taken with the factual background to enhance the on-screen drama. “The real Mitchell apartment was blander, more humble,” production designer Daniel Novotny explains. “We upgraded the home a bit to give it more cinematic value, more depth. Their real apartment was just a box with low ceilings. It was painted a gray-blue, and the carpet was dingy. We needed to elevate the architectural space, the finishes, and the color palette, to make it look better on camera, and we created a split-level floor plan so that you could have interesting eye lines and camera angles.”

The home reflects Martha Mitchell’s design choices. “She would have decorated, and Mitchell would have come home to her environment. This is her world, her colors, and her choices.”

Set decorator Jennifer Lukehart adds that “the bedroom is private, it’s more Martha, who leaned toward the ornate, but the public space is more austere. I don’t think it was her natural style.”

The absence of Martha Mitchell and Mo Dean from the received story of Watergate was by design.

“History is written by the winners, by the heroes, by the victors,” explains Pickering. “This is a story about the losers, which I think is a much more interesting story

“The challenge of taking on a story about Watergate is knowing the difference between facts and the truth. Gaslit is not a journalistic presentation, but it is the truth about what happened.”

Want more? Watch a roundtable discussion from Gold Derby about the making of Gaslit with showrunner Robbie Pickering, cast member Shea Whigham, writer Amelia Gray, cinematographer Larkin Seiple, and production designer Daniel Novotny: