TL;DR

- David Fincher’s go-to editor, Kirk Baxter, ACE helped achieve a new kind of subjective cinema with Michael Fassbender’s assassin character.

- Although “The Killer” proceeds on a fairly linear trajectory, Baxter says this made it challenging to cut because there was nowhere to hide.

- The rules for the visuals, the movement, and the soundscape were laid down in the film’s opening sequence set in Paris.

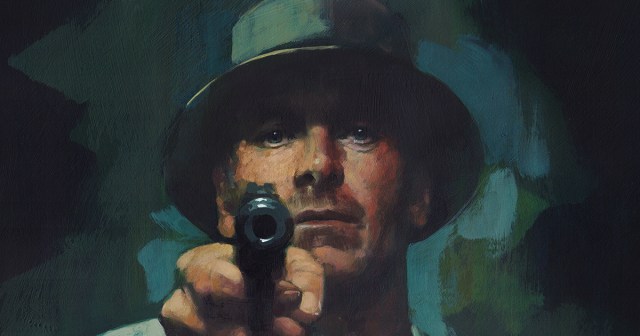

Critics are hailing David Fincher’s The Killer as his most experimental film since Fight Club: “a subjective, cinematic tour de force,” says Bill Desowitz at IndieWire, in which we get inside the mind of Michael Fassbender’s titular assassin after he experiences his first misfire in Paris.

The movie, now streaming on Netflix, divided into six “chapters,” each with its own look, rhythm, and pace tied to Fassbender’s level of control and uncertainty. According to the film’s editor, Fincher regular Kirk Baxter, ACE, the editorial process necessitated the creation of a visual and aural language to convey subjective and objective points of view for tracking Fassbender.

Baxter (Zodiak, The Social Network) goes into detail about working on each chapter with IndieWire. We learn that the opening sequence set in Paris took the most time for Baxter to assemble because it was stitched together from different locations including interiors shot on a New Orleans stage.

“I love the whole power attack, the stretching of time, the patience of what it takes to do something properly,” Baxter said. “And I love that it’s grounded in the rule of physics and how practical it is that each detail in order to do something correctly deserves the same amount of attention.”

Later, in a chapter set in New Orleans, the Killer exacts revenge on a lawyer. The setup prep is slow as he cunningly enters the lawyer’s office dressed as a maintenance worker.

“It was one of the hardest things to put together,” Baxter tells IndieWire. “It’s a little like a Swiss watch in terms of how exacting it can be in his control. David had like 25 angles in the corridor, but when you put it all together, I love how that scene unfolds by playing both sides of the glass [between the office and corridor]. Typically, he’s gonna say as little as possible and his stillness controls the pace, and when he gets fed up, these little, tiny subtle looks from him are letting you know that’s enough and where this conversation stops.”

The nighttime fight between the assassin and a character called The Brute in the latter’s Florida home is depicted as a contest between two warriors in the dark. Speaking to Dom Lenoir, host of The Editing Podcast, Baxter explains how he and Fincher choreographed this fight as well as talking more broadly about the director’s shooting style.

“David does always provide a lot of coverage [and] that gets misinterpreted as a lot of takes [but] what he’s extremely good at is making sure that I’ve got the pieces to be able to move around as needed, or to keep something exciting. It means I can edit pretty aggressively and use just the best pieces of everything. David knows these rhythms he shoots for an editor. So, if it’s a really long scene, you will find in the wide shot that they’ll often be blocking, for example, somebody coming into the room. You sort of work your way [into the scene].”

Baxter says all that matters to him once in production is the material Fincher has captured. “I will read the scene again so that I understand the blueprint of it. You know what its intention is, but then it can be thrown away because David can evolve beyond what the script was based on, whether a location or how our actors are performing. He’ll recalibrate and readjust.”

Although The Killer proceeds on a fairly linear trajectory (hey, like a bullet…) Baxter says appearances can be deceptive when it comes to cutting.

“I found it to be one of the more challenging movies to make because it’s not juggling a bunch of different character lines or going back and forth from past to present and that sort of thing,” Baxter told IndieWire. “It’s just a straight line, but the exposure of that [means there’s] nowhere to hide. It’s like everything is just under the spotlight and you’re not having dialogue and interaction to kind of dictate your pace. It’s a series of shots and everything has to be manipulated in order to give it propulsion, or how you slow it down.”

He continues this train of thought with Lenoir, “It was a challenging movie to make from my perspective because you are showing an expert on the fringes of society but he’s still a person that operates with precision. You’re trying to illustrate that by showing precision. And it is just a lot of fiddling to make things seem easy.”

He also discusses perhaps something that you may not notice in a first watch which is that The Killer doesn’t seem to blink. It doesn’t just happen in this film either but in other Fincher movies where Baxter says he has consciously selected shots of actor’s not blinking.

“I don’t think that it was an effort to remove them through the film,” he says. “It’s just the nature of how his performance was. But there’s been an effort to remove them in previous films when they’re all kind of landing off rhythm. It’s mostly about when you get into the meat of a scene and you’re in close ups and you want something delivered with intention and purpose.”

Audio was crucial to The Killer as well. Rather than be smoothed out in the background with the edge taken off all transitions, Fincher and sound designer Ren Klyce wanted the audio to be driven by point of view. The rules of the film’s soundscape are established in the opening sequence. Given that the protagonist is not predisposed to be chatty, we learn as much from his internal monologue as from his methodological movements.

“We crawl into his ears and sit in the back of his eye sockets instead of how it’s being presented,” Baxter describes to IndieWire. “From the moment when the target turns up, it was David’s idea to try a track that was what he plays in his headphones. And when you have his POV, we turn the track up to four, and when you’re back on him, the track drops down, and you get the perspective of it playing in his ear.”

READ MORE: Editing ‘The Killer’ So That ‘We Crawl Into His Ears and Sit in the Back of His Eye Sockets’ (IndieWire)

They devised rules for how to apply his voiceover but realized they couldn’t have voiceover and music at the same time because there would be too much “sonic noise” for the audience.

“So one’s got to occupy one space and one take the other. The logic said to us what’s blaring in his ears and when he’s in a monologue is when we’re looking at him. That was the rule of what was subjective and what was objective,” says Baxter.

“We tried the notion of ‘vertical’ sound cuts,” Fincher explains. “By which I mean, you’re coming out of a very quiet shot and cutting into a street scene and – boom! — you pick up this incredibly loud siren going by. You’re continually aware of the sound.”

This makes for an unusual but effective experience. For instance, there’s a scene in a Parisian park where the sound of a fountain constantly moves around depending on the featured character’s POV.

Was matching that vertical sound cutting hard?

“I guess even when you’re creating chaos, you’re trying to affect it in your own way,” Baxter tells Andy Stout at RedShark News. “You’re always seeking your own version of the perfect way to do this.”

Jennifer Chung, ACE was one of the assistant editors on the film — part of a 14-strong editing department. She also spoke with RedShark News about the tools they used.

“Obviously we use Premiere, and we heavily use Pix also,” she says. “We do a lot of our communication in post through Pix, especially during production during the dailies grind, where we’re uploading not only the dailies but selects that are coming out so that we can get that to David.”

Adobe After Effects is also used extensively, with the team using Dynamic Links to round trip the content out of Adobe Premiere and back in. Some of the assistants also script, so Python or even Excel, in some cases, were also deployed to help automate some of the critical processes.

The Killer was shot in 8K using RED V-Raptor and according to Chung proved a little tricky initially to grade in HDR.

“We definitely had some kinks we had to figure out early on,” Chung says. “We all needed HDR monitors, but we didn’t have HDR monitors at home, though we had HDR monitors at the office. We also use a lot of Dynamic Links in Premiere, and we were having some color space issues going from Premiere to After Effects back to Premiere, but because we have such a close relationship with Adobe, we were able to figure that out.”

READ MORE: Editing David Fincher’s ‘The Killer’ on Premiere Pro (RedShark News)

In The Killer, the assassin experiences a gradual loss of control that is in stark contrast with his profession’s demand for precision and self-discipline. The film’s voiceover is a key storytelling tool, not only advancing the plot but also reflecting the killer’s internal conflict. This narrative choice is complemented by the film’s editing, as Baxter elaborates in his discussion with Steve Hullfish, ACE, on the Art of the Cut podcast.

“David had outlined that the movie is about process,” Baxter says, explaining how he and Fincher used this idea to help guide their creative decisions. “When it’s the killer’s process — when he is in the driver’s seat — we’re going to be extremely deliberate about everything. The camera will be steady. The pacing will be steady, considered, and exacting. Continuity will rule the day.”

On the other hand, “when things go out of his plan — when chaos erupts — we’re going to introduce camera shake. I’m going to start to jump time slightly, start to clip action and have the freedom to kind of make it more exciting and out of control.”

Baxter likens it to the thriller-horror construction of “stretch everything until you reach that point,” adding, “Most of the series of chapters, or kills, have this similar construction that is stretching process, like taking your time with it, and then exploding into action,” he says. “There’s a great use of the voiceover line at the beginning where the killer says, ‘If you don’t have patience, this is not the profession for you.’”

While the Oscar-winning editor says he can’t entirely relate to a psychopath, he does relate to the concept of process. “I relate to the faith in process to see you through,” he says, “that if you follow all of the your steps of survival, you will get to the other side with the result you’re after.”

Baxter’s approach to working with the voiceover always began with the visuals, he said. “I would just start with the visuals on their own and then try to fit the voice to it.”

Voiceover “is always a wriggly fish because you can keep changing it,” he says. “It’s rather pliable,” he continues, describing how they would add, drop or even entirely rearrange lines.

“There was a lot of voiceover to kick it off, up until the first killer misfire, then it started to streamline back into just a repeating of the mantra but dropping away sections,” he recounts. “So the mantra got shorter and shorter, as he was breaking his own rules, and his own disciplines were starting to erode.”

The sniper scene, occurring near the beginning of the film, helped define how the voiceover would function throughout the remainder of the film. “We’re blasting the music in his ears, The Smiths song up so high that it can’t fit voiceover,” Baxter says. “So it became this rule in the movie, from that scene that then sort of bled out in every direction.”

Baxter’s editing approach was significantly influenced by the film’s music, particularly in key scenes where the soundtrack played a pivotal role in dictating the pace and mood. In the sniper scene, for instance, the loudness of The Smiths’ song was used to such an extent that it left no room for voiceover. This choice led to a rule that was applied throughout the film: voiceover was used where the music wasn’t dominant. Baxter describes this as a balancing act, saying, “When he’s in his POVs, what’s going on inside his head with sound? No voiceover goes on his POVs in the movie. It all goes where the music’s not up at 10.”

The editing was further complicated by the need to adapt to changes in the music track. Baxter recounts how the music selection process was dynamic and challenging, involving various experiments with different genres and artists before settling on The Smiths. He notes, “It was the cherry on top. Always for me, I just loved playing with music: being part of choosing which tracks should go where to have the most black comedy in.”

Baxter also emphasizes the style developed in the film of “punching in and out of the volume of the music — from POV of headphones to blasting full.” This technique became a signature aspect of the movie’s sound design, especially effective in scenes like the sniper scene and when the killer is in the van observing his target, Dolores. The fluctuating music volume played a crucial role in setting the tone and pace, aligning with the visual cuts and the psychological state of the killer.