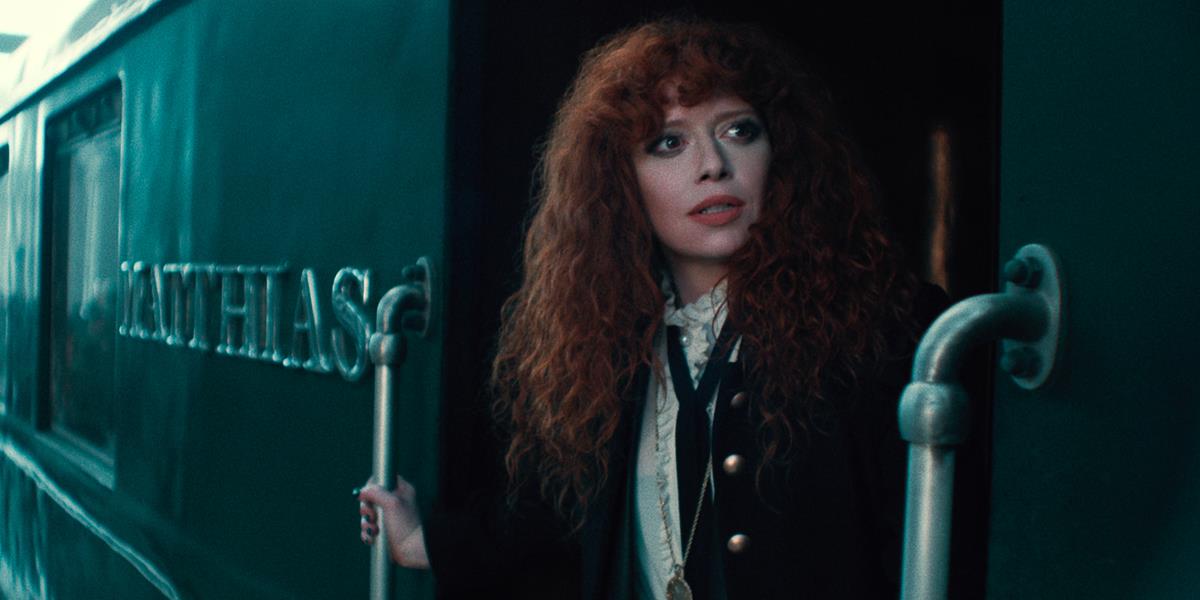

In season two of “Russian Doll,” Natasha Lyonne attempts to answer the question, “Now that I’ve stopped dying, how do I start living?” Cr: Netflix

Emmy Award-winning comedy Russian Doll returns for a second season, but this is no Groundhog Day repeat of the formula that made the Netflix show a hit.

Succinctly, in season 1, lead character Nadia Vulvakov (Natasha Lyonne) repeated her birthday every time she died. In season 2, she travels back in time.

It’s about much more than that, of course. “If Russian Doll was yet another comedy about trauma, it was also a comedy about quantum physics — a curious exploration of the possibility of life in other timelines,” says The New Republic.

Or as Lyonne herself puts it to The Hollywood Reporter, “The idea in season one was, what does it mean to be self-destructive? [The main characters] Alan (Charlie Barnett) and Nadia can’t stop dying until they find a connection. In season two, it’s about: ‘Now that I’ve stopped dying, how do I start living?’ ”

Lyonne elaborated further to The New Yorker, “The bigger question I’m asking is if it’s true that we all have the ability, regarding past trauma, to reorient ourselves around it, or if in fact there is no free will, because it’s a set element of the universe, and therefore we must just radically accept the full weight of the past.”

Heavy stuff for a comedy perhaps, but not in the hands of Lyonne, who co-created the series with Leslye Headland and Amy Poehler through her production company Animal Pictures with the producer Danielle Renfrew Behrens and the actress and comedian Maya Rudolph.

The timeline in season two shifts between 1982 and 2022 and is a riff on Back to the Future, The New Yorker remarks in a comment that Lyonne reveals in another interview to be wide of the mark.

She told Deadline that, “if season 1 was a take on a Groundhog Day time loop, she wanted season 2 to approach time travel differently than Back to the Future.”

READ MORE: ‘Russian Doll’s Natasha Lyonne & Amy Poehler Talk Going Deeper In Time & Character In Season 2 (Deadline)

Either way, as Vanity Fair observes, season two doesn’t feel like a huge departure from the concerns of Russian Doll’s first season, which was also haunted by ghosts of the past.

READ MORE: Russian Doll Goes Underground, and Back in Time, in Absorbing Season 2 (Vanity Fair)

In an early scene, Nadia discovers that she has teleported to 1982, the year she was born. This sets her off on a race to uncover a family mystery and its psychological reverberations. Through seven episodes, parts of which were filmed on location in Budapest, Nadia keeps barreling into the past, connecting the dots between her own sense of dislocation, her mother’s mental-health problems, and her Hungarian grandmother’s experience of the Holocaust.

Some aspects of this draw on Lyonne’s own Jewish heritage, as well as her grandmother’s experiences in Hungary in World War II.

As relayed by The New Yorker, Lyonne’s mother was the daughter of Hungarian Holocaust survivors who settled in LA by way of Paris.

The new season of Russian Doll doesn’t draw on Ella’s story directly, but it explores the rift between a traumatized older generation and a vulnerable younger one, and the ripple effects of what Lyonne calls “damaged love.”

Lyonne says, “I joke that there’s a straight line from Hitler to heroin.”

Her friend Michaela Coel, the creator and star of the British drama I May Destroy You, which is about surviving the obliterating aftermath of sexual assault, says that she admired Lyonne’s willingness to delve into her lowest experiences.

“I don’t know if this will make sense to anyone other than Natasha, but it feels like we are both living life on some sort of dangerous and thrilling edge,” Coel said to The New Yorker. “We’re on two parallel edges. And we’re shouting at each other, and waving, and talking about how cool it is to be alive.”

NOW STREAMING — BEHIND THE SCENES OF FAN-FAVORITE SERIES:

As the streaming wars rage on, consumers continue to be the clear winners with an abundance of series ripe for binging. See how your favorite episodics and limited series were brought to the screen with these hand-picked articles plucked from the NAB Amplify archives:

- “Severance:” Now, About Solving the Work/Life Balance…

- Entering “The Gilded Age”

- Class Is Definitely Not In Session: The Horror Delights of “All of Us Are Dead”

- “The Dropout” Is a Slow-Motion Car Crash (and We Can’t Look Away)

- The (Unavoidable) Universal Appeal of “Squid Game” Is By Design

Russian Doll of Hats and Easter Eggs

Lyonne has taken over from Headland as showrunner, wrote four of the seven episodes, directed three, and had a hand in every aspect of post-production.

“Directing is this whole other third thing that came into my life, and I’ve never felt so at home,” she tells The New Yorker. “It just turns all my defects into assets. Meaning, you know, being hyper-decisive and obsessive and tireless.”

The new season’s format “allows Lyonne to reveal her character’s real antecedents, the most obvious of whom seems to be the shambling, dry, perpetually easygoing P.I. Philip Marlowe in 1973’s The Long Goodbye,” spies The New Republic.

READ MORE: Russian Doll’s Mind-Bending Leaps Through Time (The New Republic)

It’s a perceptive analogy since, in speaking with The Hollywood Reporter, Lyonne says that she and Rudolph are both Robert Altman obsessives.

“The thing that people might not know about myself or Maya is that we have this aesthetic of ‘70s cinema as a state of mind. I just think we have a real shared perspective on the things we love or want to give our attention to.”

READ MORE: Natasha Lyonne on Her Ride to ‘Russian Doll’ and Telling Her Own Stories (The Hollywood Reporter)

She loaded the show with visual references to the auteur cinema she reveres: Cassavetes’s A Woman Under the Influence, Coppola’s Dracula, Cronenberg’s Videodrome, and attributes the Dutch angles in one episode to Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil, and a long tracking shot through a morgue in another to “Spike Lee dolly tricks.”

“The entire season is an Easter egg,” she says to The New Yorker.

Perhaps as a consequence, The New Yorker concludes, the season is more shambolic than the first. “As Nadia’s adventures expand into multiple time lines, the story becomes disorientingly twisty. The result is less a puzzle box than a messy metaphysical punk opera, for worse and for better.”

READ MORE: In “Russian Doll,” Natasha Lyonne Barrels Into the Past (The New Yorker)

Nominated for the 2022 Emmy Award for Outstanding Cinematography for a Single-Camera Series (Half-Hour), cinematographer Ula Pontikos, BSC breathes life into the past of Nadia Vulvokov (Natasha Lyonne). The episode that earned her the nod, “Nowhen,” introduces the time travel dynamic that will shape the course of the story throughout season two.

Equipped with the Sony Venice digital cinema camera, instead of the RED digital camera DP Christopher Teague used in Season 1, Pontikos shares with IndieWire’s Erik Adams and Chris O’Falt why she believed each decade needed its own specific lens:

“For the second season of Russian Doll, we take an audacious leap into time travel and the metaverse as the show delves into Natasha Lyonne’s character’s past. The timeline jumps from 2022, 1980s, 1960s and then to 1944,” she says.

“We conceived of each decade as having an individual tone and the lenses were essential to making it happen. For the 1980s New York, we chose Baltars and Varotal Zoom. They create amazing bokeh and offsets the clean look of Leitz Summilux-C, which were the lenses that we chose for the modern timeline. We used Super Baltars for the 1940s. Venice 6k gave us shallow depth of field and a larger sensor. Period elements were shot on a deeper stop with 4K resolution to maximize the impact of time travel and demands of the final delivery.”

READ MORE: Emmys 2022: Cinematography Nominees on How They Shot the Year’s Best Shows (IndieWire)

Through Animal Pictures, Lyonne is currently developing shows with several female creators, including Alia Shawkat and the Russian Doll writer Cirocco Dunlap. She compares her friendships with other women in the business to the fellowship among such men as Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, and Paul Schrader in ‘70s Hollywood.

“It’s almost like they had a pickup-basketball-game community of filmmaking, where they came around and saw each other’s stuff.”

For Russian Doll, she credits Netflix and Universal for allowing her “to assemble sort of the Avengers of the best lady writers that we can find,” she tells The Hollywood Reporter. “It’s the second time we’ve had an all-female writer’s room. They’re knockouts — such cerebral hotshots. Because it’s a show where we can philosophically wonder: What does it mean to be alive?”

Because of the number of jobs Lyonne holds in the production, the experience is made up of a Russian doll’s worth of perspectives.

“When I’m in the writers’ room, I’m much more of a stressed out person who looks tired and worn down,” Lyonne noted to Variety. “In prep, all of a sudden it’s that person, but with a lot of parkas, because directing loves parkas and sneakers.”

“Then this third character emerges — now I’m inside of Nadia and it’s go time,” she continued. “It’s always such a trip, because at first, I’m feeling out the spaces of her, and then I realize that the joy of the character is there’s so much room to make big and small choices. And then, in the edit, this hobgoblin emerges who just lives on Sweetgreen.”

READ MORE: Natasha Lyonne Explains Why She Loves Conducting the ‘Crazy Train’ of ‘Russian Doll’ Season 2 (Variety)

Want more? Listen to NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour with Mike Katzif and Aisha Harris as they discuss season 2 of the hit Netflix series, including its treatment of intergenerational trauma and how we grapple with the past.

“Really, what this show is about is connection and grappling with the past,” Katzif comments:

“And I think so many movies and shows right now are dealing with that because I think we’re sort of at this point where we are sort of wondering to know, like, what are our connections to how we got to where we are? Whether that’s historically or personally, I think there’s this searching feeling that we’re having where we feel, like, a little untethered. And so these kind of shows, I think — or movies — allow us to grapple with that history, to kind of get into our own psyche a little bit ourselves and wonder, how do we be present right now? Natasha Lyonne has sort of spoken about how this show, in its second season, where the first season was sort of them embracing life again, in some ways, this is sort of like, now that you’re here, what are you going to do with the time that you have left?”

Listen to the full episode in the audio player below: