“Saw X presented the dual challenge of needing to uphold the franchise’s established familiarity while also venturing to introduce the story in a new, thrilling way,” says director and “franchise stalwart” director Kevin Greutert.

He adds, “I also wanted to overturn and have fun with the tropes of the Saw series while taking care not to disappoint those who have long loved these movies.”

DP Nick Matthews brings the fun and a fresh perspective to the Mexico City installment, while honoring what Greutert calls the “sacred iconography” surrounding John Kramer and the Saw world.

“There’s a bit of an expressionism, and some, you know, camp and humor” to the Saw franchise, Matthews explained to Screen Rant.

“I want to try to find what’s beautiful in the brutality,” Matthews told American Cinematographer’s Tara Jenkins.

“I think, ‘How do I take this character and craft something that walks you into that kind of space and into that sort of a world? How do I create shape and darkness within a space?’ For me, it’s about thinking in terms of deep background, midground and foreground, and then letting things fall off in a lot of places.”

John Kramer’s Giallo Inspiration

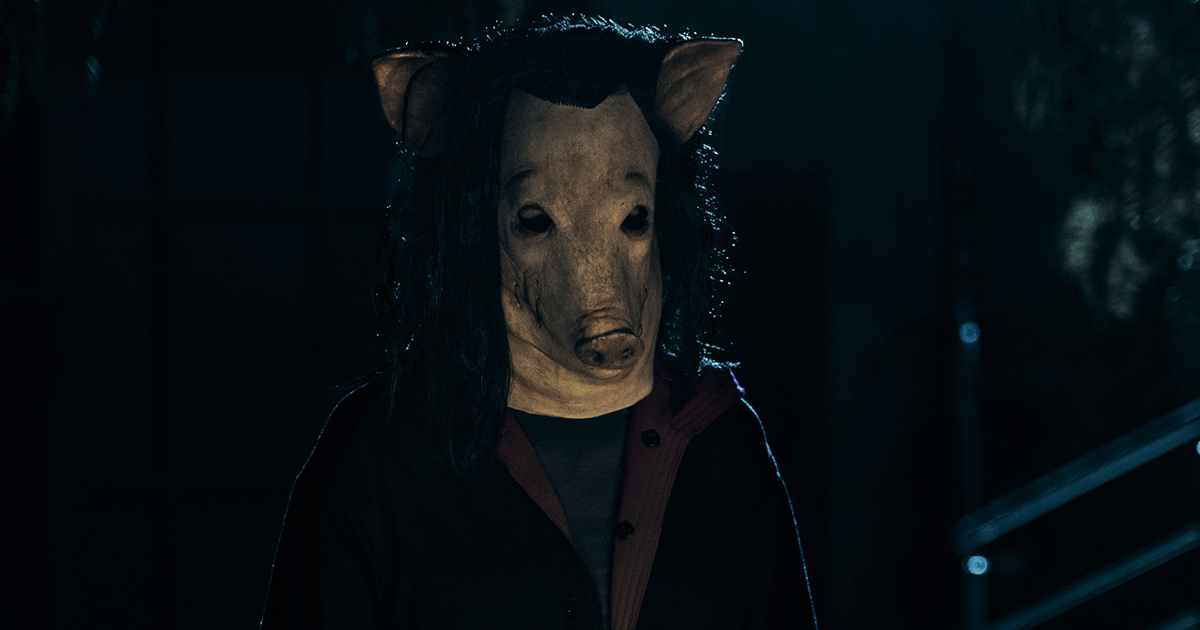

Saw is “very much rooted in Italy’s giallo filmmaking,” Matthews explains. To achieve this look in Saw X, Matthews opted for a Sony Venice, which he rated at ISO 2,000 paired with Cooke Panchro /i Classic lenses and Pearlescent 1 filters, according to Jenkins.

Additionally, he sought to create the giallo look with practical lighting only. He told AC, “We start with whitish-blue fluorescents and golden tungsten lamps. Then we tumble into this dirty palette of sodium-vapor orange, arsenical greens, red emergency lighting, and ochre yellows, all built into industrial fixtures.”

For Saw X, Matthews explains, “I wanted to hark back to the dirtiness, the grittiness, the grime, the pervasive darkness, these poppy giallo colors of the early films, but I didn’t want to do it in a way that felt very heavily done in the DI; I wanted to do it with lighting. I wanted to create three-dimensional color spaces where you have these primary, secondary and tertiary colors populating the film.”

Matthews told No Film School that shooting in Mexico brought “a certain tonal palette to the movie.” But as DP, he says, “I’m trying to design a world that you can walk into and put a camera in and it’ll photograph well.”

Speaking about the colors, Matthews said, “I took the color palettes we used in Mexico and dramatized them for both the abductions because every character who ends up in these traps is abducted in these very giallo-like sequences. Anything that was going to become a tertiary color in the trap sequences I would use as the primary color first — a deep red, or rusty yellow, a sickening green, or a sodium-vapor color.”

Practical Mood Lighting

In addition to setting the mood, lighting was crucial to differentiating between the different challenges, known colloquially as “traps,” that John Kramer poses to those who have wronged him.

“By the time we got into the traps, we were shooting, easily, around 80 shots a day. So, we were lighting fairly 360” Matthews told Jenkins. Because of space and time constraints, “Everything was LED and dressed into practical housings so they looked like they were part of the set,” he says. “However, I’d typically bring a few small instruments out onto the floor like Arri SkyPanel S60-Cs or Asteras to wrap the light further or, in the case of the brain-surgery trap, to add an ochre yellow to the fill side of the character, which dirties up the image and the light.”

An another example, which Matthews shared with Screen Rant’s Grant Hermanns, was “When the emergency lights go off, and we sort of have this big reveal towards the ends, just like, I really wanted the whole room to be bathed in red. And so I remember when I asked the production designer for 50, emergency-like spinners, and he’s like, ‘What the fuck, like, 50.’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah, I need like, one in every corner.’”

READ MORE: Saw X: Traps From the Past (ASC)

Because of the film’s complexity, Matthews told No Film School, “This movie had more interdepartmental conversations than any other project I’d worked on.”

He explains: “Once you get into a trap, you’re dealing with special effects, prosthetics, VFX, production, design, lighting, ultimately, and cinematography. And all of those elements have to come together, costumes as well.”

In addition to complexity, timing was of the essence so that they did not have to reset any of the traps. Matthews recalls to Screen Rant, “All the brain trap stutter-frame stuff was shot on my Blackmagic [6k] just with me, like, you know, walking around while they’re shooting other pieces. And I’m doing it because we just have to move like lightning.”

To achieve the stutter frame look, Matthews employed a “lens whacking” technique, in which “you just connect the lens from the sensor plane, and you’re just kind of playing, which it’s a way to stimulate getting those like film rollouts that they got in the early days of like shooting film and had rollout and then they would use the rollout in the film. And so it’s like playing with light leaks and stuff like that.”