TL;DR

- The Creator was made for $80 million — and looks like $300 million — and Hollywood is astonished.

- Actually shooting on location proved far more cost efficient than studio builds and volume work, not least because of writer-director Gareth Edwards’ savvy with creating VFX of realism and scale.

- The film is IMAX and Super X screen-certified, yet was shot almost entirely on a $4,000 prosumer camera, giving the lie to the idea that blockbusters need have blockbusting budgets and the highest end gear.

In modern film economics, the entire $80-90 million budget of The Creator is usually allocated to marketing a sci-fi blockbuster the scale of Avatar or Star Wars — and Hollywood is marveling at how director Gareth Edwards got away with it.

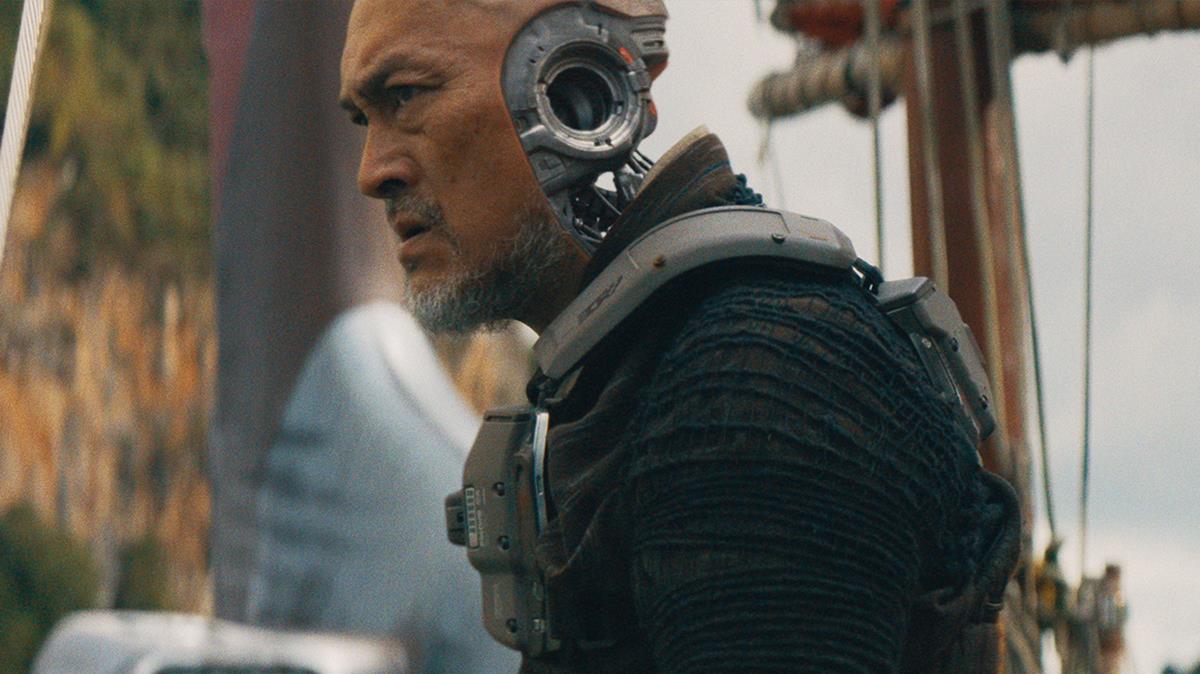

The Creator looks like it was made for double or quadruple the price and would have done had conventional methods been applied. Instead, Edwards reverse-engineered the process by filming with a relatively small kit and crew in multiple locations, locking off the edit, and only then calling in VFX.

“They said there’s no way we can really do this because… you can’t find these locations and build sets in a studio against green screen, and it’ll cost a fortune,” the British writer-director explained to AV Club and commented on by John Owens at Frame Voyager.

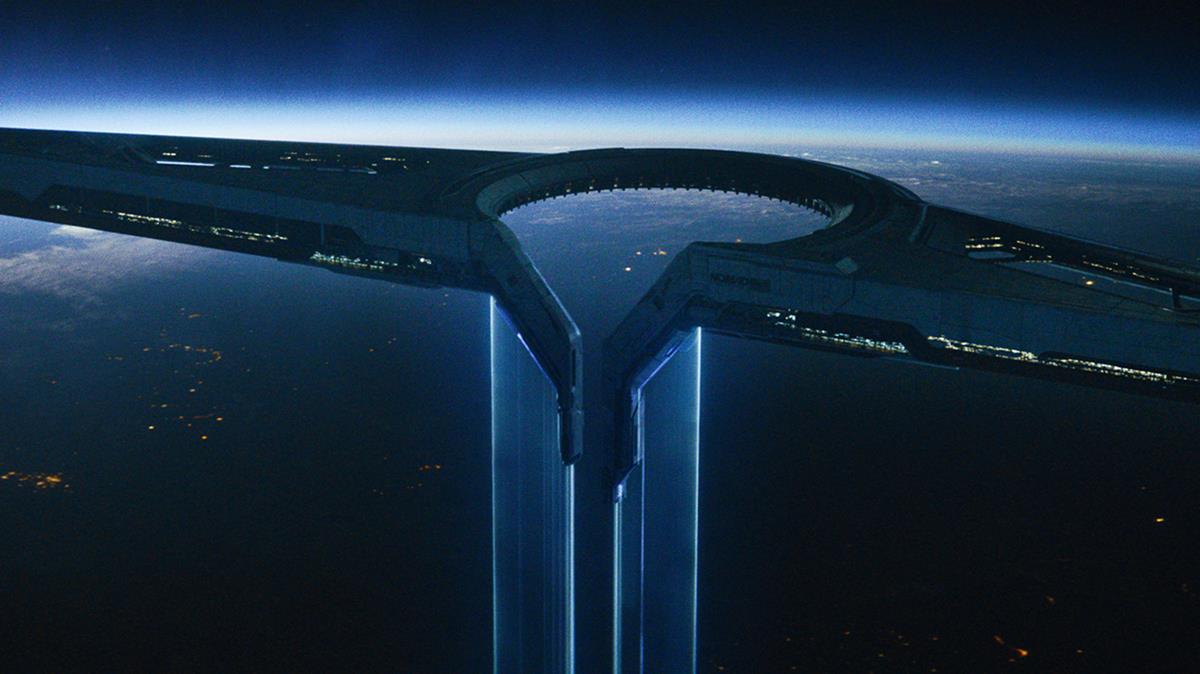

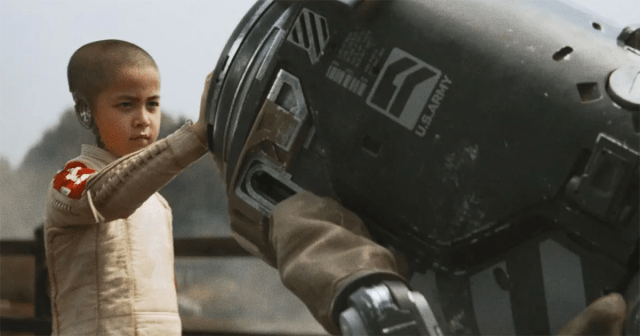

“Instead, we went to real parts of the world that look closest to what we wanted, then afterwards when the film’s fully edited, we get production designer James Klein and other concept and VFX artists to paint over those frames and put the sci-fi on top.”

Edwards spent a decade at the start of his career, “doing computer graphics very cheaply in my bedroom,” Edwards explained in the same video breakdown. “I tried to learn a lot of tricks as to how to make things look bigger than they are with very little effort. Like one of the things that’s free [to build] is scale. You learn that something’s only big when it’s relative to something else. The key is always having this something else in the frame.”

With Todd Gilchrist at Variety, he adde, “Essentially, if you make sure everything in the immediate 10 or 20 meters [of the frame] is for real and that the stuff that you’re going to invent is in the distance,” he says. “The way parallax works, the brain can’t tell motion beyond about 20 meters. It’s like putting digital matte paintings behind your foreground. That’s a really good bang for your buck.”

The shooting process could really only be called guerilla filmmaking, with Edwards taking cues from his original low budget feature Monsters.

One of the most indie methods he opted for was a rejection of how VFX is normally approached in the industry today, which is to use green screen and volume stages and to push iterations of VFX up to minute before release.

What was unorthodox was the locations did much of the visual heavy lifting with environments, lighting, architecture and geology for the most part looking just as they were filmed. Only after the film was edited and locked was VFX allowed to go to work.

“There was a little bit of volume work at Pinewood but very low,” Edwards admitted to Owens. “And if you do the maths, if you keep the crew small enough, the theory was that with the cost of building a set which is typically like $200 grand — you can fly everyone anywhere in the world for that kind of money.”

Numerous VFX houses were contracted to work on The Creator, including ILM, Folks VFX, Outpost VFX, VFX Los Angeles, and Misc Studios, among others.

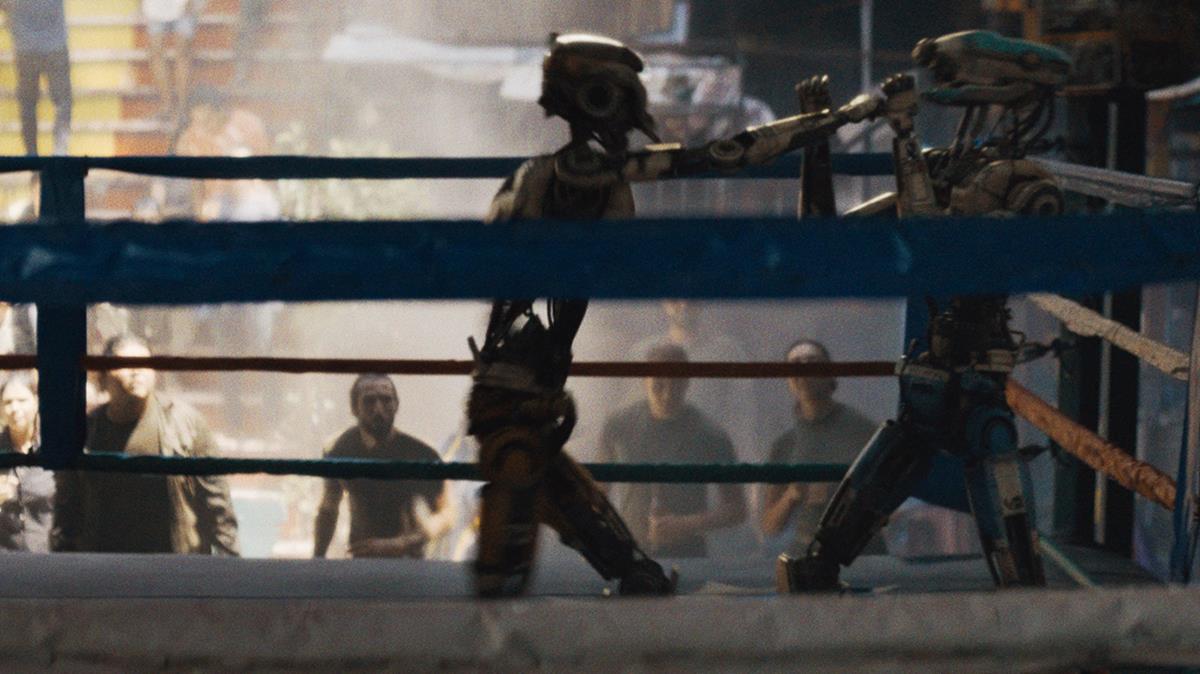

“We’re not saying that there wasn’t work done with the backgrounds, but VFX are not having to be fully digitally recreate every scene. This allowed more effort to be put into making the robots of this world feel even more real [because] locations, props and characters are already in the shot. Often there was no additional work or relatively minimal labor needed in finalizing a character or environment.”

According to Edwards, this approach saved them tens of millions of dollars and stands in contrast to the way CGI and VFX heavy productions are made.

To illustrate the indie nature of the shoot, Edwards says a scene near the beginning when Joshua (John David Washington) was running down the beach under crossfire was shot in a location still open to the public.

“We didn’t close that beach. If you look at our feet in the background, you can see bars and tourists. One person came over, and was like ‘What are you doing?’ because it was just the four of us with a camera running around and it didn’t look like this big massive movie.”

Concept Cinematography

The Creator’s original cinematographer was Greig Fraser (The Batman), before he was lured away by the mega-budget Dune (for which he wound up winning the Oscar).

Before launching the production to shoot on location across the globe, Edwards filmed a proof-of-concept reel, in which he captured actors and extras in real environments without preparing them in advance to accommodate digital replacement technology.

“We wanted to do it not in a traditional system, and it was really important that we stuck with that, because sometimes in filmmaking you make small compromises, and before you know it, your small compromises become big compromises,” Fraser said in Variety. “So we worked for a number of years just doing testing and talking and looking at the way we could actually achieve this.”

He elaborated on working the concept through with Edwards in The Playlist: “We try to keep the camera-facing crew as small as possible, allowing for those resources to be put into areas that need them later on, like post-production or VFX.

A lesson I’m hoping everybody who’s reading this will learn is this: it’s possible to completely turn the filmmaking process on its head, and when we do, there are massive cost savings to be done, but also quality improvements.

“Films work because every person knows the parameters of their job, and that’s why you don’t have people stumbling over each other. It’s an established relationship; it’s efficient from a personnel standpoint, but unfortunately, with those efficiencies also come inefficiencies that we’ve hopefully turned on their heads with this movie.”

Unusual Camera Choice

Equally as unusual was their choice of a prosumer mirrorless camera, the Sony FX3.

“It’s a camera you can buy at Best Buy,” Edwards says. “It looks like film. It’s full frame, full IMAX resolution [for certification on IMAX screens], and has filmic photographic quality to it.”

Gray Kotzé at IndepthCine went deeper on the camera choice, explaining that the difference between the $3,900 Sony FX3, and a $75K Alexa Mini is remarkably small.

The FX3 can record in 4K resolution, while the Mini LF can do 4.5K. In terms of dynamic range, Sony reports 15+ stops, while ARRI claims 14+ stops. When it comes to bit depth, the FX3 shoots 10-Bit 4:2:2 internally in SLog, whereas the Arri can shoot 12-Bit 4444 XQ in Log-C.

“While the ARRI does outperform the Sony visually, especially in the color department, the point remains that the gap between them is pretty slim, when comparing a prosumer and a professional camera and seems to be closing more and more every year.”

Does this spell the end of the Alexa forever and mean that all future Hollywood productions will use the FX3? Well, no, probably not.

Kotzé thinks the workflow and philosophy of using high end camera gear is too ingrained.

“The entire industry is set up around working with high end production cameras and I don’t think that this will change any time soon,” he says.

“Studios know what they will get when shooting with an Alexa, and producers are used to budgeting for gear in terms of an Alexa rental fee,” he says.

However, what we may see is that features from prosumer cameras — such as its high ISO base and smaller form factor — filter into the higher end cameras. And that this prosumer gear will increasingly be adopted across lower budget projects.

Questions Over One VFX Shortcut

Shortly after the trailer released allegations emerged, that the filmmakers had used footage of a real life explosion in Beirut 2020 as the basis for a shot when a nuclear warhead detonates on LA.

It’s not unusual to use original source material, stock footage for example, in the VFX pipeline but it’s not clear if this instance — which killed hundreds of people — was used in oversight.

“While The Creator’s team favored more practicality and realism over excessive the effects, this is one instance of realism that they went a little too far in using footage of a real life tragedy, especially a recent one for a purely fictional movie. It seems a little bit out of touch, to say the least and it proves that we may need more discussion when it comes to this side of digital effects in the future.”

Edwards doesn’t appear to have addressed this anywhere, but Owens does and condemn its use.