The use of long takes can be exhilarating for viewers as much as for the cinematographer and director choreographing the shots, but there has to be a good narrative reason or it can distract (or bore) the audience.

A successful long take should transport the viewer to at least one emotional destination: setting, character or plot, according to Studio Binder.

“The really good ones will have elements of all three,” the studio suggests in its step-by-step guide.

“Long takes are big, home run swings. Connect… and your scene becomes robust, seamless, masterful. Miss… and your scene becomes derivative, self indulgent, or worse… unmotivated.”

READ MORE: The Best Long Take Shots & How They Push the Story Forward (Studio Binder)

There is no set formula for the “one-take” shot other perhaps its suitability to propelling the plot, immersing the audiences or evoking an emotional response.

Alfred Hitchcock was among the first directors to experiment with the idea. In Hitchcock’s single set studio bound murder mystery Rope (1948) he staged scenes to last for the duration of the 10-minute film reel, masking cuts by having the camera move behind furniture or an actor’s back.

Similar tricks can now be done digitally, with first Emmanuel Lubezki for Birdman (2014), then Roger Deakins winning the Best Cinematography Oscar for 1917 (in 2019), both filmed as if in one shot. What was remarkable about 1917 was that the camera was designed to be travelling at all times with the characters through different landscapes and locations, never returning to the same place.

Aside from Deakins and director Sam Mendes, editor Lee Smith should receive more credit than he perhaps has for helping the team judge the pace of the story beats and deciding when and how to transition between cuts.

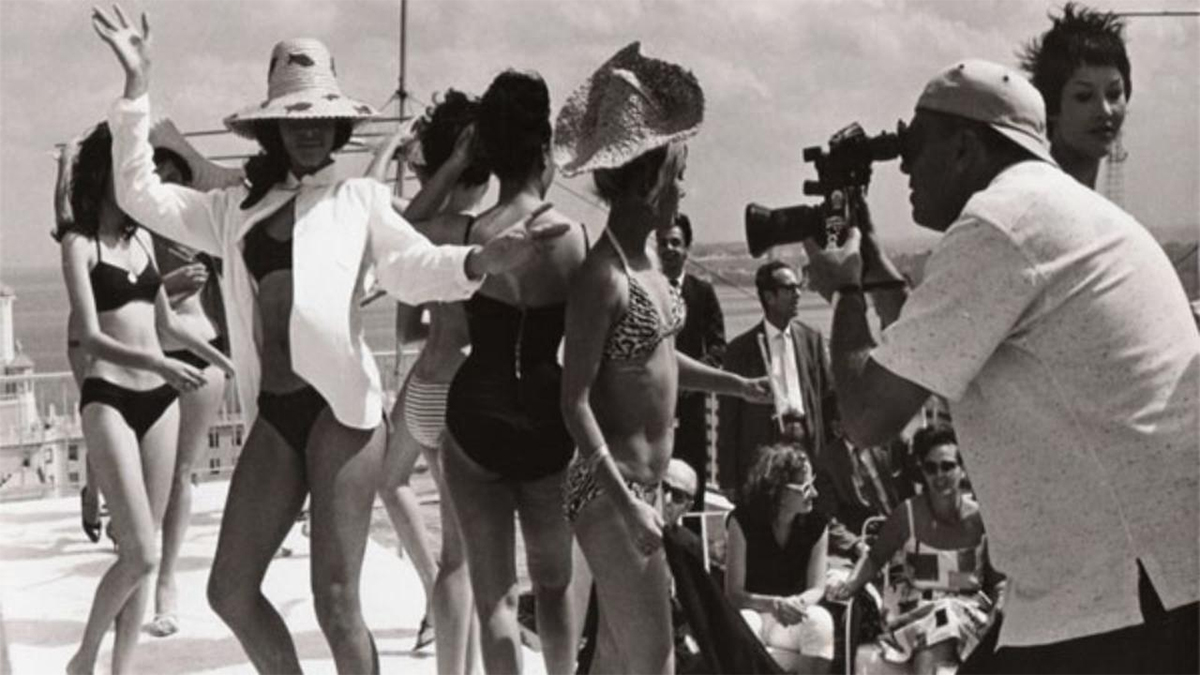

In 1964, Soviet propaganda film Soy Cuba featured a remarkable opening sequence in which cinematographer Sergey Urusevsky’s camera travels up an elevator to the rooftop of a Havana casino, takes in guests being served cocktails before plunging into the swimming pool to swim with them.

The development of Steadicam in the 1980s revolutionized what was possible by freeing the camera to move away from the dolly and crane and therefore through doorways, into cars, down stairs.

READ MORE: The Astonishing Images of I Am Cuba (American Cinematographer)

The Copa Shot from Goodfellas is a prime example and one of the few shots in the history of cinema readily identifiable by name. It features Ray Liotta leading Lorraine Bracco — and by extension the audience — through the back entrance of New York’s legendary Copacabana nightclub as Steadicam operator Larry McConkey glides along behind them.

READ MORE: Steadicam Operator Larry McConkey on Filming the Goodfellas Copacabana Tracking Shot and The Early Days of Steadicam (Filmmaker Magazine)

READ MORE: ‘You Just Have to Accept That Wes Is Right’ The French Dispatch crew explains how it pulled off the movie’s quietly impossible tracking shot. (Vulture)

For The French Dispatch, Wes Anderson’s anthology of short films about a Sunday newspaper supplement, Anderson’s long-serving key grip, Sanjay Sami, explained to Vulture that the director didn’t want to use the stabilized rig on the film’s final segment, “a quietly impossible 70-second tracking shot… the most complicated shot I’ve ever worked on in my life.”

The entire scene following Jeffrey Wright’s journalist Roebuck Wright through various rooms of a police station unfolds in a single continuous motion. On dolly tracks.

“There is a level of exactness to Wes’s dolly shots that cannot be achieved with a handheld camera, even a Steadicam,” said Sami, adding that Anderson “wanted to put his camera on rails to shoot it and have that camera do things that a camera on rails can’t do — like zigzag at high speed, and at precisely 90-degree angles, at four different junctures in the shot.”

The camera moves laterally, seeming to pass through walls as it follows the narrator through the building, then suddenly shifts direction at a right angle in order to walk in front of Roebuck, then resume lateral motion again, then do another right-angle move.

Co-producers Olivia Peissel and Jeremy Dawson credit Jeffrey Wright with the decision to recite the story within the tracking shot.

“It’s an act of incredible boldness and confidence, shooting the scene the way Wes shot it,” Wright said. “He turns the police station, a place that tends to be inhospitable to men such as himself, into a set, almost a playground, that Roebuck Wright is completely in control of.”

Watch This: Wes Anderson’s Amazing Long Shot From The French Dispatch

READ MORE: ‘You Just Have to Accept That Wes Is Right’ The French Dispatch crew explains how it pulled off the movie’s quietly impossible tracking shot. (Vulture)

Also regularly making the lists of most top cinematic “oners” are Joe Wright’s staging of the Dunkirk invasion in Atonement (2007); the brutal hammer fight scene in a corridor of Chan Wook-park’s Oldboy (2003) which probably owes a debt to John Woo’s Hard Boiled (1992), in particular the bloody hospital shootout and the car chase in Alfonso Cuaron’s Children of Men (2006) where the main characters (including Clive Owen and Julianne Moore) are stopped by an angry mob.

For my money one of the best is also the most subtle. In fact, the viewer will barely notice it first time around, so compelling is its use in honing in on a crucial plot development.

In All The President’s Men (1976) Gordon Willis’ camera moves imperceptibly closer from wide to close-up on Bob Woodward as he scoops intel on the phone.

In lesser hands the director would have cut the scene using coverage but Alan J. Pakula holds on the shot as Woodward (Robert Redford) takes notes from a couple of phone calls and trusts the audience’s attention to be zeroed in trying to listen to what the caller is saying, while the camera blots out background movement.

Collider included the take in its list of 22 all-time favorites, but clocks it at six minutes. I think it may be over 12 minutes, making Redford’s performance all the more exceptional. Its brilliant either way.

READ MORE: Settle In, Here Are 22 of the Most Unforgettable Long Takes in Movie History (Collider)

In theaters at the end of November was a new British movie, Boiling Point, starring Stephen Graham (The Irishman) as a chef at the end of his tether working the kitchen over Christmas.

It’s a 90-minute movie and, unlike 1917, this is one of a rare breed of movie shot entirely in one take without artifice. Others on this list of super-tense film construction are Russian Ark (2002), the dramatized documentary shot in St. Petersburg’s Hermitage museum; German crime thriller Victoria (2015), directed by Sebastian Schipper and filmed in multiple locations including a night club, and Canadian indie Last Call (2019) which upped the ante by filming two 80-minute single takes simultaneously and presented the nail-biting drama in split screen.

READ MORE: Behind The Scenes: Boiling Point (IBC365)

Boiling Point DP Matthew Lewis told IBC365 he aimed to create a constant flow between characters so you never feeling like the camera is wandering by itself; a criticism that could be levelled at Birdman.

“As soon as you notice a camera walking down a corridor trying to find something you get pulled out of the story,” he says. “It was like pinballing between actors to distract the audience from the one take. As much as I want people to be raving about it, I’d be really concerned if they were and not talking about the story.”