TL;DR

- In a world of crystal-clear 4K smartphone videography, the detuned aesthetic of indie horror feature “Skinamarink” is even more distinct.

- Working under a no-budget budget of just $15,000, writer-director-editor Kyle Edward Ball found that micro-budget limitations fueled his creative vision.

- Ball used his short film “Heck” to develop a technique the indie filmmaker calls “filming by implication.”

- This technique demanded a set of steadfast rules: “We never see someone’s face. We avoid showing people on screen for too long. Whatever dialogue is delivered is always delivered off-screen. We never go outside. We never leave the house.”

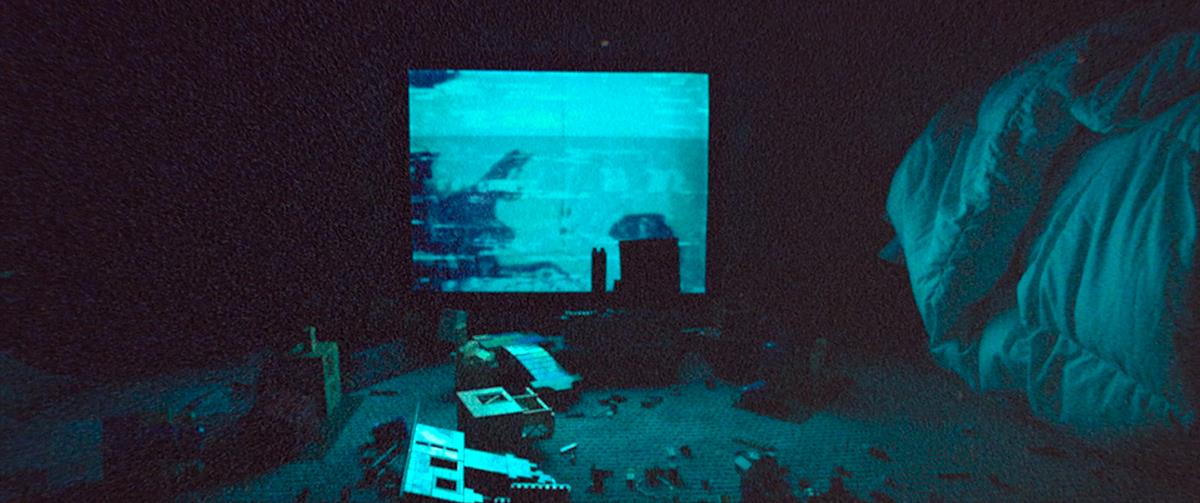

The trailer for Skinamarink shows just how much work was involved in making the indie horror film look so bad. In this world of crystal-clear 4K smartphone videography, a detuned aesthetic is even more distinct and perhaps welcome. Writer-director-editor Kyle Edward Ball absorbs any sense of clarity out of his movie, visually or psychologically. This could be down to the no-budget budget (which reached a final tally of $15,000), but in fact proclaims the skills of the indie filmmaker and his small crew.

Skinamarink has been acquired by horror streamer Shudder and is currently in theaters via IFC Midnight. It will debut on Shudder later in 2023.

Filmmaker Magazine’s Natalia Keogan describes the incredibly loose narrative. “It follows young siblings Kevin (Lucas Paul) and Kaylee (Dali Rose Tetreault) as they patter around their family’s strikingly ordinary middle-class house in the dead of night circa 1995,” she writes.

“Their parents are nowhere to be found, all of the doors have mysteriously vanished and the lights eventually stop working. While this phenomena is enough to chill any child, their well-being is most threatened by a supernatural presence that beckons the siblings to obey increasingly disturbing requests.”

Keogan’s description continues in nightmarish terms: “Skinamarink does not rely on typical genre conventions, barely even showing the protagonists in full, opting for shots of disjointed limbs and obscured faces. The film’s bone-numbing terror comes from somewhere deeper and more genuine than a cheap jump-scare, like an early childhood nightmare extracted from our collective subconscious, transferred to a VHS tape and screened on an old CRT television set at three a.m.”

READ MORE: “Significant Portions of the Movie Were Literally Just Lit by the Television”: Kyle Edward Ball on Skinamarink (Filmmaker)

In his interview with Ball for Roger Ebert, Isaac Feldberg was keen for the filmmaker to unveil his production techniques. “Ball found that micro-budget limitations fueled his creative vision, necessitating all manner of trick photography and unconventional angles to mimic a child’s-eye view.”

His short film Heck was a proof-of-concept exercise for what was to come. “Through doing my YouTube series, I developed a technique of filming by implication, instead of showing. So, instead of showing actors, I was doing point-of-view shots or filming different parts of the room while we had audio off-screen. And, after a while, I thought, ‘Maybe I could do a feature like this…’”

Ball also detailed some of his steadfast shooting and framing rules, a practice not uncommon in episodics. “I set rules in place that I wasn’t allowed to break. We never see someone’s face. We avoid showing people on screen for too long. Whatever dialogue is delivered is always delivered off-screen. We never go outside. We never leave the house. We’re always in the house.”

With those visual constraints in place Ball looked to the audio to seal the horror. “I didn’t just want Skinamarink to look like an old movie,” he told Feldberg. “I wanted it to feel and sound like one. I wanted to go really [hard] with that. I didn’t just want to make the dialogue sound like it was recorded on an old microphone. I wanted the audio to feel like an old, scratched-up re-taping of a film that wasn’t preserved from the ‘70s — lots of hiss, lots of hum.”

READ MORE: The Internet Has Been My Co-Director: Kyle Edward Ball on Skinamarink (Roger Ebert)

Ball’s idea for the visuals was to shoot as near to darkness as possible and then grade to further distress what he shot with his DP Jamie McCrae. He explained to Lex Briscuso at Inverse how they created the look. “When I was doing my YouTube channel, I was also gravitating toward the lo-fi look. I thought ‘Why can’t I make a movie like it’s from the ‘70s? Or the ‘50s? The ‘30s?’ It evolved into, ‘What if I did an entire movie in this style?” So I started writing my script,’” he said.

“Working with my amazing director of photography, Jamie McCrae, I said, ‘OK let’s get a really good camera that’s really good in low light and see if we can just use practicals.’ I set some rules for myself. We can only use practical lights: flashlights, light coming off a TV, a lamp.”

Another big issue were the scenes set in pitch black, Ball told Briscuso. “Obviously, we couldn’t shoot 100% pitch black unless we used infrared, so we developed this technique of putting a sun gun on top of the camera, putting a blue filter over it, and grading with it,” he said.

McCrae selected the Sony FX6 as the main camera, Ball recounted, adding, “I forget what lenses we used, but the great thing about a modern digital camera — and that one in particular — is that it almost sees in the dark, almost better than the human eye, with somewhat minimal artifacting or grain.”

But when Ball reached the post-production stage, he discovered that he couldn’t edit the film and then age the material after the fact. “I had to do it in tandem,” he told Briscuso. “The mood is so intrinsically tied to the lo-fi aspect of it that it was impossible. So I did it step by step; that’s really why the editing took four months.”

To make the footage appear old, Ball employed a package of 16mm film grain overlays he already had on hand. “In editing, I picked different overlays, graded and played with the levels shot-by-shot, and I just did that until it looked right and read well. It wasn’t just one overlay I looped a hundred times. I took my time to make sure there were enough varieties, so you didn’t subconsciously say, ‘Oh, I’ve seen this overlay before.’

“As far as the special effects, a lot of it was just simple old Hollywood tricks that you can get away with if you’re using a layer of grain over it. There’s a few parts where things appear on the ceiling, floating. That was literally just me holding it up and photoshopping myself out. The doors and windows, I just Content Awared them out.”

READ MORE: Skinamarink Director Kyle Edward Ball Knows What Haunts Our Nightmares (Inverse)

Sam Theilman‘s review of the movie for Slate is perhaps the most discerning, “I think Skinamarink is the first movie I’ve seen that is shot in such a way as to show only what its child protagonist can understand. I can’t imagine another film doing this successfully, or even wanting to see this particular film again, but it’s a remarkable achievement,” he writes.

“It evokes the nameless dread of barely verbal childhood so thoroughly and uncompromisingly that it remains frightening long after it ends, not because it forces us to question the rational world, but because it makes us remember a time before we could understand anything at all.”

READ MORE: A Blair Witch–Style Horror Sensation Captures the Essence of Childhood Fear (Slate)

Variety’s William Earl has the scoop on what’s next for Ball. “He’s currently kicking around two ideas that both sound like a logical extension of Skinamarink. One is a take on the Pied Piper legend, the other about three strangers who all see the same house in a dream.”

READ MORE: How ‘Skinamarink,’ a $15,000 Horror Movie, Became the Internet’s New Cult Obsession (Variety)

Next, Watch This:

LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION! SPOTLIGHT ON FILM PRODUCTION:

From the latest advances in virtual production to shooting the perfect oner, filmmakers are continuing to push creative boundaries. Packed with insights from top talents, go behind the scenes of feature film production with these hand-curated articles from the NAB Amplify archives:

- “Decision To Leave:” Park Chan-wook’s Love Story/Detective Story

- Fantastic Fantasía: Making Alejandro González Iñárritu’s “Bardo”

- “The Banshees of Inisherin:“ Martin McDonagh Tells a Wonderful/Terrible Tale

- Control and Chaos: Todd Field on “Tár”

- Family Pictures: James Gray’s “Armageddon Time”

- She Stoops to Conquer: Gina Prince-Bythewood Goes to War for “The Woman King”

- The Revolution Will Be Televised: Making the Immersive, Explosive “Athena”