“There was a period early in the pandemic when directors Neill Blomkamp and Ben Wheatley wondered if they might not have jobs anymore. At least not in film.

“Both Wheatley and Blomkamp responded to the possibility that the film industry might be snuffed out… by making films. Wheatley’s In the Earth, which he wrote and directed, takes place largely outdoors, a concession and response to COVID-19. The pandemic-set horror movie follows a scientist (Joel Fry) who ventures into the woods with a park ranger (Ellora Torchia) in search of a colleague.

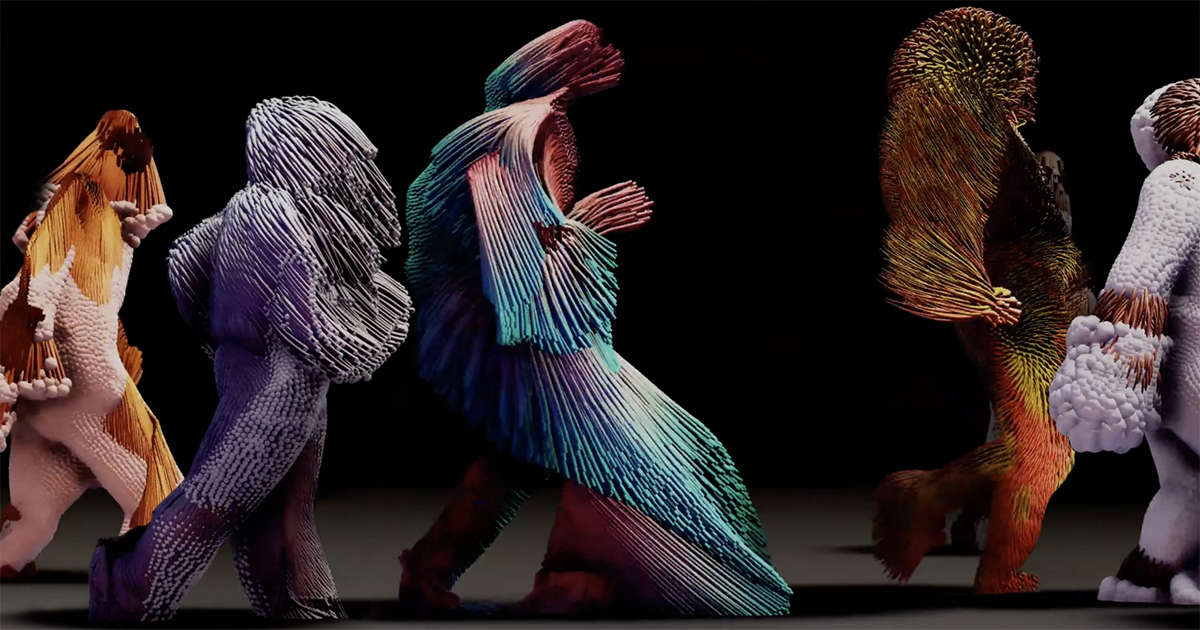

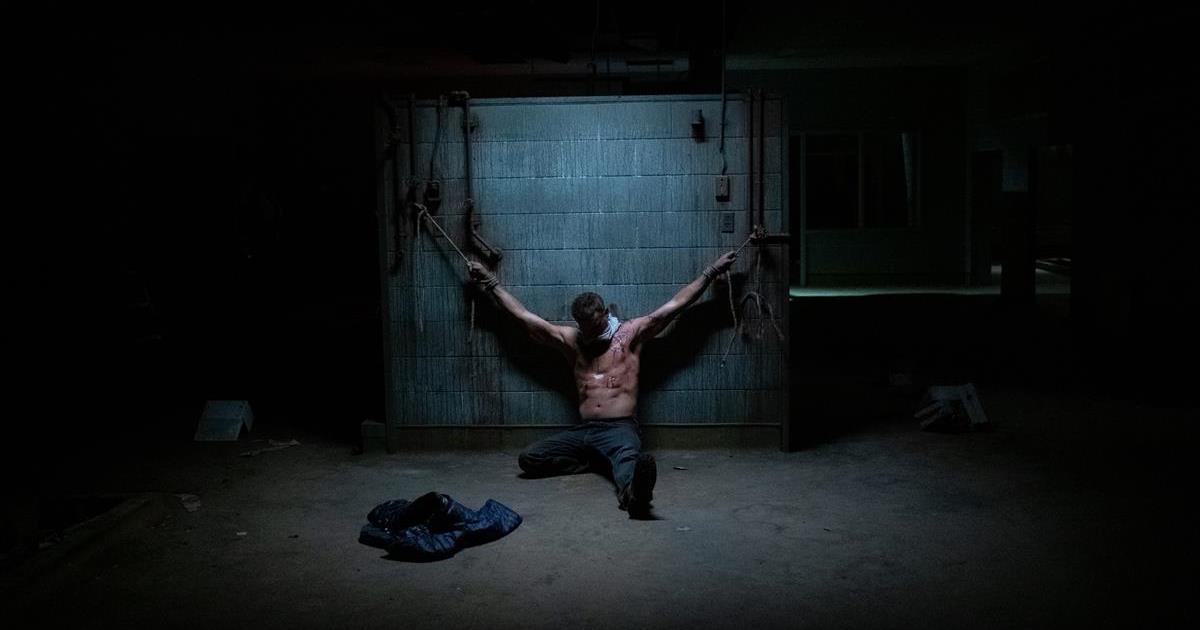

“Blomkamp’s Demonic, his first feature film since 2015’s Chappie, is about a woman (Carly Pope) who is able to communicate with her murderous mother (Nathalie Boltt) through extraordinary new technology. The film uses an optimal technology called volumetric capture that is similar to LIDAR (light detection and ranging) to illustrate the virtual, eerily realistic world where they meet. Blomkamp did it through Unity, a platform by Unity Technologies often used to develop video games, and Wheatley sees it as an extension to the ‘bullet-time’ of The Matrix.”

Source: Tim Molloy, MovieMaker Magazine

AT A GLANCE:

MovieMaker Magazine’s Tim Molloy spoke with filmmakers Ben Wheatley and Neill Blomkamp in a wide-ranging conversation that covered everything from the speculative fiction of Neal Stephenson to Archillect, an AI that seeks out visually stimulating content.

The filmmakers also discussed how the COVID-19 pandemic shaped their approaches to their craft. “In the Earth was clearly a reaction to the pandemic,” Blomkamp says of Wheatley’s latest film.

“I started writing it within the first week of the lockdown,” Wheatley responds. “I don’t know how you felt, but I felt like I might have retired — or been forced into retirement — within that first couple of days. I sort of thought, there’s no job for me anymore. … I was gonna get a mohawk and then get my crossbow out. It felt like it was the end of my job.”

Blomkamp doesn’t disagree, pointing to the differences between his latest film project and his previous work, such as District 9. “I definitely felt, when things were at a fever pitch, it wasn’t really clear exactly what path the film industry or entertainment at large would take,” he said:

“I think Demonic was slightly a symptom of that in the sense that I just wanted to shoot something that I knew I was able to do, because it was mostly self-financed. … And then AGC Studios came on board and kind of doubled our self-financed budget. So we had a bit more cash. But the computer-graphic simulation stuff was always there. We just moved into being able to shoot it more narratively in a traditional sense. It was less found footage as an approach. Yeah. But it still is one-thirtieth or one-fifteenth the size of the other films I’ve done.”

Blomkamp also discussed the use of volumetric capture, also known as lightfield, or computational cinematography, in Demonic. “The system of capture was highly unique,” he said, describing how it was created using the Unity platform. “Instead of motion capture, where you’re assigning the motion or facial capture that we gather from an actor onto a 3D avatar, this process was really turning the video files from multiple cameras into geometry. Which is like LIDAR. … It’s 24 frames per second of individual bespoke pieces of geometry, with textures on them.”

Referencing The Matrix movies, Wheatley calls volumetric capture “the next step from bullet time, basically.” But with it’s grainy, blobby look, Blomkamp isn’t sure lightfield capture is ready for prime time.

“I don’t think that volumetric capture is at the point that you could use it unless narratively it was justified — in a way that it felt like some sort of low-resolution world that you were going into,” he says. “So there almost is no other way to use it. I think you’ll see it everywhere in films 10 years from now, but that will be at the point that individual hair strands are visible.”

Head over to MovieMaker Magazine to read more.