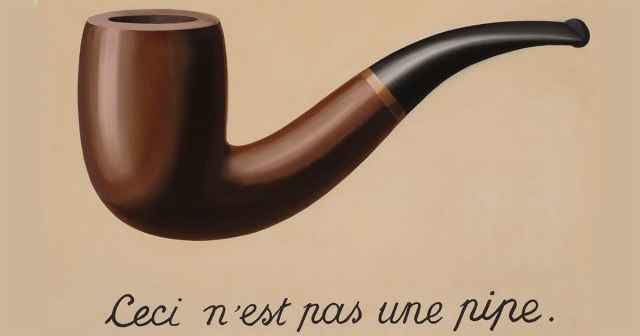

If there’s one thing that media and Big Tech can agree on when it comes to AI, it’s that existing copyright laws are outdated and in need of an upgrade.

There’s a gray area being fought over in the courts by artists like Sarah Silverman versus companies like OpenAI over the definition of “fair use.”

Lawyers for Big Tech might be able to pull this line of attack apart by showing that their large language models are not copying copyrighted works at all.

Others, like media and legal expert Peter Csathy, argue for a trickier to define case that it is ethically right to reward artists and that doing so is in the interests of the public good.

“It’s not about anti-tech, or pro-big media, it’s about taking the value that’s been created by new GenAI models and recognizing the contribution made by creators in the first place,” Csathy said during a debate with tech entrepreneur Robert Tercek on The Futurists podcast. “It’s about sharing in the pot of the opportunities in some kind of equitable fashion.”

A central issue is the unauthorized use of copyrighted content by AI companies to train their models. Major media entities like The New York Times have filed lawsuits against AI firms such as OpenAI and Microsoft, arguing that their copyrighted content has been used without permission, undermining the creators’ rights and economic interests.

Csathy argues that AI’s reliance on copyrighted content necessitates fair compensation for creators. He said the use of AI to generate content raises concerns about the loss of control and the potential devaluation of creative works.

His argument is that Big Tech, notably OpenAI, has gotten rich — billions of dollars worth of market capital rich — because its models have been trained on millions and millions of pieces of copyrighted works.

It’s only fair then for a licensing fee to paid to creators by developers of LLMs for use of their copyrighted works.

“The reality is that no generative AI would have any value whatsoever it unless it was ingested with copyrighted creative works. That’s what gave it value,” Csathy says.

He believes the outcome of the copyright lawsuits brought by the likes of Sarah Silverman and The New York Times against OpenAI and others will result in some kind of opt-in or opt out system “where a creator can decide whether they want to their work to be available to be licensed.”

With 500,000 open-source models available today, such a forensic tracking and payment system would need policing at a global level but Csathy doesn’t think that problem insurmountable.

“The goal is to create a system that is more equitable system, that can be such so much better for the end user that they will gladly pay something to use that rather than something that’s just free.”

Even if a new compensation scheme were agreed between Big Tech and creators going forward, Csathy questions the “billions and possibly trillions of dollars of value” in generative AI that have been already been accrued without compensating artists.

“It’s about money. It’s about control and it’s about respect for the artists. And part of being an artist is that you have control, over your creation.”

Playing devil’s advocate, Tercek laid out some of the defense that Big Tech will use to justify training on copyrighted work as “fair use.”

It’s an interesting argument, and goes like this:

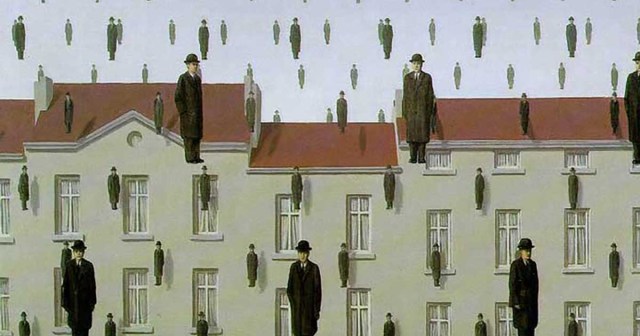

“The AI reads all the books, or looks at all the images, or listening to all the music and then that model begins to build parameters. A big question about this is, is it fair use? Is it okay to look or read or listen? There is no law that prohibits reading a book. There’s no law that says, You can’t learn by looking at a picture.”

Tercek explains that what the tech companies will insist on is that they do not retain any copies they are reading, or in case of pictures, they are looking at images, in the case of music, they’re listening to. These are mathematical representations only.

“Once the LLM is trained, is just a mathematical representation of what they call ‘parameters.’ These are different values that are set based on looking at a lot of Van Gogh pictures for example. They start to arrive at kind of a extrapolation. There’s a pretty strong argument to say that all they’re doing is measuring facts. Facts like what kind of values and colors and hues does Van Gogh use.

It’s not replicating any of Van Gogh’s paintings but we have millions of incredibly precise, measurements about his paintings. Those are facts and facts can’t be copyrighted. What we can recreate in LLM is a factual representation of all those different values that go into creating that work.”

Further, he says that the cases brought by The New York Times and other artists against Big Tech are antiquated because copyright law needs updating to account for the age of AI.

Tercek argues that original copyrighted works like films or books or painting are “fixed works delivered in fixed media.”

“What LLMs are doing is transforming those fixed works into something that is participatory, that billions of people can interact with to build new creative things,” he says.

“So should the artists who created the original work get paid a royalty off of those things? These are huge open questions right now. But this notion of a fixed work that is copyrighted for a century because that’s what we have right now is an absurdly distended copyright term today.

“Maybe that notion is going to change and maybe what media has to turn into is something that is more open, more participatory, something that enables audiences to actually play with and mess with and participate in meaningfully.”

On this point Csathy agrees. He thinks it’s a massive opportunity for artists — so long as the artists themselves want to be a part of it. “They should have control of whether they want to enable their fans to build on top of their work. If they do, there’s a whole new opportunity.”

If they want to take advantage new AI tools that will it possible for anyone to find novel ways to express themselves, with new kinds of mashups, then creators need to get grips with the intricacies of the technology and of new monetization pathways.

“You really need to play with these AI tools, understand them, learn about them, or get people on your team who does understand them,” Csathy advises. “There’s not $100 out there in one bucket — there are little pieces here and there and everywhere. You’re delighting your fans more and maybe getting a chance to be closer to them.”

READ MORE: GenAI in Hollywood: Threat or Opportunity? (Doug Shapiro)

Why subscribe to The Angle?

Exclusive Insights: Get editorial roundups of the cutting-edge content that matters most.

Behind-the-Scenes Access: Peek behind the curtain with in-depth Q&As featuring industry experts and thought leaders.

Unparalleled Access: NAB Amplify is your digital hub for technology, trends, and insights unavailable anywhere else.

Join a community of professionals who are as passionate about the future of film, television, and digital storytelling as you are. Subscribe to The Angle today!