READ MORE: Algorithms Can Now Mimic Any Artist. Some Artists Hate It (Wired)

AI is already so proficient at copying a particular artist’s work it won’t be long before filmmakers need to protect themselves from plagiarism.

There could even be a need right now to copyright camera moves, editing choices, color palettes, lighting schemes, or compositions because there is nothing to prevent an AI from entirely generating a new gangster movie in the style of Martin Scorsese or a sci-fi film that looks and feels like it has come from Stanley Kubrick.

On the other hand, there will be some in Hollywood no doubt calculating that if an AI could perfect a hit movie without having to pay for the fuss, the time, all the micro-decision making and risk that human talent brings it’s a price worth paying.

This is not idle speculation; the debate about artistic infringement by algorithm has become a hot one in the art world.

Swedish artist Simon Stålenhag is among those sounding a warning. “AI basically takes lifetimes of work by artists, without consent, and uses that data as the core ingredient in a new type of pastry that it can sell at a profit with the sole aim of enriching a bunch of yacht owners,” he tells Wired’s Will Knight.

Stålenhag’s style was recently used to create images on the text-to-image AI Midjourney by academic Andres Guadamuz in an apparent attempt to draw attention to the legal issues surrounding AI-generated art.

Stålenhag was not amused. In a series of posts on Twitter, he said that while borrowing from other artists is a “cornerstone of a living, artistic culture,” he dislikes AI art because “it reveals that that kind of derivative, generated goo is what our new tech lords are hoping to feed us in their vision of the future.”

The dawn of a new era of AI art began in January 2021, when OpenAI announced DALL-E, a program that used recent improvements in machine learning to generate simple images from a string of text.

In April this year, the company announced DALL-E 2, which can generate photos, illustrations, and paintings that look like they were produced by human artists. This July, OpenAI announced that DALL-E would be made available to anyone to use and said that images could be used for commercial purposes.

“As access to AI art generators begins to widen, more artists are raising questions about their capability to mimic the work of human creators,” Knight says.

Digital artist David OReilly, for instance, tells Knight that the idea of using AI tools that feed on past work to create new works that make money feels wrong. “They don’t own any of the material they reconstitute,” he says. “It would be like Google Images charging money.”

But it’s not clear if the legal framework is strong enough to protect an artist’s work from AI-generated imitation.

In a blog post, Guadamuz argued that lawsuits claiming infringement are unlikely to succeed, because while a piece of art may be protected by copyright, an artistic style cannot.

READ MORE: Copyright infringement in artificial intelligence art (TechnoLlama)

Lawyer Bradford Newman tells Knight, “I could see litigation arising from the artist who says ‘I didn’t give you permission to train your algorithm on my art.’ It is a completely open question as to who would win such a case.”

In a statement to Wired, OpenAI defended DALL-E 2, saying that the company had sought feedback from artists during the tool’s development.

“Copyright law has adapted to new technology in the past and will need to do the same with AI-generated content,” the statement said. “We continue to seek artists’ perspectives and look forward to working with them and policymakers to help protect the rights of creators.”

EXPLORING ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE:

With nearly half of all media and media tech companies incorporating Artificial Intelligence into their operations or product lines, AI and machine learning tools are rapidly transforming content creation, delivery and consumption. Find out what you need to know with these essential insights curated from the NAB Amplify archives:

- This Will Be Your 2032: Quantum Sensors, AI With Feeling, and Life Beyond Glass

- Learn How Data, AI and Automation Will Shape Your Future

- Where Are We With AI and ML in M&E?

- How Creativity and Data Are a Match Made in Hollywood/Heaven

- How to Process the Difference Between AI and Machine Learning

Painted art, like motion pictures or literature, evolves and builds upon everything and everyone that has gone before it. Imitation could be homage or pastiche. Brian de Palma’s work, including Body Double and Dressed to Kill, was heavily influenced by Alfred Hitchcock. Hitchcock’s film Psycho has been recreated shot-for-shot by Gus Van Sant, in color. The infamous shower scene in Psycho is credited to Hitch, but may have been designed by Saul Bass. There is no clear line between imitation as flattery and straight out plagiarism.

As AI gets more and more sophisticated to produce longer-form narrative video, including deep fake or CG actors, the dividing lines will increasingly blur.

Short film The Crow shows just how far text-to-video has come.

READ MORE: AI Film Heralds Advance of Text-to-Video Generation (NAB Amplify)

One worry for Hollywood is that while AIs might make certain types of production cheaper to churn out, the same technology could easily be in the hands of anyone. DALL-E 2 and Midjourney, for example, are simple enough to operate by just typing (or saying) a series of simple words.

On the other hand, there is an argument that AI art should not be given the same equivalence as art generated by a human. It should matter, the argument goes, that a piece of content pertaining to mean something has been created by people who have actually lived the experience.

If AI video is inevitable perhaps the AI owner, the AI prompters, and all of the AI’s data-set training wheels should be credited in the titles?

Both Sides of the AI Art Debate

READ MORE: AI Creating ‘Art’ Is An Ethical And Copyright Nightmare (Kotaku)

There’s been a lot of debate about AI art recently, so let’s cut through the noise and provide a primer.

Leaning on a literate, well-informed piece written by Luke Plunkett for Kotaku, we’ll establish why we’re talking about AI art, provide arguments for and against, and end with the philosophical case about art itself.

Why Are We Talking About AI Art?

Algorithms have been used to generate art for decades, but a new era of AI art began in January 2021, when AI development company OpenAI announced DALL-E, a program that used recent improvements in machine learning to generate simple images from a string of text.

In April this year, the company announced DALL-E 2, which can generate photos, illustrations, and paintings that look like they were produced by human artists. This past July, OpenAI announced that DALL-E would be made available to anyone to use and said that images could be used for commercial purposes. Similar text-to-image models include Midjourney and Stable Diffusion.

READ MORE: DALL·E Now Available in Beta (OpenAI)

Basically, we now live in a world where machines have been fed millions upon millions of pieces of human endeavor and are now using the cumulative data they’ve amassed to create their own works. It has also created an ethical and copyright black hole, where everyone from artists to lawyers to engineers have very strong opinions on what this all means, for their jobs and for the nature of art itself.

The Negatives of AI Art

There are two main concerns, and both are a potential threat to the creator economy. One is that AI will automate the job of an artist (also any creative in the arts working in video games, film, and TV). The other is the aforementioned copyright black hole.

The fear expressed by artists, often anonymously to Kotaku, is that of the small-scale content creator or an artist just starting out — those who will be most affected by an AI blunting or stunting their headway in the career.

“The endgame of a potential employer is not to make my job easier, it’s to replace me,” one game designer tells Plunkett. “Or to reduce all my years spent honing my craft into a boring-ass machine learning pilot, where I’m trained to vaguely direct an equivalent software in hundreds of different directions until by chance it spits out an asset we could feasibly use in a game.”

Going on the record is RJ Palmer, who has worked for Ubisoft and on the film Detective Pikachu. He envisions a scenario where using AI a single artist or art director could take the place of 5-10 entry level artists.

“The tech is fairly basic (but still impressive) right now but it’s advancing so fast. The unfortunate reality of this industry is that speed is favored over quality so often that a cleaned up, ‘good enough’ AI-generated image could suffice for a lot of needs.”

As it stands today, AI models still requires professional artists to fix the errors it generates.

“However, it does yield results that will be ‘good enough’ for some, especially those less careful companies who offer lower wages for creative work,” Karla Ortiz, who has worked for Ubisoft, Marvel and HBO, tells Kotaku. “Because the end result is ‘good enough’, I think we could see a lot of loss of entry-level and less visible jobs.”

This would affect illustrators, photographers, graphic designers, models, pretty much any job that requires visuals — all potentially outsourced to AI.

Media websites like The Atlantic have already been spotted using AI-generated artwork at the top of articles, a space normally reserved for photos (taken by humans and paid for) or artwork (made by humans and paid for), according to Plunkett.

“We should not restrict the definition of art; we should expand it. Art doesn’t even need to have a physical form — it can be completely immaterial. What matters is the decisions the artist makes, how the public interacts with it, and what it means to the community and culture from which it springs.”

— Amelia Winger-Bearskin

There is the fear being voiced that tech giants and major publishers are only too happy to make use of AI art because they can cut costs and time by not paying a human author/illustrator for a bespoke image.

“If a large company sees an image or an idea that can be useful to them, they just have to enter it into the system and obtain mimetic results in seconds, they will not need to pay the artist for that image,” says artist Jon Juárez, who has worked for Netflix. “These platforms are washing machines of intellectual property.”

He continues, “Intellectual property will no longer have value for small authors, because you will not be able to make a Star Wars movie, but Disney will be able to use your work for their movie. If AI ends up being an Aleph of narratives, the Aleph is going to be privatized and shielded by patents.”

Calling them a “washing machine of intellectual property” is definitely one way of putting the legal concerns surrounding these art generators. Simply put, as we often see with technology that has advanced faster than the law can keep up, there is no definitive, binding stance on the copyright issues at the heart of machines chewing up human art then spitting out artificial compilations of what they’ve learned.

Kotaku reports that, last February, the US Copyright Office refused to grant a copyright for a piece of art made by an AI, saying that “human authorship is a prerequisite to copyright protection.”

However, that case is now being appealed to a federal court because the AI’s creator thinks that, having programmed the machine, he should be able to claim copyright over the works it produces.

READ MORE: Art Created By Artificial Intelligence Can’t Be Copyrighted, US Agency Rules (dot.LA)

Could it even be that AI programs are designed to actually remove tell-tale artist signatures and other identifying marks that can circumvent intellectual property?

A Practical Tool

However strongly held these arguments are, there is another side worth hearing. Plunkett quotes several artists who are dismissive of the “AI as plagiarist” charge — because, after all, the history of art and the working practices of the art world function this way regardless.

“People steal our art all the time,” says one artist. “I don’t know how many client meetings I’ve been in where they show me some artist-I-know’s work and say ‘Make it like that.’ ”

Floris Didden, art director at Emmy Award-winning design studio Karakter, which was responsible for visual development for Game of Thrones, tells Plunkett something similar:

“We all look at each other’s work for inspiration on style, execution, ideas, subjects, etc., and mixing it with our own ideas in some way to hopefully create something that can stand on its own. To my mind the programmer is doing the same thing through the use of the AI they created. I’m not saying there’s no originality but let’s not pretend we don’t massively feed off each other.”

Not everything about AI art is an ethical and copyright battleground, though. For all the discourse surrounding their creation (and creations), the machines spitting these images out are themselves mere tools, and in the right hands, tools can be useful.

“There are tremendous benefits to the tech for artists as well, which is part of why it’s such a headache,” Palmer says. “In the same way that a non-artist can now create an image, an artist can too which can be fine-tuned and enhanced through their sensibilities and training.”

Ortiz is equally enthused — and conflicted — by the practical possibilities for artists. “What if I wish to paint an object in a particular light scheme, or require a specific texture in a specific shape? AI would be an invaluable tool to assist me in my artworks! For some artists, AI would be an absolute game-changer, allowing them to have nearly immediate references to further inspire and potentially inform.”

Didden can also see the practical problem-solving benefit. “I always thought that as a concept artist you basically just needed problem-solving skills, some way to visualize your solution, and a dose of good taste (whatever that is),” he says. “So, for a designer, I think AI-generated art is going to be just another tool to use.”

Division of Labor and Nature of Art

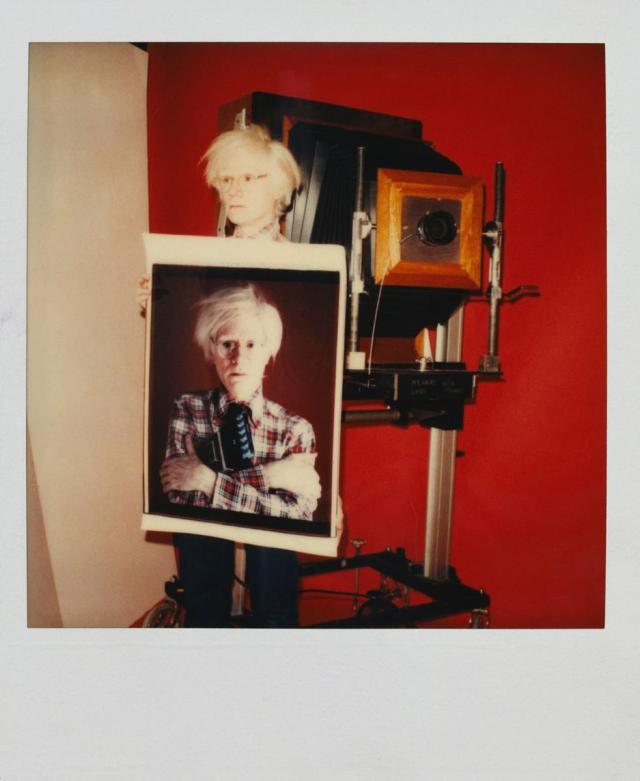

Andy Warhol, whose narration was recently voiced by AI for the Netflix documentary The Andy Warhol Diaries, famously pointed out the industrialization of art. AI is an extension of this, albeit on a massive scale. There is a legitimate concern though that artists are being ripped out of the financial equation.

READ MORE: Pop Will Eat Itself: The Ultimate Manufactured Warhol (NAB Amplify)

“Stable Diffusion is planning to make profit out of ‘private’ models for customers, profiting from creating general infrastructure layer, and currently some of their lead developers are utilizing AI generated imagery for sale,” Ortiz tells Kotaku.

DALL-E and Midjourney also have subscription models.

“Some of these companies’ current and potential profits are directly linked, via obscure data sets, to hundreds and thousands of copyrighted creative works from all kinds of creative professionals,” Ortiz adds.

“That alone is chilling, but to also have no way to opt out of these tools–especially once your work has been used to train an AI — concerns me as an artist very much.”

“I always thought that as a concept artist you basically just needed problem-solving skills, some way to visualize your solution, and a dose of good taste (whatever that is). So, for a designer, I think AI-generated art is going to be just another tool to use.”

— Floris Didden

Plunkett astutely points out that at the heart of this entire conundrum looms the false equivalency of even calling what an AI generates “art.”

“Art is inherently human,” he says. “Its ability to draw upon and inspire our emotions is perhaps the most defining thing that separates us from other animals.”

He rationalizes that a machine is not creating art. A machine, however advanced, is crunching data. “There is no perspective to AI art, no inspiration, nothing it is trying to communicate. It’s a compilation playlist built by an algorithm, spinning an endless number of remixes and cover songs.”

The counter to this is put well in a post on Medium by Amelia Winger-Bearskin: “AI-generated art is art. Of course, it is. It follows a recipe and has inputs and outputs. Developing the recipe is art, and using the recipe to bring something new into the world is also art. They’re both art,” she writes.

“Artists have been probing these same questions for at least a century now. The consensus seems to be: we should not restrict the definition of art; we should expand it.

“Art doesn’t even need to have a physical form — it can be completely immaterial,” Winger-Bearskin continues. “What matters is the decisions the artist makes, how the public interacts with it, and what it means to the community and culture from which it springs.”

READ MORE: Is AI Art Real Art? (Amelia Winger-Bearskin)

Plunkett is undeterred. The fact that so many people are getting bogged down comparing AI art to the creations of human beings, “as though the former is doing anything but adhering to an algorithm,” is playing right into the hands of those championing this mimicry, he says.

“Because it sets AI creations on a level playing field that they don’t deserve.”

There’s no right answer to this — and perhaps, like Oritz says, all we can hope for “is that the law will move quickly to protect creative livelihoods, while simultaneously allowing for these new technologies to grow in a way that is beneficial to all, not just a handful of companies and developers.”