Sampling isn’t about “hijacking nostalgia wholesale,” said DJ and music producer Mark Ronson in his influential 2014 TED Talk. It’s about inserting yourself into the narrative of a song while also pushing that story forward.

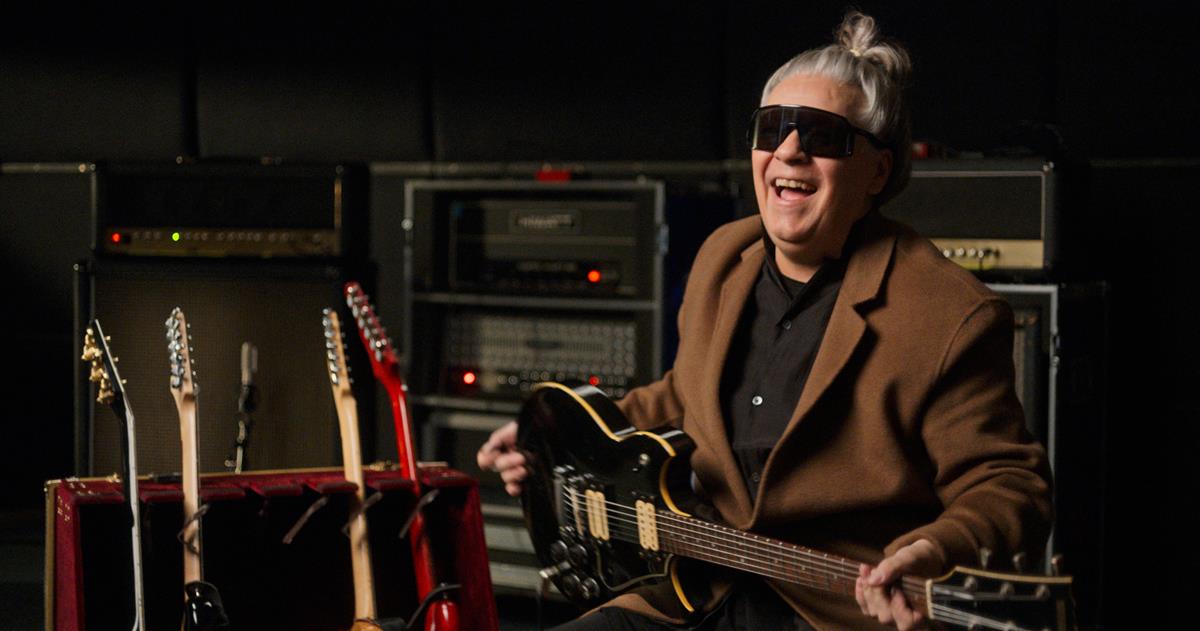

No one knows more about the evolution of sampling than Ronson and his enthusiasm for the way sounds can be crafted into hit tunes was part of the inspiration for the new Apple+ documentary series, Watch the Sound with Mark Ronson.

The other part of the equation came from Sonic Highways, the 2014 HBO documentary miniseries directed by Foo Fighters’ Dave Grohl and written by Mark Monroe about the making of the band’s eighth album.

“The initial idea for Watch the Sound was sparked by a conversation between Mark Ronson and executive producer Kim Rozenfeld,” says Monroe, an EP and director on the Apple+ show. “In turn Kim told me he was influenced by Sonic Highways in that it gave audiences a peak behind the curtain of the music world. Sonic Highways gave insight into how the physical geography of studios and locations impacted on sound. We loved the idea of making a series about how specific sounds where made, where they came from and what led to that being recorded in that way.”

Together with Academy Award-winning producer Morgan Neville (20 Feet from Stardom) of LA-based Tremolo Productions, Monroe began brainstorming what the show could be.

“Initially our idea was to select unique sounds and ask where they originate from. An example might be Prince’s snare drum on ‘When Doves Cry,’ which is not what you’d normally expect to hear from an acoustic instrument. Then, of course, Mark is a busy guy. We didn’t know how much he would want to be involved or physically where he’d be.”

Luckily, Ronson was all in and based on his desire they settled on focusing each episode around specific technology and techniques including reverb, synth, autotune, drum machines, sampling and distortion.

“We had a white board with half a dozen ideas filled with potential songs and collaborators and experts. It was pretty fast moving.”

When it came to contacting A-list contributors, “I know some and Morgan has some contacts,” says Monroe, “but everyone knows Mark Ronson. He is highly regarded. I don’t recall anyone saying no other than for a scheduling clash. For the most part it was Mark making a call.”

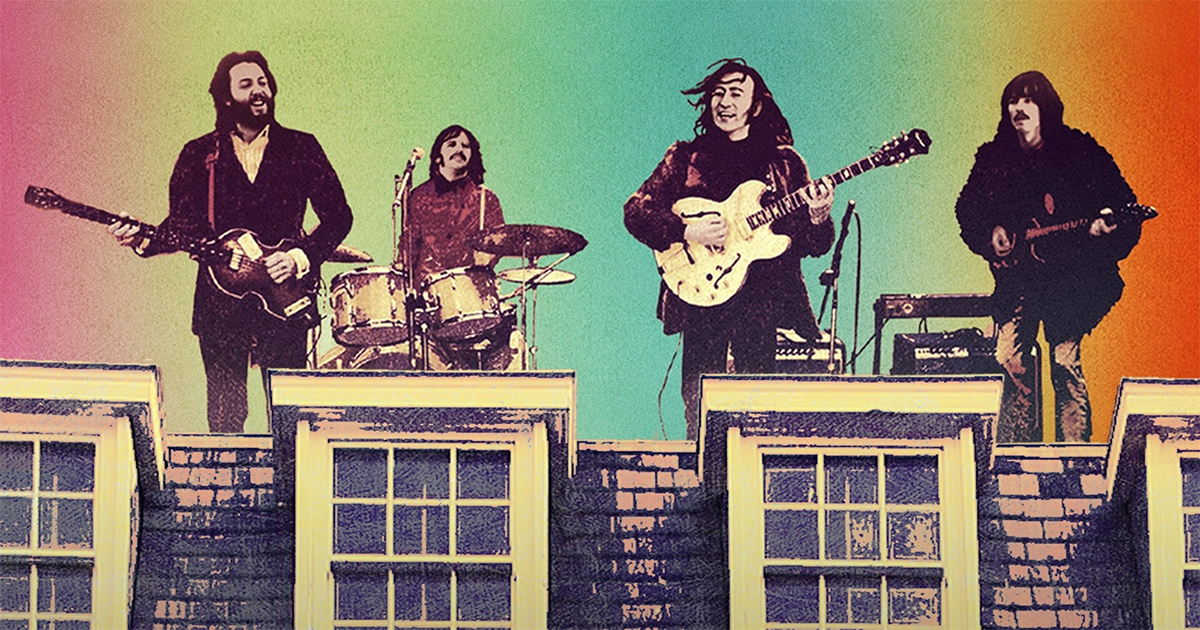

As The Guardian puts it, “the access to stars here is borderline ridiculous: there’s Dave Grohl, talking about drum machines, Josh Homme on distortion, Questlove and the Beastie Boys discussing sampling, Gary Numan dissecting synths, Paul McCartney covering, well, everything, because he’s Paul McCartney. At one point, McCartney suggests that John Lennon would have been “all over” Auto-Tune technology. Cut to Ronson in the studio with Lennon’s son, Sean Ono Lennon, as they put Lennon Sr’s song Hold On through various plug-ins to see what it might sound like.”

READ MORE: Watch the Sound with Mark Ronson review – Paul McCartney and more geek out in the studio (The Guardian)

Production began in fall of 2019 and was about half complete when the Covid pandemic threatened to derail the enterprise.

“We had time blocked out in everyone’s schedule and were a long way down the road with a style of making the show when we had to stop everything for several months. In some ways it was refreshing since it allowed us to edit some sequences to see what worked and what we had.

NOT WHODUNNIT, BUT HOW-DUNNIT — DIGGING INTO DOCUMENTARIES:

Documentary filmmakers are unleashing cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence and virtual reality to bring their projects to life. Gain insights into the making of these groundbreaking projects with these articles extracted from the NAB Amplify archives:

- Crossing the Line: How the “Roadrunner” Documentary Created an Ethics Firestorm

- I’ll Be Your Mirror: Reflection and Refraction in “The Velvet Underground”

- “Navalny:” When Your Documentary Ends Up As a Spy Thriller

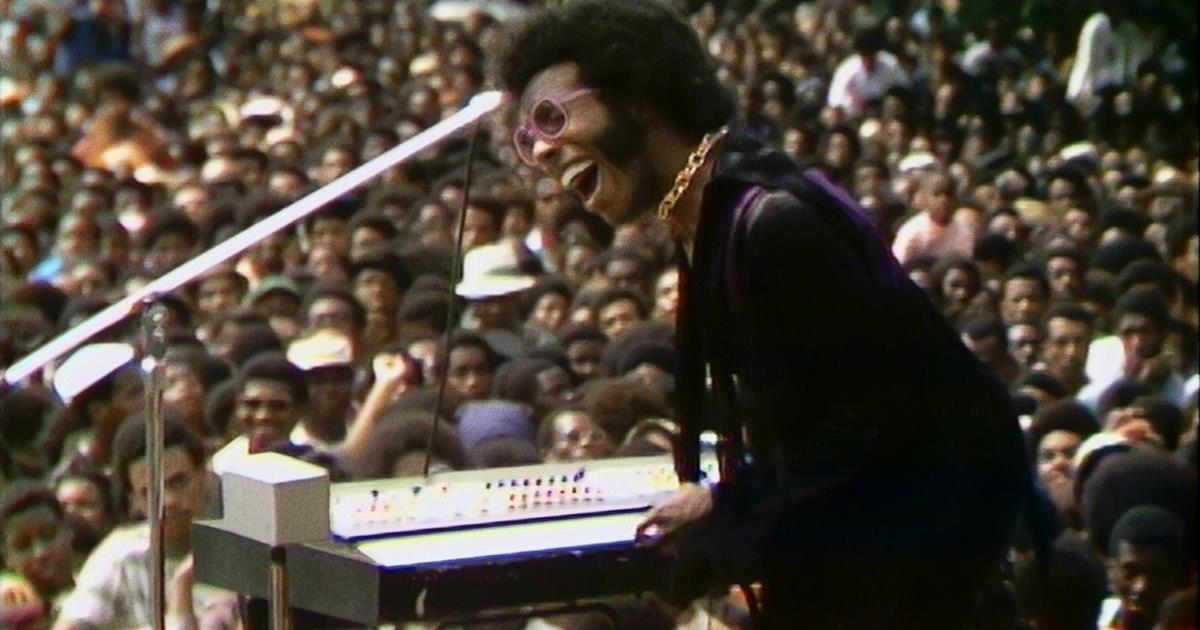

- Restored and Reborn: “Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)”

- It WAS a Long and Winding Road: Producing Peter Jackson’s Epic Documentary “The Beatles: Get Back”

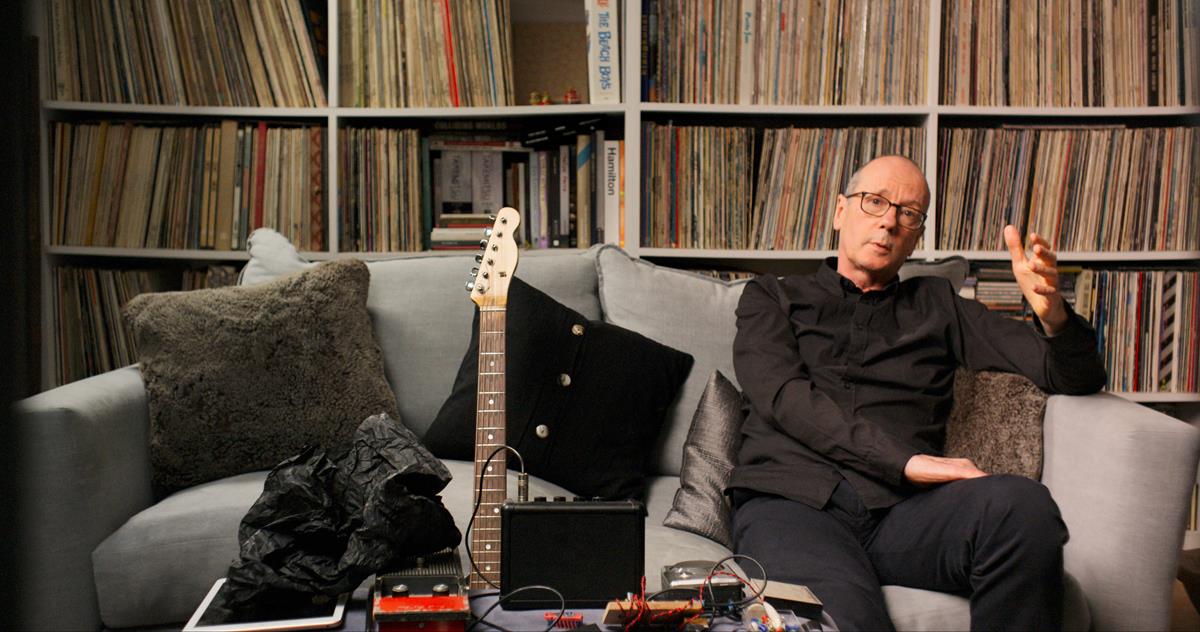

“When production resumed we made a couple of interviews by Zoom and these are in the show. We didn’t want to hide that fact. We were able to record some material without sending a crew since Mark had a camera in his studio and we had another camera on a subject in another studio.”

At the end of each episode, Ronson creates a piece of original music using techniques from the show. For example, in the episode about synthesizers, “Sir Paul is playing around on a Moog and they record it so by the end of ep you are hearing a new riff, which Mark has pulled together from things he has heard.”

Lighting and Camera Work

The show had four DPs (Mark Schwartzbard, Nathan Salter, Catherine Goldschmidt and Graham Willoughby). Given the nature of scheduling talent, compounded by Covid, they tended to work on the project a few days at a time spread out over months.

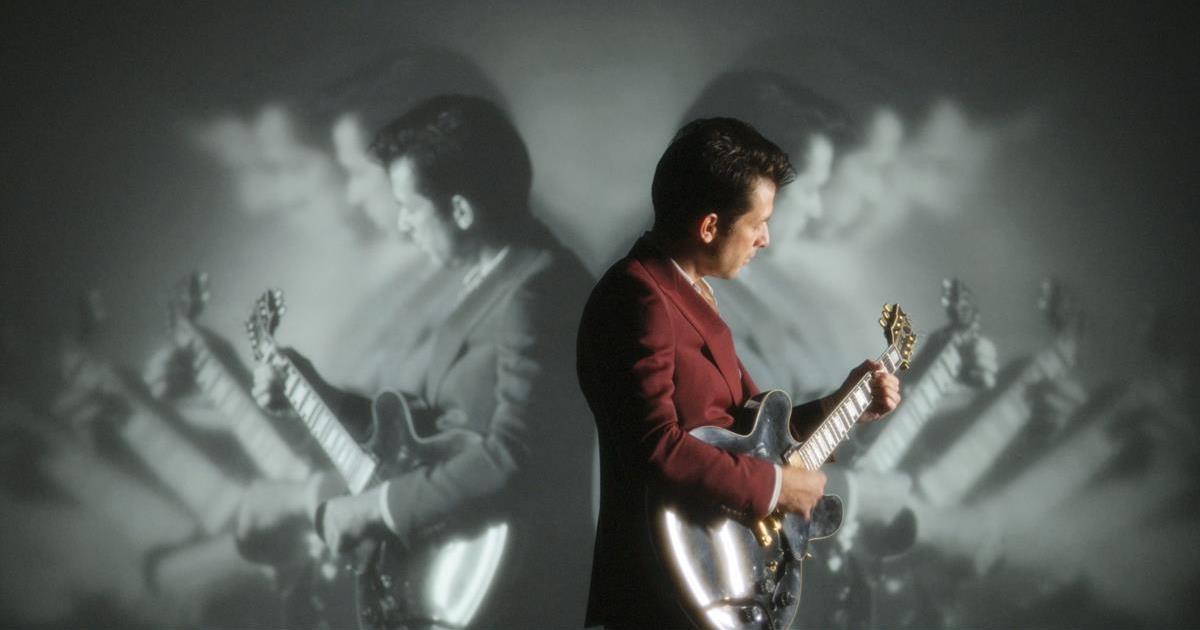

The first shoot Schwartzbard did was a big studio day of elaborate setups, including a big white void, rear projection, front projection, and a depth camera to record 3D information.

“For that day we had a sizable lighting crew and package,” he says. “Other days, shooting in recording studios, it would be one guy and a handful of lights. Personally, I used a lot of tubes on this one; quasar LED tubes and Astera Titans. Recording studio control rooms are small and have a lot of glass that reflects everything, and if you’re shooting a couple people talking and working in rooms surrounded by machines you want to give them freedom to move around wherever they’ll need to go. Taping or clipping low-profile battery operated LED tubes overhead ends up making a lot of sense.”

Schwartzbard also shot a circle of synthesizers in the big studio at A&M where Live Aid’s “We Are the World” was recorded. He explains, “We had a little bit of time and a bit of crew and equipment left over from the studio shoot the day before, so we were able to goalpost a couple Skypanels way up high and push them through an overhead 12×12 silk with a grid on it for a nice big soft overhead light. But then most of that footage got treated to look like it was on a VHS tape playing through a poorly maintained machine. We even rephotographed it off an old TV.”

Watching the Sound was shot at 4K on the Sony Venice with Cooke Panchro primes as the main lenses supplemented by older Angenieux 25-250 T/3.9s cinema zooms.

“They have a very soft, groovy, vintage look although a lot of DPs hate them,” Schwartzbard says. “They’re also small and light enough to use with documentary-sized tripods.”

He adds, “The producers were very good at scheduling things so we had adequate time to set things up and be ready by the time talent arrived. But you have to set things up wisely, so once they show up you can move quickly and be ready to follow whatever happens. As it happens, a show about music tends to spend a lot of time in recording studios, and they tend to have a somewhat consistent look, so there’s some continuity there.

“These projects are shot with many different crews working around the world, and in my experience the brief is usually: make it look cool. Respond to the environment and be willing to try things and push things. The overall look ends up being something of a pastiche of styles, which, especially in concert with various archival footage, fits a subject like this really well.”