The first thing you should know about Universal’s hit horror film Candyman is that it was directed by Nia DaCosta. Not Jordan Peele, as the studio’s marketing campaign may have led you to believe. The second thing you should know about the movie, which DaCosta co-wrote alongside Peele and Win Rosenfeld, is that it broke box office records in late August, as Tom Brueggemann reported at IndieWire, bringing in $23.3 million for its debut weekend to become the first #1 film directed by a black woman.

READ MORE: ‘Candyman’ Grosses $22.3 Million to Become the First #1 Film Directed by a Black Woman (IndieWire)

But DaCosta’s achievement isn’t being shouted from the rooftops, Tambay Obenson, also at IndieWire, complains. “As an award-winning filmmaker credited with crafting a new genre of socially conscious horror films, it’s unsurprising that Peele is a major marketing hook,” she writes, noting that the film’s official logline begins with “Oscar winner Jordan Peele unleashes a fresh take on the blood-chilling urban legend: Candyman,” a move that “created market confusion over who directed the film, which had the effect of erasing the woman who did the work.”

Ava DuVernay became the first Black woman to direct a $100 million feature in 2016 with Disney’s Wrinkle in Time, but remained an outlier for many years, as Obenson notes:

“DaCosta joined that club when Universal hired her for Candyman, but the achievement didn’t receive much attention. One possible reason: The job also brought her into a league of indie film directors tapped to make their first studio films under a major-league mentor. That enrollment represented an achievement in its own right, since the group is comprised almost entirely of white men, but also made it less likely that her own identity would earn attention.”

READ MORE: ‘Candyman’ Grosses $22.3 Million to Become the First #1 Film Directed by a Black Woman (IndieWire)

Currently rated 84% fresh on Rotten Tomatoes, the reviews for Candyman have been overwhelmingly positive. The Motion Picture Association website, The Credits, rounded up some of the bigger reviews, beginning with Manohla Dargis at The New York Times: “It’s easy to shock viewers with splatter but the old gut-and-run gets awfully boring awfully fast. Far better is the slow creep, the horror that teases and then threatens,” she writes.

Megan Navarro at Bloody Disgusting calls the film “an ambitious and haunting reclamation realized by DaCosta’s bold vision, blending horrors real and supernatural.”

“From the opening moments of Nia DaCosta’s gory yet strikingly beautiful and socially relevant Candyman, it’s clear we’re in for an especially haunting and just plain entertaining thrill ride,” Richard Roeper says in the Chicago Sun-Times.

Owen Gleiberman, at Variety, compares the film to vintage De Palma: “One reason this Candyman never feels like a formula slasher film, even during the murders, is that DaCosta stages them with a spurting operatic dread that evokes the grandiloquent sadism of mid-period De Palma.”

David Sexton, writing for New Statesmen, opines that “Candyman is quite a showreel for [director Nia DaCosta’s] talents, making brilliant use of inversion and reflection throughout. Together, Peele and DaCosta have made a definitive Black Lives Matter horror.”

David Rooney, at The Hollywood Reporter, reassures readers that Candyman’s wokeness won’t get in the way of enjoying the main event: “The attention to race, police brutality, community displacement and related issues doesn’t mean the thrills are any less spine-tingling or the bloodletting less ghastly.”

Slant Magazine’s Keith Watson writes that “Candyman doesn’t merely note the connection between fear and remembrance, it also interrogates it from every possible angle.”

READ MORE: “Candyman” Review Round-Up: Searing, Strikingly Beautiful, & Savage (The Credits)

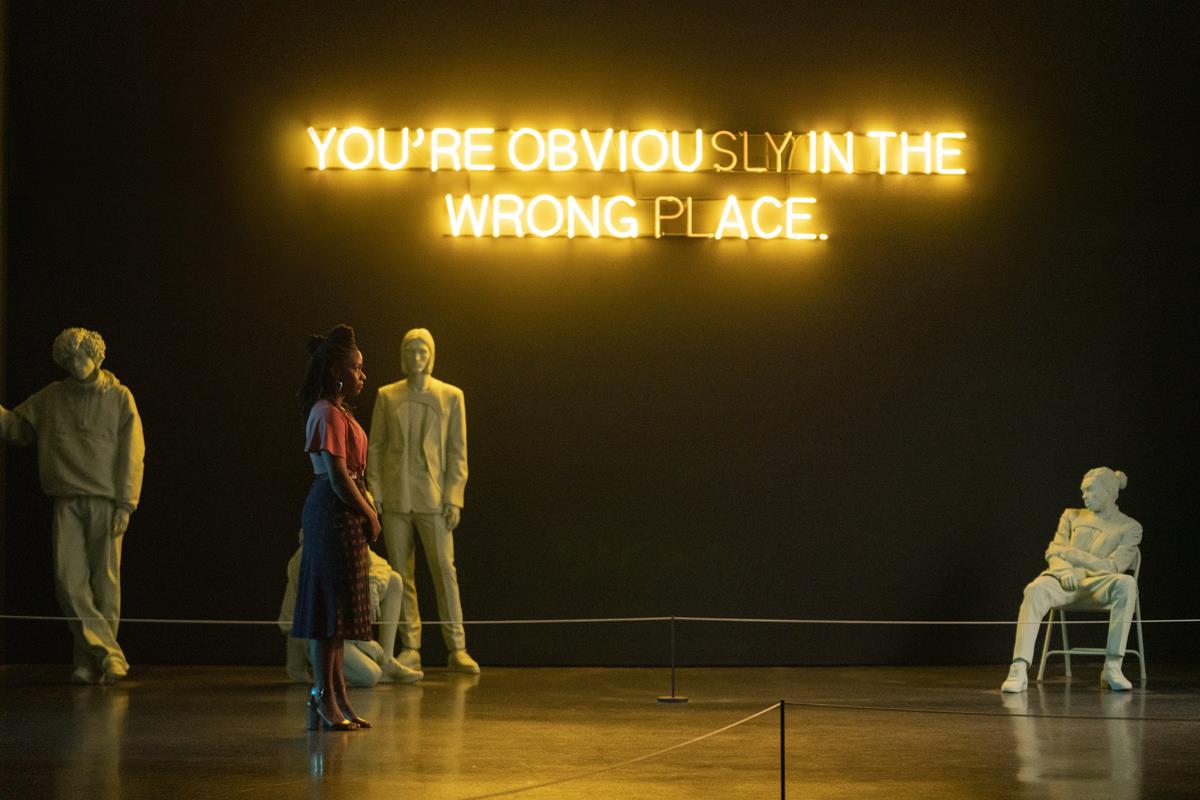

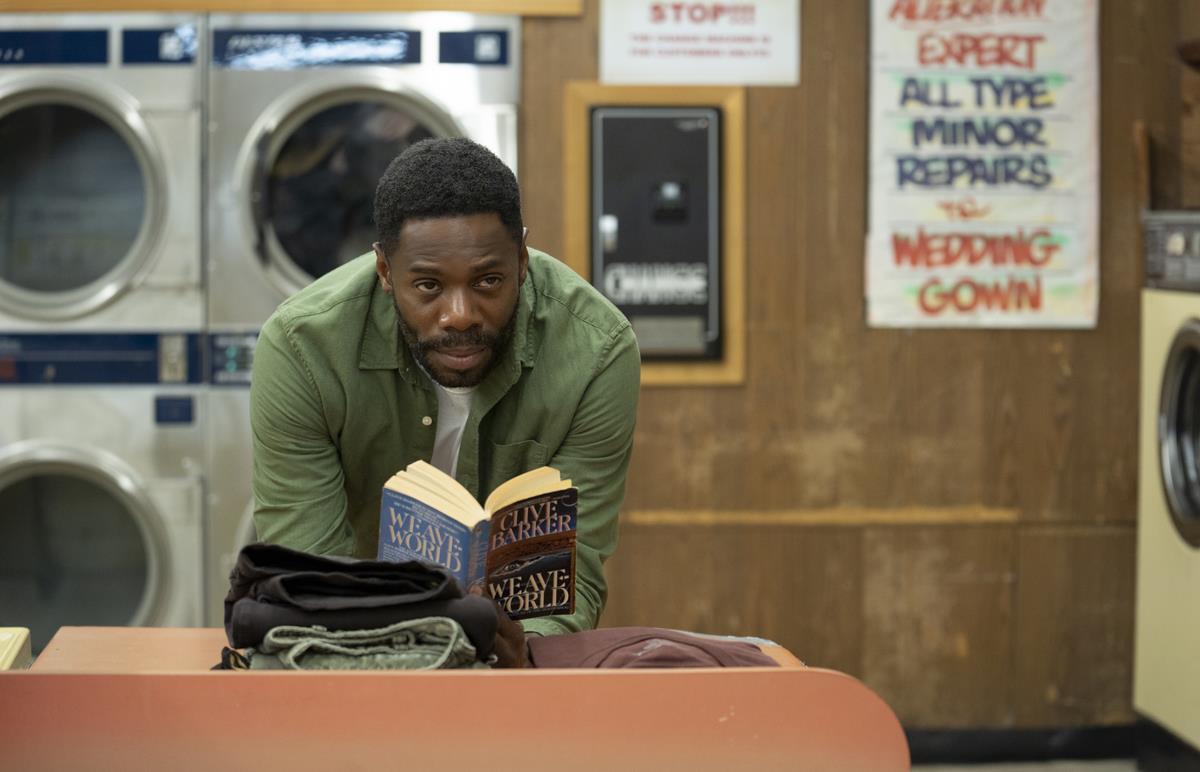

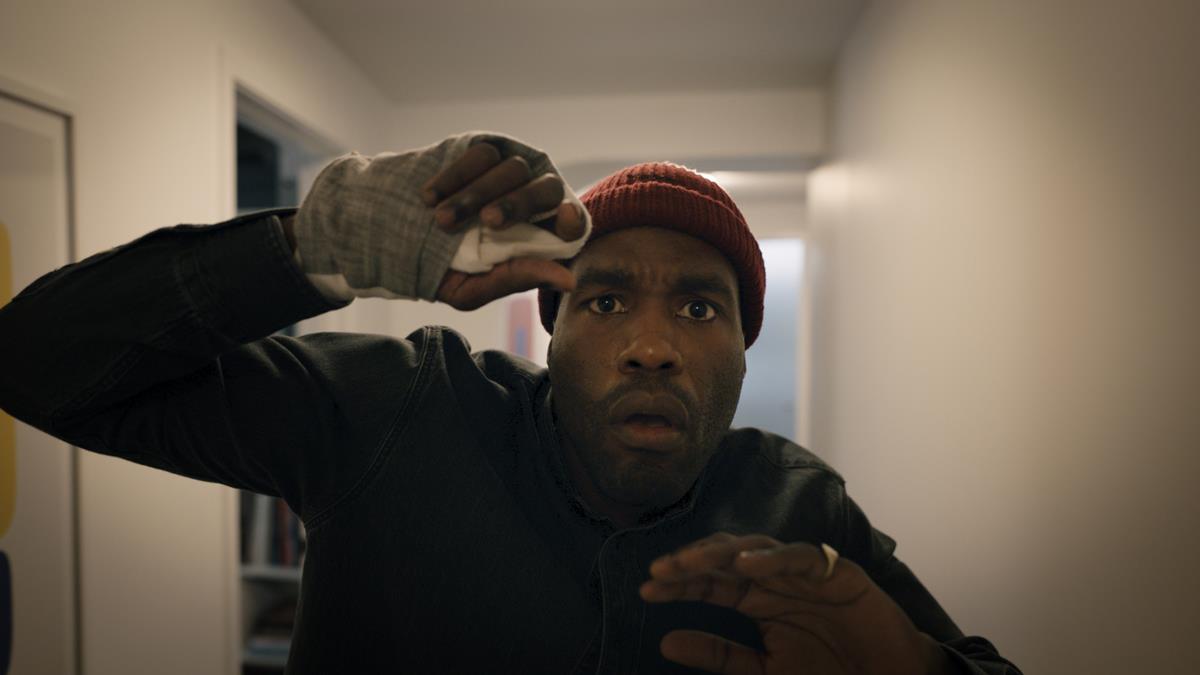

Candyman is set in present-day Chicago, following visual artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II; HBO’s Watchmen, Us) and his gallerist girlfriend Brianna Cartwright (Teyonah Parris; If Beale Street Could Talk, The Photograph). The couple lives in a luxury loft in a gentrified area that was formerly the site of the housing projects of Chicago’s Cabrini Green neighborhood, where — as legend has it — residents had been terrorized by a word-of-mouth ghost story about a supernatural killer with a hook for a hand.

With Anthony’s painting career on the brink of stalling, a chance encounter with a Cabrini Green old-timer (Colman Domingo) exposes him to the tragically horrific true story that lies behind the legend. Anxious to maintain his status in the Chicago art world, Anthony begins to explore the macabre story in a series of new paintings, unknowingly opening a door to a complex past that unravels his own sanity and unleashes a terrifying wave of violence.

David Sims, in his review for The Atlantic, recalls his affection for the original 1982 Candyman, which was directed by Bernard Rose and starred Virginia Madsen, calling it “a slasher movie rife with gore but rich with metaphor.” DaCosta “zeroes in on” the notion of Candyman’s tragic history as the source of his power, Sims writes:

Anthony’s fascination develops into a sort of appropriation, as he turns the Candyman stories into a series of frightening artworks that evoke the trauma visited on Black men for generations.

READ MORE: The Candyman Lives On (The Atlantic)

Candyman, Evan F. Moore writes in the Chicago Sun-Times, “has themes encompassing race, police brutality, gentrification, cultural appropriation and the responsibility institutions have when it comes to public housing blight.”

For her film, it was important to DaCosta to expand on the legend from the original movie. “I think it was fun to me that we shoot the POV with less Helen, but a lot more of the Black experience,” she said.

During production, DaCosta walked around the Chicago neighborhood, noticing that a Target now sits on the land where the sprawling housing project once stood. “You’d see yuppies walking their dogs, and then a little further up a Target,” she said. “It is really interesting the amount of development that’s happened around the community that didn’t seem to be able to get into the community, which is part of what the movie is about.

“I think it informs why we knew it was imperative that we expand this beyond ‘Oh, this is one sort of evil demonic killer and his story happens in the 1800s.’ We just talked about the systemic issues. … It’s cyclical and every generation we have this violence, and it changes and it warps, and it shifts so it looks differently. It’s all part of our history. So it definitely informed why we said, ‘OK, we’re going to take this “Candyman” legend and make it work for us a little bit more.’ ”

READ MORE: New ‘Candyman’ director Nia DaCosta promises a version with ‘a lot more of the Black experience’ (Chicago Sun-Times)

Positioned atop the industry, DaCosta is already in production on the Captain Marvel sequel, The Marvels, which means that she’ll have an opportunity to dominate the box office once again in 2022. Candyman follows her 2018 debut feature Little Woods, a social-realist neo-western centered around two impoverished sisters in modern-day North Dakota. But DaCosta is no stranger to horror; in high school she made a short film with a big body count called The Black Girl Dies Last.

“Candyman could be seen as an ironic comment on the fact that Black artists are expected to deal with issues of Black trauma,” Steve Rose writes in The Guardian, a statement DaCosta agrees with “a hundred percent.”

She mentions a number of conversations with people who suggested that details about her childhood, in Harlem, NY, would make good movie fodder. “It’s not necessarily overtly racist, but it is shocking the way people have talked to me in my position as a director,” she tells Rose. “People who work for me. Especially on a movie like this, where Jordan was the only other person of color at the level of decision-making on the movie. And that’s unacceptable, frankly.”

DaCosta also recounted crass comments about Black hair, and a male crew member jokingly asking if she was working as a prostitute to make money on the side. “That happened to me so many times, with people who work above me, who work laterally to me, below me,” she said. “In the moment, you’re just like: ‘Push on.’ You just deal with it. But in retrospect, I will never do that again.”

READ MORE: Candyman director Nia DaCosta: ‘It is shocking the way people have talked to me’ (The Guardian)

DaCosta was struck by how the Candyman of the original film was mostly preying on his own community, she told Anthony Breznican in an interview for Vanity Fair. “In expanding the legend and creating a bigger story about racial violence as a whole, it definitely shifted us away from, you know, seeing people in the hood getting killed. Part of that was wanting to flip on its head what happened in the [1992] film,” she said.

The original Candyman was the vengeful spirit of a Black man who was tortured to death by a mob in the 1800s. Manifested in the form of Daniel Robitaille (played in both films by Tony Todd), his hand is cut off and replaced with a hook, and he is covered in honey so that he could be stung to death by bees. In DaCosta’s film, the Candyman is powered by a entire cohort of spirits of innocent Black lives that have been ended by violence. (“Say his name,” the trailer intones.)

“Candyman’s about lynching — period,” the director told Vanity Fair last year for a feature on the power of Black horror storytelling. “That’s what it’s about, that’s the core evil that brought this demon to us. It’s very standard horror storytelling. But when you’re going to talk about lynching, you can’t just say, ‘It’s a horror movie’ and move on. For me, it was really important to very carefully balance the humanity and real life with the horror and the genre.”

READ MORE: Candyman Comes For the Privileged (Vanity Fair)

DaCosta’s pitch for Candyman included homages to several horror classics, as she recounted to Jenelle Riley at Variety. “I wanted it to feel really interesting and specific visually, in the way the original film did,” she said. “Some of my references were films like The Fly for body horror and Rosemary’s Baby, which is an amazing portrait of psychological terror that also has really beautiful production design.”

In a now-deleted post on Twitter from June 17, 2020 — Juneteenth — DaCosta released the original teaser trailer for the film, which employed cut-paper shadow puppets to depict a series of heinous events, “including a young Black boy being wrongly accused of murder and sentenced to death and a lynch mob dragging a man behind a truck,” Riley writes. Alongside the teaser, DaCosta tweeted: “CANDYMAN, at the intersection of white violence and black pain, is about unwilling martyrs. The people they were, the symbols we turn them into, the monsters we are told they must have been.”

Shadow puppetry featured prominently in DaCosta’s film, which she says was a suggestion made by Peele.

“Early on, we were talking about how to tell that story without it being trite and silly or flashing back to the original movie, because none of us wanted to do that,” she recalled to Riley. “We talked about not only the look of shadow puppets but the long history of it — how it might be the first form of telling stories in an abstract way. It represents how long this history of brutality is.”

The puppetry had a very specific purpose, DaCosta revealed: “It’s a great way to show brutality — but not,” she said.

“From the beginning I was very clear about my tolerance for violence against Black people,” she added. “I love gore; I love body horror; I love all that stuff. When it’s about enhancing the psychological terror, go for it. But I didn’t want to depict what we see every day.”

READ MORE: With ‘Candyman,’ Director Nia DaCosta Puts a Killer Spin on a Horror Classic (Variety)

“The shadow puppetry in Candyman reflects how the storyteller influences the perspective of the legends we are told,” Alyssa Miller writes in No Film School:

“The conscious choice to keep the silhouette of the hand controlling the shadow puppets was to show the audience that the person telling the story is just as important as the story being told. Typically, hands and unwanted shadows would be edited out of this post, but DaCosta saw the importance of the creation and physical control of the narrative being told through the puppets.”

Discussing the shadow puppet sequences for Fandango All Access, DaCosta shared that she was also inspired to use shadow puppetry to tell the stories of the Black men and children who became a version of the Candyman after researching Kara Walker, an artist recognized for her use of cut-paper silhouettes depicting historical narratives haunted by sexuality, violence, and subjugation, and German director Lotte Reiniger, who pioneered the use of the silhouette in her films.

In the video below, DaCosta breaks down how the shadow puppet sequences affect the retelling of urban legend in a way the original Candyman failed to do so:

READ MORE: Nia DaCosta Breaks Down the Silhouette Stories from ‘Candyman’ (No Film School)

Commemorating this year’s Juneteenth — the same day the date was recognized as an official federal holiday — DaCosta released a stirring message about Black violence.

“I was thinking a lot about the duality of the Black experience, and how it relates to America,” she says in the video. “At once it’s this place of great hope, which I think is what Juneteenth represents in one way, it’s a celebration of us, of life and freedom and possibility. On the other side, it’s incredibly difficult and there’s a lot of pain and they kind of walk hand in hand. I think that’s something about this film as well, there’s still this sort of bittersweet hope.”

“The art within Candyman is definitely about devolution to mirror his psychological descent,” DaCosta says in a video featurette about the making of Candyman.

To credibly create Anthony’s increasingly dark artwork for the film, the filmmakers turned to real artists, including Arnold Kemp, Cameron Spratley, and Sherwin Ovid. “It seemed critical that there were actual artists in the film, and works that had social relevancy,” producer Ian Cooper says in the video.

Another featurette, entitled “Candyman – A Look Inside,” features producer and co-writer Jordan Peele reflecting on his fascination with urban legends, while director and co-writer Nia DaCosta discusses the timelessness of the Candyman legend.

“Candyman is so perennial,” she says in the video. “We’re talking about cycles of violence and how history repeats itself, and how we collectively process trauma through stories. It’s always time to tell a story like Candyman.”

Want more? Watch DaCosta break down a scene from Candyman in The New York Times video series, “Anatomy of a Scene.” While Anthony becomes more obsessed with the Candyman legend, his girlfriend Brianna wants to bury the legend and stop it from recurring:

You can also listen to “Candyman Gets An Update, And The Horror Is Gentrification,” on NPR:

In a VFX breakdown from Luma Pictures for Collider, VFX supervisor Andrew Zink recounts how the iconic Candyman was created using 3D modeling. Initially, the production employed an actor wearing prosthetics, but “the filmmakers decided the prosthetic wasn’t real or visceral enough” in post-production, leading Luma Pictures in a race against the clock to create a full-digital version of the character.

“It was a hard and fast pivot for us,” says Zink. “This was challenging because we didn’t receive any references of his head or face. And since Sherman [aka The Candyman] was never meant to be a full digital double, there was of course no motion capture or facial performance footage available. We had to quickly develop a complex facial-animation rig that would breathe life and nuance into his facial performance. We also researched crime scene photography, blunt force trauma wounds, and medical references in order to craft his asset with a high level of detail and ensure he would hold up to multiple close-ups.”