“It’s a big movie and a small one,” admits The Midnight Sky cinematographer Martin Rühe, a frequent collaborator of director and actor George Clooney. They’ve shot The American, Hulu’s Catch 22 and now The Midnight Sky together, Clooney directing or co-directing the last two. (He describes his working relationship with Clooney, “I think he’s a very good director, very visual. He’s a very trusting man so there’s no second guessing with him. I like it.”)

Rühe has been one of the DPs that has transcended through film to digital cinematography, experiencing all the cameras that tried their luck along the way, including the gone but not forgotten Panavision Genesis, ARRI D21 and Thomson Viper.

The film is Rühe and Clooney’s first science fiction movie and had a challenging brief: Lily Brooks-Dalton’s novel describes the potential end of the world but has isolation, despair but ultimately spiritualism at its core. Perhaps this is why Rühe sees the film, as small as the relationships between the characters are under the microscope throughout, as a counter to the expanses of space and the Arctic. (Martin also shot with some specialist lenses that the film Mulan had previously used to keep their main character front and center. More on those later.)

The shoot was 70 days in 2019 that included nearly two weeks in Iceland during their fall and a few days in Spain, but with the most time spent on sets at Shepperton Studios in the UK. The choice of camera was the Alexa 65, the biggest canvas in digital cinematography, another first for the DP.

“We had the biggest way to tell this ultimately intimate story. We go to space and are in the Arctic and see how people are really isolated, physically and mentally,” he says.

“When I thought of the big vistas of say Iceland I thought of the 65. I didn’t know too much about it but when I started testing I realized that when you shoot 65 you have to look to use wider lenses and get close to get the effect people talk about. You end up being more intimate with your people, you get so much detail and read so many things in their faces. I really love that.”

If you check Martin’s camera package for the film on IMDB you find that he used the Hasselblad lenses which, were the original glass for the camera. He did test them but didn’t like them, finding them too clean, which was the last thing he wanted on top of a digital camera. Martin ended up with the DNA range of lenses from ARRI Rental.

“We had the biggest way to tell this ultimately intimate story. We go to space and are in the Arctic and see how people are really isolated, physically and mentally.”

—CINEMATOGRAPHER MARTIN RÜHE

The DNA lenses were first used by Bradford Young on Solo: A Star Wars Story and are a mixture of old and new glass. ARRI Rental encourage their DOP customers to customize the glass, an invitation that Martin was more than happy to accept. His first act was to detune them. The range included those Mulan examples. These lenses are called “T types” and they are based on very early turn-of-the-century optical design and performance, similar to the early Voigtländer-Petzval objective lens of the late 1800s. This creates a strong center punch area of focus and more extreme focus fall-off and focus aberration towards the edge of frame that is exaggerated on an Alexa 65 sensor, due to sensor size and lens image circle.

Martin used these T Types to isolate some of the film’s characters: “If you had two people standing next to each other, you couldn’t have both in focus. We used those lenses when we wanted to get more in the head of Augustine’s character (played by Clooney) or Sully (Felicity Jones’s character). ARRI’s cameras are great, but I didn’t use their lenses as much; but in the last few years they have been listening more to DOPs. This was the second time now I’ve used ARRI lenses and really like it.”

Shooting in Iceland in their fall and on a glacier at night for two weeks with an unwieldy camera isn’t the easiest proposition but Martin saw it as “a big adventure.”

“Just to go to the location, we had to go to a base camp,” he says. “From the base camp, you put your gear into trucks or buses and then you go into a small caravan on to the ice. There are many crevices and everything changes quickly. We shot in real snow storms that you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face. So we had to be ready for certain things as it was almost impossible to plan.”

The weather forced Martin to keep his team quite small and to try to shoot as much handheld as he could, though having difficulty using a dolly when needed. With the winds they couldn’t even put up a light. But with a great history of shooting big movies out there, like Interstellar, Rogue One and Oblivion, the support from the local crews was amazing, especially when it came to safety. Even with the weather, they did manage a couple of aerial shots with a DJI Inspire drone as they didn’t want to keep a helicopter on standby for a break in the weather.

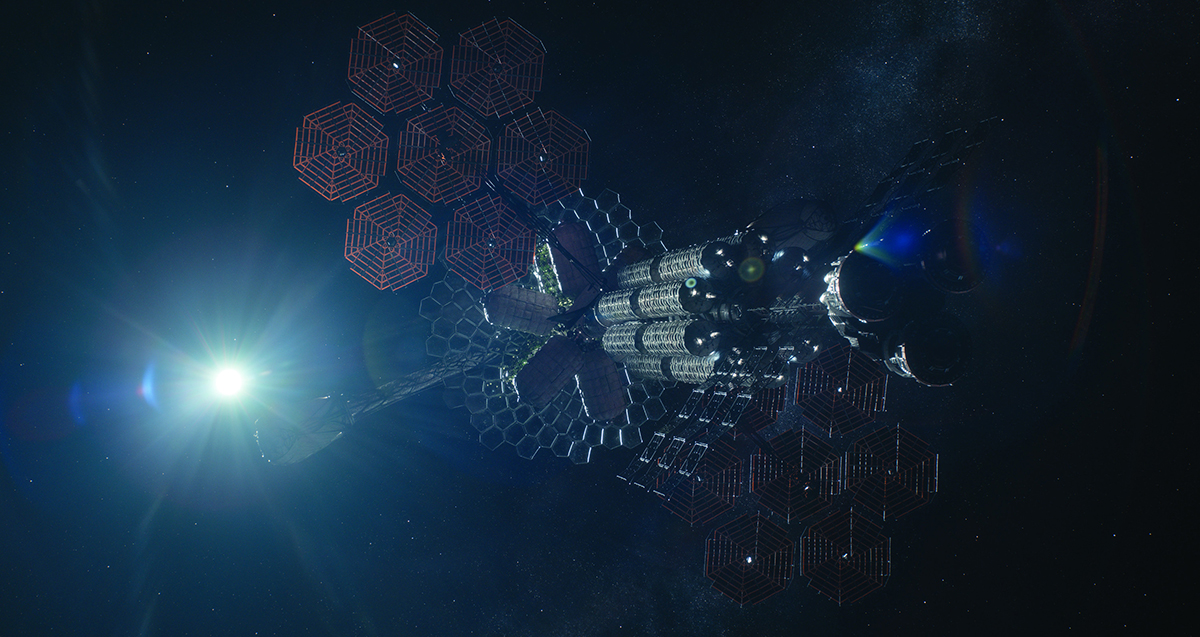

Having survived the harshness of the Icelandic pre-winter, Martin and his team headed for the main sets for the Arctic observatory, the even more remote radio listening camp and the sets of the long-range space craft, Aether, on its way back from the Jovian moons. Also, ILM’s Mandalorian LED volume was waiting for them. This type of live VFX was also new for Martin.

“We had some Iceland shots we had to finish off in Shepperton, like some snow storm scenes and some on the ice. But then we did three things that were absolutely new to me. One thing was that when we shot Barbeau Arctic station, we used the system from ILM, but we used it slightly differently. Basically, everything we see through those windows in the Arctic station was this huge LED wall which was around 120 feet by 25 feet. We sent a unit to shoot plates for that and they put a lot of cameras into our set, which were tracking our camera, so they could calibrate the background so the parallax was always right for the lens. Then you really have the feeling that you’re looking out in to the Arctic.”

Like most creatives who have experienced shooting this way, the relief from using green screen is huge and enabling. You can keep all your reflections and use them to light. Martin was keen to experiment. “You can use part of the screen that you’re not looking at to be brighter or darker. You can switch that part off and then turn it on when you pan in that direction. It emanates so much ambient light from the wall and the ceiling that under certain circumstances—a cloudy sky for example—it’s hard to define light directions. So the relationship between your practicals and the LEDs need precision to match each other but if you get that right you get realism which is amazing.”

For Martin, having this ambient light from the LED wall allowed him to measure the use of lighting rigs and maybe use them selectively for light enhancement, for say the sun or general light direction.

LED volumes are expensive and only work for single camera situations as you can’t have multiple cameras due to the parallax issues. The screen technology has come from the events business who are looking to extend their reach due to COVID-19 putting live events mostly on ice. And obviously game engines with their polygon-friendly rendering, the not-so-secret sauce that allows this real time VFX magic. For DOPs like Martin, this means finding your place amongst the production time slips which are appearing. “You need pre-production time to get your plates ready to be processed, you almost have to have layers on them using different lenses to fall-off in different ways. It’s sounds complicated but it’s really cool too.

“We also had a big space walk sequence and for that they did a rough animation of it for us. We would then shoot it virtually. We were then able to go in to a meeting room, where they had put marks on the floor, and with an iPad I was able to film it. So I put the camera in different positions and basically in that way we created a previs. We knew that we needed the ship to be a little bit longer here and there, so that gave us the potential to get more tension into the sequence by virtually shooting it. We learned, that say, this shot was full CG and this shot we have an actor in the foreground with a CG person in the background – it was really informative. Rather than making it up on the day, we knew that this was our sequence as we had it previsualized using this virtual camera.”

“Just to go to the location we had to go to a base camp. From the base camp, you put your gear into trucks or buses and then you go into a small caravan onto the ice. There are many crevices and everything changes quickly. We shot in real snow storms that you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face. So we had to be ready for certain things as it was almost impossible to plan.”

—CINEMATOGRAPHER MARTIN RÜHE

Martin was fully committed to this new way of working and hugely enjoying it, apart from one step too far for him, the use of VR goggles. “It freaks me out a little, so I took the iPad and asked the computer operator which lenses I wanted loaded. You point your iPad and then you know where you are in space, as long as you have your scale correct you know what makes sense. You find that you are getting more of a say in shots that would usually be defined by the VFX departments.”

Matt Kashmir, VFX Supervisor for the movie, had worked with Martin on HBO’s’ Catch-22 and is a regular for Clooney’s productions. With that relationship intact, it was always clear that Martin would be part of decisions for the post-production, maybe something that DOPs need to start to tie-down in future live VFX productions. “For post production this year, they were open for my input. We talked over shots about how they play out, the lighting, the design. It was great and a real mix of departments being really creative.”

It’s clear that Martin has adapted well to the new tools of virtual production with the caveat being, as long as the shot is better with the use of it. There are some shots, especially in the space walk scenes, that he acknowledges as being beautiful due to the virtual planning of them. “I like what we can do with technology these days. I like that the cameras are smaller and that you can shoot with less lighting — but you have to base what you do virtually in reality. If it doesn’t look real, then people will know.”

The Midnight Sky is streaming on Netflix from December 23.