By Adrian Pennington & Julian Mitchell

The writer-director Mike Flanagan has become best known for his adaptations of works by Shirley Jackson (The Haunting of Hill House), Henry James (The Haunting of Bly Manor) and Stephen King (Gerald’s Game, Doctor Sleep). The horrors in his latest project, Midnight Mass, a seven-episode limited series on Netflix, are homegrown.

“Flanagan has earned a reputation for what might be called humanistic horror,” writes Darryn King in The New York Times. “Beyond the ghouls and goose bumps, much of his work is centered on deeply felt family drama, populated by damaged characters wrestling with the everyday terrors of being a parent, a partner, a human being.”

The Ringer lauds him for “prioritizing characters and emotions over cheap scares and shock value.”

Screen Rant suggests that Midnight Mass “delves into a whole range of poignant themes and even perfectly depicts a universal truth at the heart of religion.”

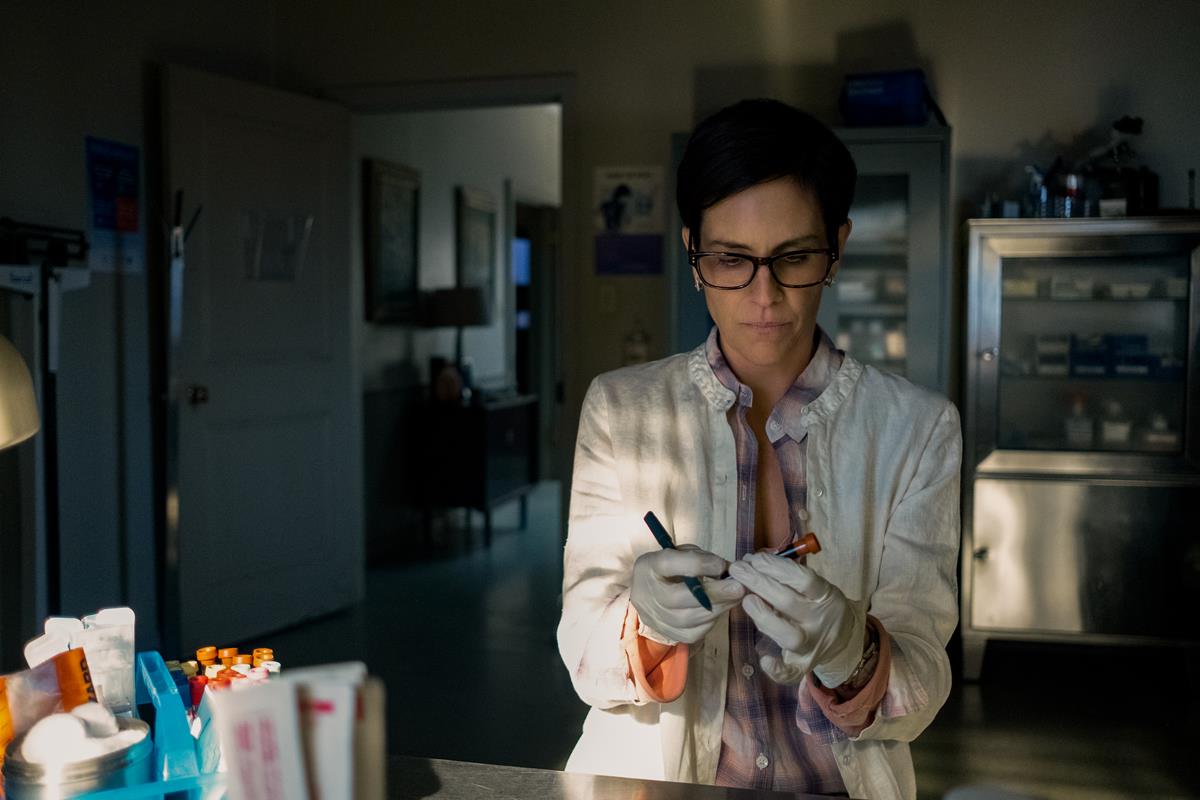

Midnight Mass is set on the fictional Crockett Island, an isolated fishing village 30 miles from an unnamed mainland, where a new Catholic priest arrives after the old one goes missing following a religious sabbatical in the Middle East. The series has the island residents fall prey to a vampire-like monster mistaken for an angel along with a renewed religious fervor. Both are unleashed upon the island by Father Paul Hill/Monsignor Pruitt (Hamish Linklater) and contribute to a tense and bloody conclusion.

Set on the fictional Crockett Island, the series has its residents fall prey to a vampire-like monster mistaken for an angel and a renewed religious fervor. Both are unleashed upon the island by Father Paul Hill/Monsignor Pruitt (Hamish Linklater) and contribute to a tense and bloody conclusion.

READ MORE: Mike Flanagan Swings for the Heavens (The Ringer)

While Hill House was a huge hit, its follow up Bly Manor was less successful but Flanagan remains a darling of the critics not least for battling his personal demons so publicly. Specifically, Midnight Mass lays bare his experiences with religion and alcohol addiction.

“I come from a long line of drunken Irishmen,” he told the NYT. “But my biggest fear wasn’t that I would die in a drunken car accident,” he continued. “It was that I would kill someone else and live. That is the beating heart of Midnight Mass.”

In a behind-the-scenes featurette, Flanagan describes Midnight Mass’s Riley Flynn (Zach Gilford), a former altar boy and a reformed drinker haunted by a drunk driving accident, as his “Avatar.”

Growing up a Catholic he says the “scales fell from his eyes” when reading the Bible, aged 12.

“There were so many ideas I’d never heard before in church, and the violence of the Old Testament God is terrifying! Slaughtering babies and drowning the earth! It really struck me that I didn’t know my faith at that point.”

READ MORE: Midnight Mass Perfectly Captures The True Spirit of Religion (Screen Rant)

Midnight Mass speaks to his continued interest in faith in its most extreme form. “I’m fascinated by how our beliefs shape how we treat each other,” he said. “Looking at politics and the world today, so many of us are behaving based on the belief that God is on our side, and that God dislikes the same people we do.”

He first pitched Midnight Mass in 2014, including to Netflix, which passed on it. Before that, it had been an unfinished film script, and before that an attempted novel. Midnight Mass even appeared as a prop book “Easter egg” in Hush and Gerald’s Game, his own way of keeping the idea alive over the years, he revealed to the Times.

Flanagan studied film at Towson University in Maryland, and spent a decade as an editor in LA while trying to get projects off the ground.

READ MORE: Mike Flanagan Explores His Private Horrors in ‘Midnight Mass’ (The New York Times)

Flanagan lets the series breathe with beautifully shot and written walk-and-talks often shot in a single take, before hell breaks out — literally. The series cinematographer was Michael Fimognari, who had previously shot Gerald’s Game, The Haunting of Hill House, and Doctor Sleep with Flanagan.

NOW STREAMING — BEHIND THE SCENES OF FAN-FAVORITE SERIES:

As the streaming wars rage on, consumers continue to be the clear winners with an abundance of series ripe for binging. See how your favorite episodics and limited series were brought to the screen with these hand-picked articles plucked from the NAB Amplify archives:

- “Severance:” Now, About Solving the Work/Life Balance…

- Entering “The Gilded Age”

- Class Is Definitely Not In Session: The Horror Delights of “All of Us Are Dead”

- “The Dropout” Is a Slow-Motion Car Crash (and We Can’t Look Away)

- The (Unavoidable) Universal Appeal of “Squid Game” Is By Design

Fimognari told Filmmaker Magazine about his shooting design for Midnight Mass. “We decided to go with the Alexa LF camera. It was the first time that we departed from the Alexa 65 in a while. We used the 65 on Gerald’s Game, Hill House and Doctor Sleep. We wanted a lighter camera for Midnight Mass, so we were willing to trade that mobility instead of having some of the extra resolution,” he said.

“The LF also allowed us to shoot with anamorphics, which wouldn’t have been an option on the 65. So it was the right combination of elements. We rated the LF’s at 1600 ISO and shot on Atlas Orion anamorphics. We wanted lenses that had a slightly ambiguous quality at the edges so that they weren’t perfect, and we wanted (lenses that were fast enough to allow) the candlelight to do some real work. We found the Atlas Orions to do both.”

Another first for Fimognari was the way camera teams were designated on Midnight Mass. Rather than camera teams A, B and C, they were classed as green, red and blue. “This was the first time that we’ve done that. It was something that I pitched to our team because there’s a thing that sometimes happens where you get caught up in the hierarchy of what the A Camera means and what the B Camera means.

“Sometimes people feel like some shots are more important than others just based on which camera is doing them, or some teams feel entitled to have the more challenging shot or the shot that is perceived to be more important based on [those letter] designations.

“I felt strongly that we needed to strip that away. On our shot list every shot matters. There’s no shot that isn’t on the page for a reason. We had some people who we considered to be part of the team who essentially opted out of the project because they cared very much about the designation on their credit. They said, “I’m only going to do it if I’m the A Operator or the A 1st.” And I explained, “Hey, I get it. You will be treated that way, but we’re not going to name it that way.” And some people said, “No thanks,” which is fine.

“That sort of served its purpose [in building the team] as well because we want everybody to feel like their shot is important, because it is, and we want everybody to feel equal on the team, because they are.”

The island took a while to scout as it needed to accent its isolation and then build the community that had experienced devastation a few years before. Fimognari talked about how they defined the island. “The first element for us was to find the right landscape. It’s an island so it can’t have those Pacific Northwest mountain views or steep hills. That ruled out quite a few environments for us. We ended up searching and searching and searching and, ultimately, we split it up into two parts.

“There was the water view, which we found in a park, and fortunately we were able to get permission to close a portion and build structures. Then there was a big plot of land that the larger portion of the town was built on — the church and the town square and everything else.

“The trick there was once again finding the right spot where you could put a camera anywhere and move it 360 degrees and have the view always be faithful to the island. We spent a lot of time there just walking those spaces and figuring out things like where the paths should go in the town. We walked out our long walk-and-talk scenes where we wanted to film unbroken shots, and we talked about things like what to make the roads out of so we didn’t hear a lot of crunching and moving while the actors were talking.

“Mike is a very specific leader. He can tell you what matters and what doesn’t and where to put your time. We have very specific shot lists — that’s really the first step for us. It’s been that way since Oculus. Then we put them down into overhead plans so that everybody can see them because Mike plans out his blocking. He really understands where he wants the characters and how he wants them to move.

“Almost all the interiors were on stage. There were a handful that required a transition shot from an exterior to an interior, but not many. The general store was one that was shot on location. There were just too many windows, and we followed people in and out of the doors, but most of the interiors were stage work.”